![]()

1 Eohippus to Equus

Wild Horse breathed on the Woman’s feet and said, ‘O my Mistress and Wife of my Master, I will be your servant for the sake of the wonderful grass.’

Rudyard Kipling, The Just So Stories

Deep in the rich tropical forests of prehistory, padding its cautious way on long-nailed paws, a small deer-like animal browsed on low shrubs and the rushy margins of marshland pools. This little creature was not only the ancestor of the horse, it was also something of a red herring. When its remains were discovered in the 1870s by American palaeontologist, Othniel C. Marsh, he came to the conclusion that this was the missing link to an understanding of the development of the modern horse.

Some years earlier, in the 1840s, fossil remains from the same genus were found in London by Sir Richard Owen, who named it Hyracotherium, a name considered today to be more accurate and less misleading. However, with the discovery of ‘horse’ fossils in America, long considered to have no indigenous horse breeds, this small creature was named twice, and the second name, Eohippus or ‘dawn horse’, while more romantic, led to a misconception.

The first part of this was that the Eohippus was an early horse, when it was actually also the ancestor of many other animals, including the tapir and the rhinoceros. The second was that it was not only an early but a primitive, as yet unfinished, model of the horse we know today, something along the lines of a work-in-progress. The horse we know today would not have survived long among the swampy tropics of the Eocene era, while the Hyracotherium was perfect for its own time and changed little over 20 million years. It had legs which would flex and rotate to allow a wide range of movement and had developed for a soft-soiled environment, with four toes on each front foot and three on each hind. It walked not on hooves but on strong nails and a ‘heel’ in the form of a hard pad. The vestigial remains of this pad are thought to be found today on the horse in the ergot, a small nub of hoof-type material on the point of the fetlock. It had a small brain and eyes on the front of its head, not the sides like a horse, illustrating that it was a creature needing forward, rather than peripheral, vision. This suited its dense and sheltered environment, while a coat pattern of soft spots would have been its most likely colouring, providing camouflage among the leafy shade of its habitat.

The skeleton of a Hyracotherium. | |

Skeletons of the Hyracotherium have been found in America and Europe and suggest that its size ranged from around 25 centimetres (10 inches) to maybe twice that at the shoulder, and that it had a similar wide variety of shape and size across its range of locations. It seems likely to have spread across the land bridges that once joined the continents of America, Asia and Europe and remained at this evolutionary stage for several million years. It is easy to forget, when comparing the animals of prehistory with those familiar to us today, that the theory of evolution does not suppose the linear movement of any organic form towards a perfect end. While the changes over millennia may be seen as developments, this does not suggest that the original form was imperfect, but rather provides evidence of an ability to adapt that ensured that certain branches of the family survived and others died out.

Mid-way on the long journey between Hyracotherium and the hoofed Equus of today, during the Oligocene period, came the Mesohippus, by way of the Orohippus, the Epihippus and some 20 million years. Still small at 45 centimetres (18 inches) but starting to develop teeth that could manage a greater range of foliage, and feet that could cope with harder and more varied terrain, the Mesohippus was the natural response to a cooling climate. As abundant grasslands spilled across the surfaces of the changing landscape to take the place of the receding forests, the teeth of this animal became larger and more durable. Also, the longer legs suggest that greater speed had become important, while with longer teeth came a larger skull with more lateral vision, all as adaptation to the more open habitat. Slowly, the Mesohippus was changing from a shy forest creature, relying upon concealment for safety, to a flight animal whose speed and agility were its best means of defence.

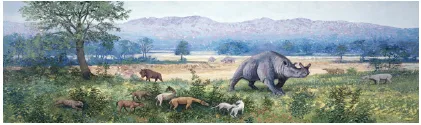

Artist’s reconstruction of the world of the Mesohippus.

As the earth shifted gradually towards a more temperate climate over the next several million years, the little creature grew taller, with its toes becoming vestigial. It started to take its weight on a central toe, which gave it a longer stride, while its teeth became more recognizably those of a grazing animal. The Miohippus overlapped with the Mesohippus for around 4 million years and fossil evidence suggests that the different species, and other variations that had split off from the Mesohippus, coexisted. Such families of related animals, ‘clades’ to the palaeontologist, illustrate the diversification of species in order to take advantages of various changes in their surroundings. This means that while they may follow a general tendency, such as, in the example of the Mesohippus and its relations, having a larger brain than most herbivores, they each also develop traits of specific use to their own location and climate. The negative aspect of this is that, should those specifics change, a complete branch of the family may be wiped out quite suddenly. Those who survive may simply be in the right place at the right time, rather than having any superior qualities.

While a simple overview might suggest that the horse evolved from a small animal into a large one, palaeontologists find that the different species grew both larger and smaller than their progenitors, again to adapt and survive. In The Great Evolution Mystery, Gordon Rattray Taylor concludes that

the fact is that the line from Eohippus to Equus is very erratic. It is alleged to show a continual increase in size, but the truth is that some variants were smaller than Eohippus, not larger. Specimens from different sources can be brought together in a convincing-looking sequence, but there is no evidence that they were actually ranged in this order in time.1

Therefore, although Othniel Marsh’s belief that ‘The line of descent appears to have been direct’2 was presented as fact for almost a century, today it is widely accepted that the evolutionary picture is far more complex.

Around 6 million years ago, emerging from the changes in teeth, body size, leg length and facial structure that had occurred during the Miocene era, came animals looking not unlike a mule that became the source not only of the modern horse, but also of zebras and donkeys in all their variations. After a successful few million years for several three-toed plains grazing species, the line that led to the horses of today developed with the formation of side ligaments that supported the central toe and eventually superseded the two additional toes. This change to a single hard toe, with tendons that allow the gather and release of energy in a springing movement, meant that Pliohippus, along with the wonderfully named Astrohippus and Dinohippus, were the earliest true relations of Equus, the genus of all modern species.

The first Equus caballus, the ancestor of today’s horse, is thought to have descended from the Pliohippus relatively recently, around one million years ago. Considering the rate of change over the previous 50 million years, this represents something of a rapid development. The last period of glaciation ended approximately 10,000 years ago and as this final Ice Age receded the more clearly defined forms of Equus established themselves: horses in Europe and Western Asia, asses and zebras in the north and south of Africa, and onagers in the Middle East. While it is commonly accepted that horses were introduced into the Americas in the sixteenth century by Spanish conquistadors, their ancestors had roamed the continent up until 8,000 years earlier before becoming completely extinct there for reasons not fully understood. Climate change, food shortage and predators have been put forward as possibilities, though there is another consideration, which, if true, was perhaps something of an omen for the horse. Excavations of prehistoric cooking sites indicate that horses had become an important part of the human diet, leading to growing consideration of the impact of human predation on the early horse population. Archaeological evidence suggests that within 2,000 years of the arrival of man in North America, horses, along with other herd animals including camels, were gone. Archaeologist and ecologist Paul Martin concludes that ‘This extinction was postglacial in time and affected in the main the larger animals. The principal factor isolated as cause is the appearance of man.’3

| Cave painting of hunters from Indian Creek, Utah. |

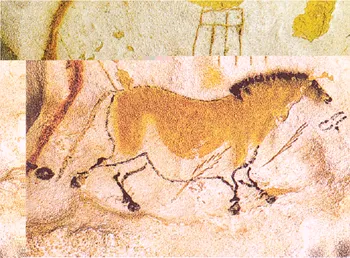

A palaeolithic painting at Lascaux, France.

The wide distribution of early horses and the way in which they have always survived by adapting to their environment are partly responsible for their impact upon human development. At its simplest level this can be seen by observing any modern horse. There is a tendency today to provide rugs and winter shelter for horses, which makes them more comfortable but inhibits their natural capacity for adaptation. Left to themselves, horses will grow a winter coat and shed it depending on location. Of course, many would die in very severe weather or a time of food shortage, so as the horse developed, its survival became dependent upon its strength and resilience. The animals that could adapt and cope with hardship most readily forged their way through the years, developing the core features that determined their future. Different types of horse evolved to suit the climates they inhabited, so horses in hot, dry climates developed slender limbs and fine skin with veins prominent on the surface to aid cooling. Cold-climate horses developed as small and solid, with coats which readily grow dense in the winter and legs which develop long hair, known as ‘feather’, especially round the fetlocks, the horse’s heel, to shed water.

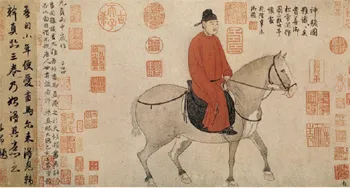

The ample figure of this horse indicates the successful career of his rider, a red-coated official, in a coloured ink drawing by Zhao Mengfu, c. 1296.

Among many types a spotted horse will occasionally appear. Examples may be found in images as old as the cave paintings of Peche-Merle in southern France which date to around 20,000 BC, as well as Etruscan tombs in Italy and burial sites at Hallstatt in Austria dating from around 800 BC. They are found decorating weapons of the Celts of northern Europe and the nomadic steppe horsemen of south-western Russia. They also appear in legends, such as those of the Persian hero, Rustam, whose horse, Rakhsh, is often depicted with a red spotted coat, and are particularly popular in early Persian and Moghul art. From the fifteenth century onwards, the selective breeding of spotted horses became prevalent in very different cultures, with the most well known being the Knabstrup of Denmark and the Appaloosa of the Nez Perce tribe of north-eastern America, both descended from early Spanish strains. While these have developed into clearly defined breeds, the spotted gene seems to spring up here and there across time and location to recall that, like people, horses have a common ancestry and were originally separated by time and distance rather than blood.

| Spotted horses and prey in a Persianstyle carpet from 17th-century India. |

The human desire for order and reliability led to selective breeding, but the raw materials with which humans had to work were already established into particular types suited to the environment in which they lived. Most of these ancestors of modern horse breeds may have gone on to be shaped by human intervention but they were established by one of the key features that make a hors...