1 Immateriality and Intermateriality: The Vanishing Centrality of Apothecary Ware in Russian Medicine

Clare Griffin

In the summer of 1663, a specific person was sent to a specific place in search of a specific object for a specific purpose. The person was Master Ptitskoi, known in Moscow as a master of ceramics, especially those for apothecary purposes. The place was Gzhel, a village not far from Moscow famous then and now for its clay. The object was the Gzhel clay itself. And the purpose was to source and exclusively create apothecary ware from that clay for the Moscow court. Making a close reading of the order that sent Master Ptitskoi on his errand for Gzhel clay reveals how one short text can provide a broad insight into the complex material world of Muscovite pharmacy.

Material culture studies have become an essential part of the history of science, technology, and medicine, with investigations devoted to everything from water pumps to natural history collections to materials of chemical analysis. Each group of objects gives us a different perspective on the role of materials within historical, scientific, and medical practices and opens up new ways of thinking about the history of science. Here, I argue for the inclusion of one group of objects to which little attention has thus far been devoted, but which has unique features that merit attention: apothecary ware. Apothecary ware, in particular that subgroup of vessels used to transform ingredients into medical drugs, is a group of objects that functioned in an unusual way, existing only to interact with other objects. It was a group of items in heavy use at the seventeenth-century Russian court, where medical drugs were of notable interest.1

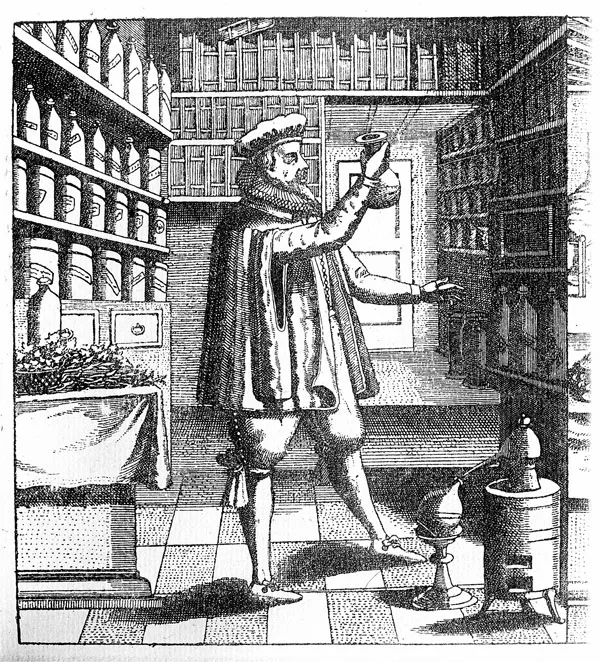

What were these objects? Apothecary ware is a category of objects that both contains different subgroups and is related to other categories of object. If one were to walk into an early-modern apothecary shop, the first thing to catch your eye would likely be ornate storage jars, typically ceramic, and often beautifully decorated as well as labeled as to their contents (see Figure 1.1). In the eighteenth century, Peter the Great had such storage jars, emblazoned with the Imperial insignia.2 Many of those storage jars, sometimes also referred to as medical ceramic ware or pharmacy jars, would contain individual natural objects, being kept ready to be processed into ingredients. That production process takes us to a range of tools for creating medicines. The simplest kind were to cut or grind ingredients, such as a stone mortar and pestle. This transformed raw materials into ingredients suitable for being mixed together into medicines. Many early-modern medical drugs involved alcohols, so there was also equipment for brewing and fermenting alcohol from a range of natural objects, such as grains and fruits. This again involved tools for smashing up the raw materials, as well as heating them, and storing them during the long brewing or fermenting processes. Those tools were often metal or wooden. Those alcohols could then be distilled into stronger alcohol, involving another set of objects to heat the liquid, and glassware tubes and vessels to separate out the alcohol from diluting components. Once produced, those liquids would be stored in glass bottles. This already complicated processing of natural objects with the help of multiple kinds of technical object only takes us as far as creating ingredients.

The apothecary then needed to put these ingredients together into a medical drug according to a recipe, involving the paper material objects of a book or a physician’s prescription on a scrap of paper. This could be a simple process, such as mixing a dried herb into an alcohol, which could be done with a glass or ceramic vessel and a wooden spoon. Or it could be a more complicated process, involving multiple steps, heating, and mixing. Such involved processes again required objects to create and to use fire safely, and vessels and stirring tools that could withstand heat, such as metals or ceramics. In either case, the apothecary would also use weighing and measuring devices such as metal scales. Once this process had been completed, the resulting medical drug would again go into a storage jar, either a large ceramic jar like those for natural objects and ingredients or a smaller vessel for a patient to take away. Apothecary ware is most properly the ceramic vessels for the production and storage of medical drugs, but it is important to remember that those items were part of a broader constellation of technical pharmacy instruments being brought into interaction.

We can study this apothecary ware using the perspective of material culture studies. Material culture studies places objects as the focus of historical inquiry, which leads to multiple further roads of analysis. Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello have highlighted the historical existence of objects themselves, showing things can be different in different contexts, and thus how individual objects then effectively lived multiple lives when used and traded globally.3 Looking at the material can also take us to considerations of culture. Scott Manning Stevens has shown how the tomahawk has been used as a key part of the racist stereotype of the Haudenosaunee (sometimes also called Iroquois) Native Americans as inherently violent in white American culture.4 Objects can also tell us about knowledge and expertise. Pamela Smith has looked at what objects can add to histories of knowledge, asking, “We usually think about the production of knowledge as resulting in a body of texts, but what kinds of knowledge result from the production of things?”5 We could rephrase that question here as: what kinds of expertise were inherent in the creation and use of apothecary ware to create medical drugs in Muscovy? And what does that then tell us about the possibilities and limitations of material culture studies? Directing our attention toward apothecary ware adds to our understanding of material culture as a perspective, and also reveals underappreciated facets of Muscovite science.

When I talk about apothecary ware, I am narrowly concerned with apothecary ware as objects that destroyed raw materials and, in the process, created medical drugs. These items functioned in a very specific way. They were objects that only existed to interact with, and indeed destroy and create, other objects. Their materiality—a term I use here to mean the sum total of their material properties—was fundamentally an intermateriality. In the Muscovite case, we do not have any identified examples of extant apothecary ware; the destructive objects were themselves destroyed. In this way—and others, as we will see later—these intermaterial objects are also immaterial. As such, lost Muscovite apothecary ware for creating drugs represents a subset of materials that behave in a unique fashion and so provide a rare opportunity for material culture analysis.

Apothecary ware can give us new perspectives on two vital trends within material culture-informed histories of science and technology: material specificities and object agency. Pamela Smith, in her consideration of early-modern West European artisanal scientific practices, has written, “Artisanal knowledge was inherently particularistic; it necessitated playing off and employing the particularities of materials (including, in some cases, the impurities in the material).”6 This idea of materials and objects as each having some notable particularity, and the role of science as understanding and manipulating that particularity, has been key. We can see this in other studies, like Ursula Klein and Wolfgang Lefèvre’s Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science, a study of chemistry as the science of understanding, manipulating, and experimental production of materials.7 Apothecary ware had particular qualities, but those qualities were necessarily judged in terms of how they interacted with other things. Rather than looking at the particularities of the subjects of experimentation and artisanal creation, we can look at the particularities of the wares that facilitated creation. What was it about the specificity of apothecary ware as an object that allowed it to create another object?

Histories of technology informed by material culture have particularly been interested in the idea of object agency.8 Technologies move, interface with other objects, and interact with people. One example of this approach is Marianne De Laet and Annemarie Mol’s work on the Zimbabwe Bush Pump, showing how the pump only really fulfils its function of providing healthy drinking water when it is correctly installed in its location and used and maintained by the local community.9 Objects like the Zimbabwe Bush Pump have their own kind of object agency. In the case of the Zimbabwe Bush Pump, De Laet and Mol talk about the pump as an actor, as when it functions it functions only in interaction with other materials and with people.

Apothecary ware presents a new perspective on this key issue of object agency. There are two basic ways in which a vessel designed for the production of drugs could work. In one variant, the specific properties of the vessel would actively take part in the transformation in some way, exerting object agency in the process. In the other variant, the vessel would be chosen to have the specific property of being chemically inert and would so have a meaningful and purposeful lack of object agency in the process. Apothecary ware thus complicates this already tricky question of agency, as it sits on a liminal point of having partic...