![]()

Case Studies for Urban Governance

Present-day cities and countries

1. Sibiu, Romania (Plague, 1510)

2. Agra, India (Plague, 1618–1619)

3. Bristol, England (Plague, 1665–66)

4. Veracruz, México (Smallpox, 1826)

5. York, England (Cholera, 1832)

6. Naples, Italy (Cholera, 1860–1914)

7. Harbin, China (Plague, 1910–1911)

8. Terre Haute, USA (Smallpox, 1902–03)

9. Nairobi, Kenya (Plague, 1895–1910)

This page: Map indicating the locations of case studies in this section of the book. (Map in the public domain, with annotations drawn by Andrew Bui.)

Right page: A man sitting at a table examining passports, during a plague epidemic in Mandalay. Photograph, 1906. (Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.)

![]()

The eastern fringes of ancient and medieval Central Europe served as a trade crossroads for land routes that linked Europe and Asia. Beginning in the 14th century, the region facilitated the transport of precious Levantine wares and commodities such as silk and spices, a role that earned privileges for the urban communities en route. Traders from the Balkans to the Baltic moved from Istanbul via Edirne and Nikopol to Kraków, Toruń, and Gdańsk.1 An important stretch of this route led through the eastern half of the Kingdom of Hungary, crossing the range of the Carpathian Mountains coming both from Transylvania (presently part of Romania) in the south, and the modern-day Slovak-Polish border in the north. The names of the most important stopovers on this stretch, Sibiu (Szeben, Hermannstadt), Braşov (Brassó, Kronstadt), Cluj (Kolozsvár, Klausenburg), Oradea (Várad), and Košice (Kassa, Kaschau) took many forms, indicating the multiethnic populations of towns.

Trade routes across Hungary facilitated the movement of goods, but they also enabled the spread of infections. This was well known to the Bishop of Transylvania in 1497, who complained that “Oradea was again infected by those coming from Braşov.”2 In addition to disease, public health ideals and models of charity also spread along these trade routes and were increasingly reflected in the distribution of small, municipally funded leper houses (leprosaries) placed on the outskirts of cities and towns. Typically, patients were separated and provided with material and spiritual care, not with medical cures, as leper houses recorded priests on their payroll, not doctors. These sites were the first urban institutions of communal care suitable for isolation practices. After the decrease of leprosy in the late 15th century, they were converted for use during epidemics identified by contemporaries with plague or with other contagious diseases.3

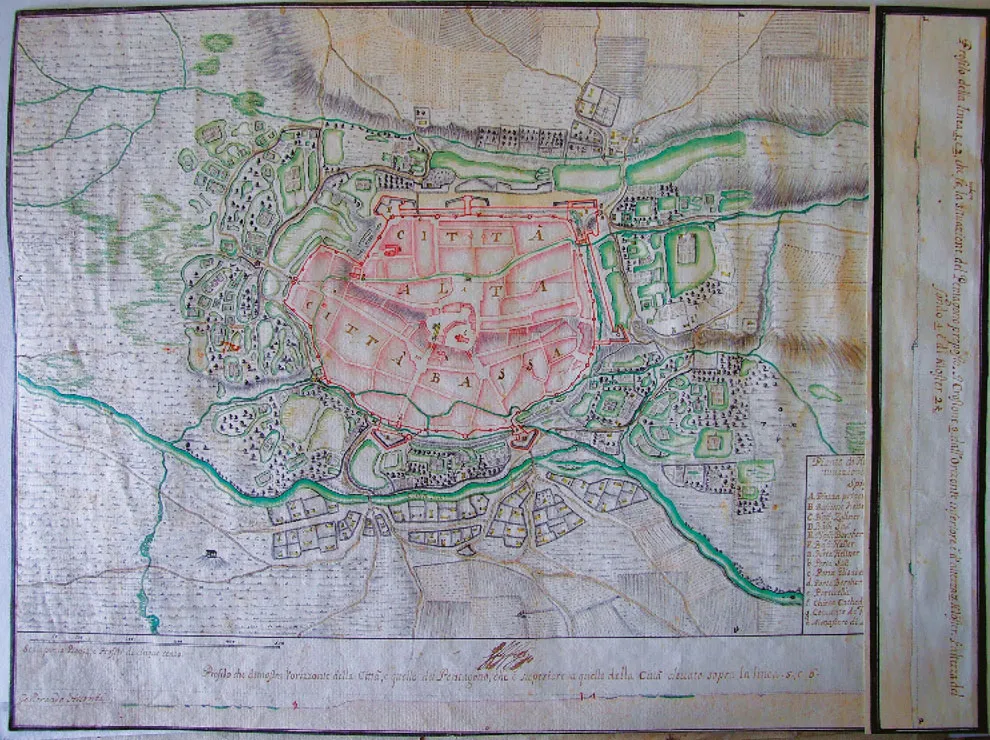

Early 16th-century Sibiu was a wealthy merchant city in the Kingdom of Hungary with approximately six thousand inhabitants, most of them Germans, the so-called Transylvanian Saxons (Figure 1.1).4 The city was the key entry point for the land route of the Levantine trade across the Carpathian Mountains via the Turnu Rosu Pass (Figure 1.2). The city authorities invested a significant portion of their trade wealth in communal welfare. The municipal almshouse was built in 1292, an early date for such an institution in Hungary. Other specialized institutions dedicated to public welfare included a leper house from 1475, a town pharmacy called the Black Eagle built in 1494, and a hospital for syphilitic patients, constructed in 1501. Sibiu was also among the first urban centers in East Central Europe to employ municipal physicians. Little is known of most of these professionals, but they were formally trained at universities in the practice of medicine and often came from distant or even foreign places of origin such as Austria and Italy. By employing these municipal physicians and offering handsome salaries, the city imported up-to-date medical knowledge and expertise.5

Case study: Plague in Sibiu, 1510

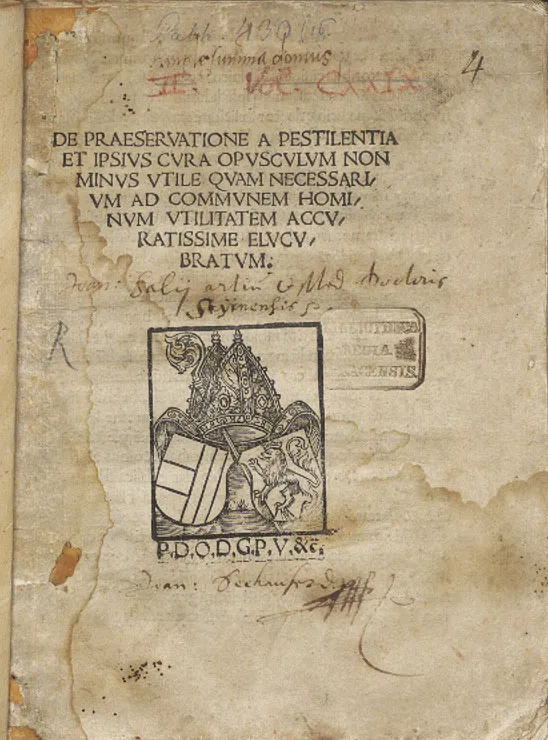

In 1510, a severe outbreak of the plague spread across Hungary. King Wladislas II (r. 1490–1516) and his children fled Buda, the capital, and the diet had to be interrupted. Plague and subsequent famines were reported closer to Sibiu in the region of the Timiș (Temes) River.6 Hans Saltzman of Styria (d. 1530), Sibiu’s town physician at the time, was an Austrian who had previously studied in Vienna and Ferrara and practiced medicine in Moravia.7 The appearance of the plague in the Transylvanian city was the impetus for Saltzman’s text “A little work on the prevention of the plague and its cure, just as useful as necessary, explained accurately for the use of the common man” (Figure 1.3).8 Saltzman completed the Latin booklet in August 1510 and had it printed in Vienna in November of that year, dedicating it to the royal judge Johannes Lulay (d. 1521) and Sibiu’s city council.9

Saltzman prepared a German edition of his work for use in Styria eleven years after the initial Latin printing.10 By that time, the author was a member of the medical faculty of the University of Vienna and the court physician of Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria (r. 1521–1564; from 1556 also Holy Roman Emperor as Ferdinand I), who sponsored the publication of the translated and revised booklet in the wake of a new plague outbreak in 1521 (Figure 1.4). The trade-route setting of Styria paralleled that of Sibiu in many ways. Situated in the northern foreground of the Alps and crossed by an important commercial artery between the Adriatic and the Danube valley, Styria was exposed to the dangers of infections carried by long-distance merchants moving from Venice through Villach and Graz to Vienna and beyond (Figure 1.5).

Saltzman’s booklets fit into a long tradition of more than three hundred such plague tracts that have survived from the years between the Black Death of 1347–50 and 1500.11 Given the characteristics of Hippocratic-Galenic medicine, medieval plague tracts were typically written with the needs of individual patients in mind. However, with the diffusion of the office of municipal physicians and the emergence of urban health boards, these publications began to address an audience of magistrates and other territorial authorities as well. The genre reached Hungary after some delay: the earliest plague tract known from medieval Hungary was copied in 1473 by János Gellértfi of Aranyas, a cleric in the Spiš (Szepesség, Zips) region in modern-day Slovakia (then northeastern Hungary).12 The original was composed by Johannes Jacobi, a professor of medicine at Montpellier (d. 1384).

Most plague outbreaks in premodern Europe have left behind few local sources, and this is also the case for the course and consequences of the 1510 plague in Sibiu. However, Saltzman’s two booklets, when taken together, offer a well-educated physician’s insights into the medical scenario. There are notable differences between the two texts. The Latin version of 1510 concentrates on the general causes of the infection and gives advice to individuals on how to prevent, diagnose, and eventually cure the disease. Apart from its dedicatory preface to the magistrates of Sibiu, it follows the usual pattern of earlier plague tracts. The German version printed in 1521 was written in the vernacular (and therefore potentially more accessible to the general public) and was complemented by a set of recommended public health measures for implementation by the civic authorities. According to Saltzman, such measures had led to the successful protection of the Transylvanian city eleven years earlier. The additional elements in the second version likely reflected Saltzman’s growing practical experience and accumulated knowledge.

![Page of a book with a decorative border and script. Book is by Hans (Johannes) Saltzman, and the title translated to English as “[A useful regulation against the plague by Doctor Hans Saltzman from Styria … explained for the use of the common man],”](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/2842645/images/67890000_C001_004-plgo-compressed.webp)