![]()

Chapter 1

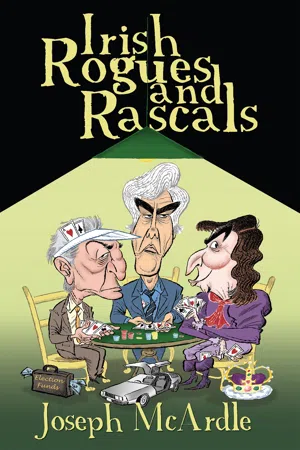

The spinning bishop: Myler Magrath

Myler Magrath was a proper rogue. One could even say that he was the quintessence of roguery, a weathervane that spun around as the wind blew. He loved women, drink and money, but not necessarily in that order. In an age when O’Neills were killing O’Donnells, Highlanders were killing Lowlanders, Tír Chonaill was raiding Connacht, and James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald and Donal McCarthy Mór were massacring English settlers, Magrath was, essentially, devoted to the quiet and civilised accumulation of capital. He was a capitalist rather than a gangster.

Nonetheless he had a theatrical streak and rode around ‘like a champion in town and country in doublet of proof buff leather, jerkin and breeches, his sword on his side, his scull and horseman staff with his man on horseback, after which a train of armed men to the great terror and bad example now in a most quiet time,’ and when there were ‘any matters of controversy with his neighbours’ he was well able to assemble ‘an army of horsemen and footmen to win his demands with strong hand.’

‘Myler’ is a corruption of Maolmhuire (devotee or servant of Mary), and Mary took care of him in spite of his behaviour. In an age when it was the rule rather than the exception that public figures should lose their heads and that the life expectancy of Catholic priests was short, Myler died in bed, a centenarian.

He was born in what is today County Fermanagh in or about 1522 to an ecclesiastical family, in the sense that his father, Donncha Magrath, was the coarb or guardian of church lands, called Termon Magrath and Termon Imogayne, in present-day Counties Fermanagh, Tyrone and Donegal. Termon Magrath was not an ordinary holding: it included St Patrick’s Purgatory on an island in Lough Derg, one of the three entrances to the Underworld and a place of pilgrimage that rivalled Santiago de Compostela in the sixteenth century and even earlier.

Myler’s eye for the main chance was inherited. When King Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries came into effect, Myler’s father obtained a grant of the local Augustinian monastery with an assurance that it would pass to his son. Many years later, when Myler had won Queen Elizabeth’s favour, he would obtain confirmation of his father’s surrender of the territory only to have it regranted to him with letters patent from the queen.

Myler entered the Franciscan order when he was eighteen and took Holy Orders in 1549. He had been fostered with several influential families, among them the powerful O’Neills, and, no doubt because of this connection, he was sent to Rome in 1565 to lobby on behalf of the brother of the great Shane O’Neill, who wanted to become Bishop of Down and Connor. Somewhere along the way Magrath decided that he himself would be a more suitable occupant of the post. He convinced the papal entourage that he was a blood relative of Shane O’Neill, Prince of Ulster, and won golden praise for recovering papal letters of credence from the Pope attesting to the consecration and granting of the archiepiscopal pallium to Richard Creagh, Archbishop of Armagh. These letters of credence had been confiscated from Creagh when, on his journey home from Rome to Ireland, he had been arrested in England and thrown into the Tower of London.

The Vatican issued him with documents stating that the ‘application and exceptional efforts’ of the new Suffragan Bishop of Down and Connor and his ‘great energy and enthusiasm’ had accomplished, through his ‘care and diligence,’ something that the papal proctor could not achieve, and Archbishop Creagh was requested to assist Magrath’s worthy efforts in his diocese, since he would be of great use in promoting the welfare of the Armagh church and its flock. It was decided that it was best that the recovered letters should be committed to the care of the ‘resourceful bishop’, who would shortly be following Creagh back to Ulster.

One wonders if John Le Carré’s George Smiley would not have wrinkled his nose at Magrath’s ability to remove valuable documents so easily from the clutches of the English secret service. Could it be that he was already playing a double game?

Unfortunately for Myler, his machinations in Rome did not generate any personal profit. Shane O’Neill was called Seán an Díomais—Seán the Proud—but díomas also means spiteful and vindictive. It is not to be wondered at, therefore, that when Myler returned to Ireland Shane took enough time off from plundering Dundalk, burning Armagh Cathedral and repulsing Sir Henry Sidney, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, to make sure that none of the revenues of the see went to the new bishop.

Certain civilities must have been observed, because Bishop Magrath accompanied Archbishop Creagh some time later when the archbishop met Shane O’Neill on the island of Inishdarrell on a lake in County Armagh.

In the following year, without formally renouncing Roman Catholicism, Myler Magrath submitted to Queen Elizabeth I and took

a corporal oath upon the evangelist that the Queen’s highness was the only supreme governor of [the] realm, and of all other her Highness dominions and countries, as well in all spiritual or ecclesiastical things or causes, as temporal, and that no foreign prince, person, prelate, state or potentate [had], or ought to have any jurisdiction, power, superiority, pre-eminence, or authority ecclesiastical or spiritual within [the] realm; and [he] utterly [renounced and forsook] all foreign jurisdictions, powers, superiorities, and authorities, and [promised] that from henceforth [he should] bear faith and true allegiance to the Queen’s Highness, her heirs and lawful successors, and to [his] power [would] assist and defend all jurisdictions, pre-eminences, privileges and authories granted or belonging to the Queen’s Highness, her heirs and successors, or united and annexed to the imperial crown of [the] realm.

Myler knew when swearing this oath that

if any archbishop, bishop, or other ecclesiastical officer or minister . . . shall peremptorily or obstinately refuse to take the said oath, that he then so refusing should forfeit and lose, only during his life, all and every ecclesiastical and spiritual promotion, benefice and office . . . which he had solely at the time of such refusal made; and that the whole title, interest, and incumbency, in every such promotion, benefice and other office . . . should clearly cease and be void, as though the party so refusing were dead,

but he went ahead and swore.

Two years later, in 1569, Magrath was seized in England and imprisoned in London, where he may have been tortured and would certainly have been offered compensation if he would renounce his entitlement to the See of Down and Connor. Like the hero of the Czech novel The Good Soldier [and scamp] Švejk, Magrath did not see any sense in being a hero and decided that if the Queen of England was so keen to make him an Anglican, it would be churlish to refuse. Accordingly, he did what she wanted, conformed to Anglicanism in his own way, and was released from prison.

Having allowed sufficient time to pass to earn full appreciation of the enormity of his sacrifice, he sent a letter to the Privy Council in Ireland asking them to kindly inform him what Her Royal Majesty and Their Excellencies had decided to grant him. Could it be the dignity that he had formerly held? Could it be another, or could it be—Heaven forfend—no dignity at all? It would make admirable sense to return him to Down and Connor (or rather return it to him), because he knew the place and could serve Her Majesty much better and more effectively than if he was living in any other part of Ireland. All of which made good sense.

However, Myler took pains to prove that he was not a greedy person. If Her Majesty would not change her mind, he would be happy if she granted him whatever she thought suitable for him, with one reservation: he would prefer some safe place where her rule was observed, because he had no desire to live among those rebellious and lawless Irish. Now, if Her Majesty could see her way to giving him some modest little bishopric in the English part of Ireland, he begged to draw it to her attention and to the notice of the noble members of the Council that the Diocese of Cork and Cloyne had been vacant for a long time, and he would gladly accept it. Of course he would prefer Down and Connor, because he could serve Her Majesty better there.

Did they know that there and in the neighbouring districts he had many friends and relatives? He admitted that some of them were rebels, but he would hope that, by his advice and persuasion, he could bring them back to peace and submission to Her Majesty. He would also publicly speak the true doctrine to the best of his ability, and no monk or Papist would stop him.

He had no intention of being pushy, but it was a good opportunity to remind Her Majesty that it would make sense to grant him those minor benefices—priories, simple rectories and chapels in Clogher—that the Bishop of Rome had given him. Their rent or taxes would provide him with a modest living. It would be no bother to Her Majesty to write to Lord Conor Maguire to release them completely and effectually to him. After all, they had been usurped by Papists and the Queen’s rebels.

Myler then added a sad postscript reminding Their Excellencies that he was ‘bereft of all human help’ in that ‘renowned kingdom’ (England) and that there was no-one from whom he could hope to obtain a gift or a loan to get him back to Ireland. He would be very grateful if they requested Her Highness to grant him in some way the money that he needed for his journey home. He signed his letter, which was written in Latin, Milerus Magrath, Irishman.

His approach was successful. On 18 September 1570 Magrath was appointed Bishop of Clogher by Elizabeth; within six months he had been upgraded to the Archbishoprics of Cashel and Emly in the south. No doubt it helped that he had offered to hand over Shane O’Neill, his foster-brother, to prove the genuine nature of his conversion.

I do not know if Myler ever met Elizabeth, but at a distance he was certainly a favourite or had influential friends at court. He was obviously able to charm people, because the Queen, in a letter to Sir Henry Sidney in March the same year, recorded the opinion of the Anglican Bishop of London and others that Myler was esteemed a fit person to return to Ireland and, ‘if no contrary thing might be found in him,’ should be appointed to some ministry. She ordered Sidney to have some bishops and other learned men confer with Myler; and since, in her opinion, he would be found right and serviceable for the church, he should be ‘used with more favour because of his conformity’ as an example to persuade other clerical gentlemen who had gone astray—i.e. had remained faithful to Rome—to ‘leave their errors.’ She pitied poor Myler and wanted Sidney to ensure that the bishops would look after him ‘for his relief and sustenance and to be thereby comforted to continue in the truth.’ Our hero appreciated being comforted.

In spite of this kind letter, Elizabeth was not totally taken in and requested Sidney to have the formidable Adam Loftus, Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and eventually Lord Chancellor, to investigate, together with the Bishop of Meath, Magrath’s ability and judgement in Protestant doctrine.

After the collapse of the Berlin Wall many centuries later, the files of the East German Ministry for State Security, the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit or Stasi, were opened up in the former German Democratic Republic, and people were astonished to learn who and how many had been supplying the Stasi with information about their neighbours and families over many years.

Towards the end of the twentieth century the Hungarian writer Péter Esterházy wrote a novel about his family, Harmonia Caelestis. A few years later he was given access to Stasi documents in which he recognised his father’s handwriting and discovered that his father, under the code-name Csanádi, had been giving information to the Hungarian secret police from 1957 to 1980. He republished the book, now entitled ‘corrected edition’, and inserted corrections, in red print, that revealed what he had discovered in the secret files.

Elizabethan Ireland was not unlike the GDR or Hungary in this respect. Informers supplied Dublin Castle and London with secret reports, and Magrath was one of those informers. He contacted the Lord Deputy, frequently denouncing rebels and active Catholic bishops and priests. His reports are still preserved in the English State Papers collection at the Public Record Office in London.

Such denunciations could have serious effects, because failure to take the oath that recognised Elizabeth’s supremacy could lead to imprisonment or even death, on charges of treason and disloyalty. A typical report described Redmond O’Gallagher, Bishop of Derry and Pope’s legate, who attended the Council of Trent (1545–63). Ironically, it accused him of riding from place to place with pomp and ceremony as in the times of Catholic Queen Mary (as if Myler would ever do such a thing).

In a typical letter Magrath noted that the clergy were using the new Gregorian calendar, registered a complaint about Cornelius MacArdle, Bishop of Clogher for forty years, who, in spite of being hauled up before various inquisitors, had not switched over to the new allegiance, and denounced Tadhg O’Sullivan, a Franciscan who was preaching from house to house in Waterford, Clonmel and Fethard, and James O’Cleary, who acquired a dispensation for the town of Galway as a reward for killing some holy Spaniards.

Magrath also provided lists of priests who had been ordained by Bishop Dermot Creagh or MacGrath, Bishop of Cloyne and Cork, and others who had been ‘seduced from their loyalty [to the Queen] and reconciled [by Creagh] to the Pope’s laws.’ He also informed the authorities that there were still sixteen monasteries functioning in Ulster, and that Bishop Creagh was living openly ‘without pardon or protection’ and exercising his jurisdiction as Pope’s legate.

Magrath described Creagh as ‘one of the most dangerous fellows that ever came to Ireland, for such credit that he draws the whole of the country to disloyalty and breaking of the laws.’ Simultaneously Magrath, in a letter to his wife, described Creagh as his cousin ‘Derby Kragh’ and in letters to friends told them to send Creagh ‘out of the whole country for there is such a search to be made for him that unless he is wise he shall be taken.’ Indeed at a later point Magrath would be accused of sheltering and giving warning to Creagh when the government had plans to capture him. A commission report stated that Magrath was a ‘notorious papist’ who would rather die than capture Dermot Creagh.

It is interesting that much of the criticism of Myler came from Protestant sources. Obviously envy must have played a part in this and also puritan begrudgery of a flamboyant rascal. It would have stuck in the throat of many that this colourful Irishman collected church livings like stamps and at one and the same time was Bishop of Cashel, Emly, Waterford and Lismore—all prosperous livings. His enemies accused him of ‘whoredom, drunkenness, pride, anger, simony, avarice and other filthy crimes.’ He was not helped by the fact that the Lord Deputy from 1588 to 1594, Sir William Fitzwilliam, did not like him; but then the list of Fitzwilliam’s ‘not favourite’ people was long, and the Lord Deputy himself would be accused of partiality to bribery and corruption.

One can imagine Fitzwilliam rubbing his hands when he read that Magrath was a dissembler and, even worse, a man ‘of no standing religion who purposes to deceive God and the world with double-dealing,’ that he had received large gifts from the Pope and owed more to him than most men in Ireland, that he hoped that if the Protestant cause was overturned, he would get more from the Pope than the people who had suffered, that he sheltered bishops from Rome in his house and had them baptise his children as Catholics and then denounced one of them when what he was doing became known, that he imposed severe cash charges on his (Protestant) clergy, which drove some of them out of his dioceses, and then collected this money for himself, and that he beat people cruelly, and once, when a poor tiler was looking for unpaid wages, cut all the flesh from the man’s forehead to the crown of his head and then slapped it back on the bare bone, telling him to take that for reward. (In this case the witness could not testify to the ‘This is your reward’ part of the story.) Definitely roguish behaviour, if true.

Apart from informing on people, Magrath kept in favour by supplying intelligent analyses of the political tendencies in Ireland and the role played by the different discontented parties: the ‘old Irishry, which greedily thirst to enjoy their old accustomed manner of life, as they call it,’ the ‘remnants of rebels whose ancestors were worthily executed, or forced into banishment with loss of lands and livings,’ and ‘the practising papists, which under pretence of religion will venture life and living, and do daily draw infinite numbers to their faction.’ He described this third group as ‘very dangerous and crafty, being the strongest, the richest, the wisest, and the most learned sort.’ Obviously what they might lose, Myler would gain.

His tongue must have been in his cheek when, himself the husband of a Papist wife and father of Papist sons, he wrote that ‘the lack and use of the right knowledge of God’s word is the chiefest cause of rebellion and undutifulness against the Queen.’ He was also shrewd enough to recommend the translation of the Bible into Irish, a revolutionary step when writing to people who despised and ignored the barbarous tongue. His own tongue had definitely moved over to the other cheek when he advised his readers that the Irishry were weary of the Romish bishops, seminary priests or friars for their sinful and evil examples.

A Catholic historian, Philip O’Sullivan Beare, writing in 1618, implied that Myler, having been given his bishopric...