eBook - ePub

Identities, Ethnicities and Gender in Antiquity

- 293 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Identities, Ethnicities and Gender in Antiquity

About this book

The question of 'identity' arises for any individual or ethnic group when they come into contact with a stranger or another people. Such contact results in the self-conscious identification of ways of life, customs, traditions, and other forms of society as one's own specific cultural features and the construction of others as characteristic of peoples from more or less distant lands, described as very 'different'. Since all societies are structured by the division between the sexes in every field of public and private activity, the modern concept of 'gender' is a key comparator to be considered when investigating how the concepts of identity and ethnicity are articulated in the evaluation of the norms and values of other cultures. The object of this book is to analyze, at the beginning Western culture, various examples of the ways the Greeks and Romans deployed these three parameters in the definition of their identity, both cultural and gendered, by reference to their neighbours and foreign nations at different times in their history. This study also aims to enrich contemporary debates by showing that we have yet to learn from the ancients' discussions of social and cultural issues that are still relevant today.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Part I: Masculinity, Dress and Body

Ionians, Egyptians, Thracians: Ethnicity and Gender in Attic Vase-Painting

François Lissarrague

More than 40 years ago, around 1977, I began a dissertation project dealing with ‘the representation of Barbarians’ in Attic vase-painting. The topic was suggested to me by Pierre Vidal Naquet, to whom I had submitted a paper on the fight between Pygmies and cranes. He was at that time interested in ‘marginals’, forms of alterity and ‘otherness’ (without any Lacanian perspective). No one spoke of ‘ethnicity’. As to ‘gender’, that was still to come. The great novelty of the time was, some years later, the development of the history of women.1

During that research on ‘Barbarians’ I was using an ‘emic’ concept, βάρβαροι (‘barbarians’), and dwelled on a saying attributed to Thales, who was happy “to be a human being, not an animal; to be a man, not a woman; to be a Greek, not a Barbarian”.2 This Hellenocentric scheme fit perfectly with Athenian vase-painting, and I only had to collect the evidence and organize it to produce a relatively complete catalogue of such documents. I never wrote that dissertation, because a German colleague published his own dissertation under the title Zum Barbarenbild in der Kunst Athens.3 So I shifted my project, limiting it to Thracians and Scythian warriors.4 However, I used some of that evidence in separate articles, written in collaboration.

The first one deals with images of comasts commonly called ‘anacreontics’, in the scholarly tradition; it was written in collaboration with Françoise Frontisi and published in 1983.5 The second, written with Jean-Louis Durand, analyzes the story of Herakles and Busiris.6 A third group of images was discussed at length with Marcel Detienne, when he was working on Orpheus; it was not published as a joint article, but I dedicated a later paper, published in 1994, to him: “Orphée mis à mort.”7

The reason for turning back to these articles is not just selfish nostalgia; it seems that they can be usefully combined in terms of articulation around the notions of identity, ethnicity, and gender. This last notion, in particular, which was not used in these early papers, sheds an interesting light on the categories at stake in these three groups of images.

In this short paper I will briefly summarize the main aspects of each of these three series of pictures, using a sample of characteristic examples, in order to underline the relationship they suggest between identity, ethnicity, and gender, and to show how gender, as an analytical tool, helps to better understand the contrasts involved in these groups of representations, and also to better understand the way images build a network of discriminating signs structuring the Athenian imagination.

1 ‘Anacreontics’

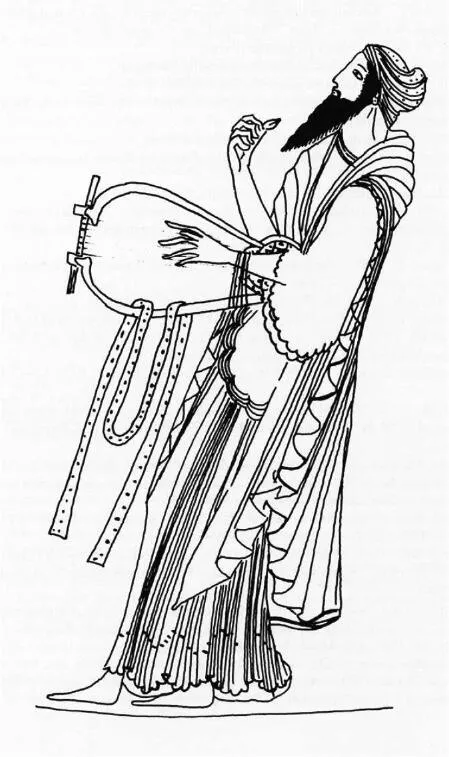

Let us begin with the so called ‘anacreontics’.8 It is a group of vases showing a bearded figure in a long chiton, wearing a σάκκος (‘headgear’), sometimes earrings, these last two signs being a visual mark of female dress (fig. 1).9

Fig. 1: Boston 13.199, red-figure lekythos.

When such figures wear an open dress, the male sex is visible, which demonstrates that these figures are not bearded women dressed as men, but the opposite: men dressed as women, playing the Other (fig. 2).10

Fig. 2: Paris, Louvre G4bis, red-figure cup.

The beard is a graphic way of showing the maleness of these figures. Some of these images are labelled with the name of Anacreon and some authors think they are portraits of the poet himself (fig. 3).11

Fig. 3: Syracuse 26967, red-figure lekythos.

We have demonstrated that this is not the case; the word ‘anakreon’ appearing on some vases is not a label naming the poet, but a reference to a poetic genre, and to a kind of κῶμος (‘dancing group’), popular in Athens when Anakreon paid a visit to that city.

This series of images plays with the reference to the Ionian world, without really marking a specific ethnicity, as the Athenians do not need to distinguish themselves form the Ionians. In this series, it is the experimentation of feminine alterity which is displayed, in the frame of the Dionysiac practice. Gender is temporarily put into question as a category, which can elucidate the shift from anatomical maleness to social experimentation of the other sex.

2 2 ‘Busiris’

The Heracles and Busiris series has much to do with ethnicity. Heracles reaches Egypt at the time of a drought; Busiris, the Pharaoh, in order to obey an oracle, sacrifices every oncoming foreigner; so Heracles is to be sacrified. We see him taken to an altar, and suddenly realizing he is the victim; he fights against the priests and destroys the entire order of the ritual. We were interested, Jean-Louis Durand and myself, in this story because these images show a kind of human sacrifice in which the sacrificial ritual is inverted, and all the elements of the standard sarifice are displaced; the sacrificial basket is falling down, and the μάχαιρα (‘sacrificial knife’), the sacrificial knife, which is almost never shown in standard sacrifices, is here clearly visible. By this displacement, these images reveal what is usually hidden, or at least not shown, in the standard sacrifice. Clearly these images have nothing to do with ethnographic documents; they do not describe the Egyptian way of sacrificing. They show how the Greek vase-painters imagine the Egyptian episode in the Heracles saga. All the instruments reproduced in these pictures are perfectly Greek (altar, basket, knives, spits, etc.).

More interesting, in terms of ethnicity and gender, is the way the Egyptians are conceived and depicted. On a pelike by the Pan painter (fig. 4),12 the Egyptians are bald, pug-nosed, and their chitons are systematically lifted to show their genitals, and that they are all circumcised. A different masculinity is exhibited by the painter, clearly a non-Greek masculinity. On other images in that series, the Egyptian priests wear long dress and earrings, which are feminine markers (fig. 5).13

Fig. 4: Athens NM 9683, red-figure pel...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Part I: Masculinity, Dress and Body

- Part II: Gender, Political Leaders and Ethnic Identity

- Part III: Cleopatra’s Survival and Metamorphosis in RomanPoetry

- Part IV: Love, Oriental Ethnicity and Gender in Roman Literature

- Part V: Constructing or Deconstructing Female Ethnicity in Late Antiquity

- List of Contributors

- General Index

- Index Locorum

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Identities, Ethnicities and Gender in Antiquity by Jacqueline Fabre-Serris, Alison Keith, Florence Klein, Jacqueline Fabre-Serris,Alison Keith,Florence Klein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient & Classical Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.