- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

WE HELD A FUNERAL FOR THE BIRKS BUILDING

The protestors are wearing Video Armour crocheted out of used videotapes collected from television and film studios by artist Evelyn Roth.

Angus McIntyre photo, 1974

At two p.m. on Sunday, March 24, 1974, a group of about 100 people, many of them students and professors from the University of British Columbia School of Architecture, came together in a mock funeral for the Birks Building, an elevenstorey Edwardian masterpiece at Georgia and Granville with a terracotta facade and a curved front corner.

Participants marched from the old Vancouver Art Gallery at Georgia and Thurlow, led by a police escort and accompanied by a New Orleans funeral band playing a sombre dirge. The mourners assembled under the Birks clock, an ornate iron timepiece that stood more than twenty feet (6.5 metres) tall and for decades had been a local landmark and familiar meeting place. For generations of Vancouverites, “Meet you at the Birks clock” was a common phrase.

On this day, it was too late to stop the demolition—it had already begun—but not too late to protest what author and historian Michael Kluckner and others have called an egregious act of architectural vandalism. The crew working on the new building across the road shut off the air compressors and laid down their tools. Reverend Jack Kent, chaplain of the Vancouver Mariners Club, officiated. A choir accompanied him.

Before the Birks Building stood there, the Canadian Pacific Railway built three office blocks at Georgia and Granville, some of the earliest office buildings in the city.

Vancouver Archives Str P73, 1889

Angus McIntyre, then twenty-six, grabbed his Konica Autoreflex T2 35mm camera and rode his bike downtown to record the event. “There was a gathering, a sharing of ideas, a choir performance and a laying of the wreaths,” Angus told me. “A small group of people wearing recycled videotape clothing put hexes on new buildings nearby. As soon as it came time to return to the art gallery, the band switched to Dixieland jazz, and the mood became slightly more upbeat.”

In March 1974, more than 100 people gathered by the clock at Granville and Georgia as part of a funeral procession to protest the pending demolition of the Birks Building.

Angus McIntyre photo

And just like that, the beautiful old Birks Building—well not that old, really: it was only sixty-one in 1974—was killed off to make way for the Scotia Tower and Vancouver Centre Mall. For a long time afterward, a large RIP banner hung in the window of a second-storey office in the Sam Kee Building on Pender Street.

The only positive thing to come out of the loss of this much-loved building was that it mobilized Vancouver’s heritage preservation community, who pressured city council to request heritage protection powers from the provincial government. This move saved many of the city’s other fine historic structures—including the Orpheum Theatre, Hudson’s Bay, Waterfront Station, the Hotel Vancouver and the Marine Building—from a similar fate.

In the 1970s, the Scotia Tower and Vancouver Centre development took out the Strand Theatre and the iconic Birks Building, an eleven-storey Edwardian edifice where generations of Vancouverites met under the clock.

Vancouver Archives Str N201.1, 1924

PACIFIC CENTRE

When I moved to Vancouver from Australia in the mid-1980s, locals had already had a dozen years to get used to Pacific Centre and the “Great White Urinal”—the name they’d not so affectionately bestowed upon the Eaton’s department store building. But it wasn’t until several years ago when I saw a 1924 photo showing the Strand Theatre, the Birks Building and the second Hotel Vancouver lined up along Georgia at Granville, that I realized how much we had lost.

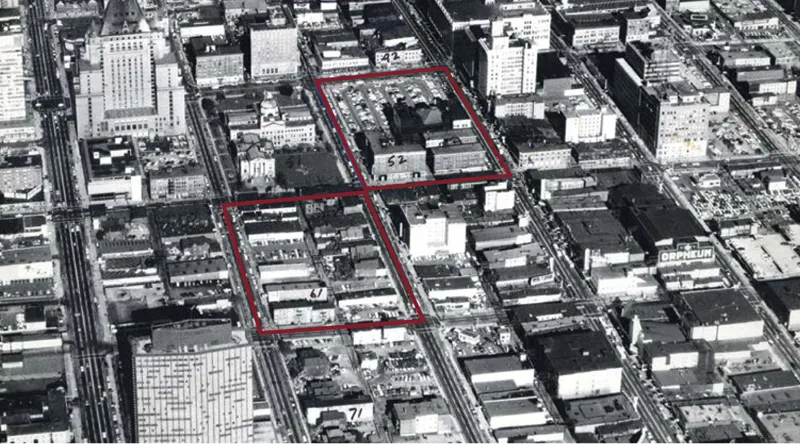

In the 1960s, the pro-development city council sought to launch a significant redevelopment of downtown Vancouver, with the intersection of Georgia and Granville Streets as the epicentre of this change. Many feared that the downtown core would lose business to the malls that were opening in the suburbs, and the hope was that a new, modern shopping centre would attract people to breathe life back into that intersection. This retail vibrancy would come, they believed, through a new and improved superblock and underground parking that spread across several blocks. The superblock was made up of Block 52—bounded by Granville, Georgia, Howe and Robson—and Block 42—bounded by Granville, Georgia, Howe and Dunsmuir. The problem was that the T. Eaton Company, which owned all of Block 52, didn’t seem in a hurry to move their department store from its location on West Hastings Street (currently the SFU Harbour Centre building), and a new Eaton’s was essential to anchor the proposed shopping mall. The other problem was that Block 42 was owned by eighteen individual landowners, and none of them wanted to sell. By the fifth redevelopment report in July 1964, a frustrated Mayor William Rathie and members of city council were trying to figure out ways they could expropriate the land from the unwilling owners.

Angus McIntyre got this shot in 1974 by leaning out of an open arched window on the top floor of the Birks Building. The Granville Mall was under construction, and Eaton’s had just opened.

Angus McIntyre photo

The newly bulldozed Block 42 in 1973 and the thirtystorey TD Tower replaced the parking lot that had replaced the second Hotel Vancouver in 1949, and Eaton’s built a five-storey store. In 1981, Eaton’s added another two floors. Later, the store became a Sears and, since 2015, has been a Nordstrom, a high-end American department store.

Vancouver Archives 23-24

In May 1968, the city held a plebiscite to allow them to buy up all the properties in Block 42, and seventy percent of voters agreed. The subsequent mayor, Tom Campbell, told the press: “We’ve got a united city which wants a heart. Vancouver had only a past—today it has a future. This is Vancouver’s greatest day.”1

By 1974, the city had the Pacific Centre and Vancouver Centre shopping malls, much of it as an underground bunker. We’d rid the streets of grand old brick buildings and gained the IBM Tower, the former Four Seasons Hotel, the Scotia Tower and a thirty-storey black glass monument to capitalism in the TD Tower. Rather than revitalize the Granville and Georgia intersection, we had sucked the life right out of it.

An aerial view showing the future site of Eaton Centre, Pacific Centre and Robson Square, ca. 1963.

Vancouver Archives 515-32

BLOCK 52

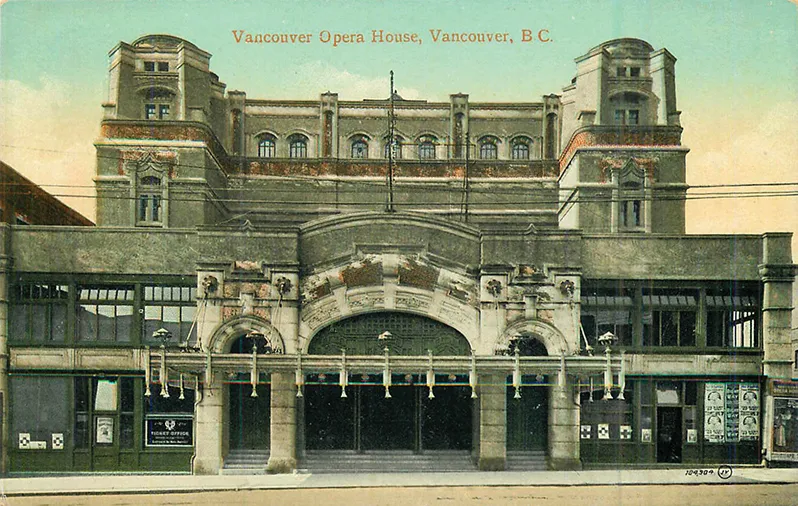

Vancouver Opera House (1892–1969).

Tom Carter collection, 1903

Granville Mansions (1905–69).

Vancouver Archives 586-7015, 1948

Second Hotel Vancouver (1916–49).

Vancouver Archives 586-7022, 1948

York Hotel (1911–69).

Vancouver Archives 99-3996, 1931

BLOCK 42

After the City of Vancouver declined to buy the park on the northwest corner of Georgia and Granville for $17,000, the Canadian Pacific Railway sold the lot to developers Benjamin Johnston and Samuel Howe who built the three-storey Johnston-Howe Block in 1901 and promptly flipped it for $1 million the following year....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Downtown

- Downtown Eastside

- West End

- West of Main Street

- East of Main Street

- North Vancouver

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Vancouver Exposed by Eve Lazarus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Crescita personale & Storia nordamericana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.