1

GREAT FEMALE ARTISTS OF THE AVANT-GARDE: FROM EMBROIDERY TO THE REVOLUTION

Natalia Murray

Women artists of the Russian Revolution were brave, bold, immensely creative, provocative and free. Their role in building the new art of the new Bolshevik Russia is hard to overestimate. Described in 1913 by the Social Democratic feminist, Alexandra Kollontai, as ‘gainfully employed, self-confident, ambitious’, they were ‘the centre of their own dramas, not the object of men’s’.

However, their leading role in the development of Russian art was not itself established by the Revolution. In 1883 Andrei Somov, curator of paintings at the Hermitage museum in St Petersburg, had published an article dedicated to the ‘phenomenon’ of nineteenth-century Russian women painters and engravers; in his 1903 history of Russian art, Alexei Novitsky included a special section on Russian womenartists; and in 1910 the St Petersburg journal Apollon organised an exhibition of Russian female artists. Their artistic input was discussed in the Russian press and at public lectures.

One of the reasons for the cultural prominence of female artists rests in the early availability of artistic education to women. The Imperial Academy of Arts in St Petersburg began to admit women students as early as 1871, and soon the more liberal Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture followed suit. As a result, the first generation of professional women artists was already formed in Russia by the 1880s. In addition to established institutions, private art courses were offered to women from the 1870s and in 1911 female graduates in St Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Kazan were allowed to sit for state examinations. By 1914 women constituted 30 percent of students in institutions of higher education.

Although the best training in fine arts was available to women by the nineteenth century, it was the Arts and Crafts movement that gave most encouragement to female artists and entrepreneurs. According to the historian Wendy Salmond, ‘the new aestheticized folk art perfectly represented women’s own position between tradition and change. It also provided the conduit to women artists’ engagement with Modernism.’

The process of establishing female crafts and promoting textiles as bearers of identity by women involved collecting artefacts associated with women and their pastimes, displaying them at home or at private museums, organising and patronising the embroidery, lacemaking and other workshops for peasant women, popularising those artefacts via printed editions and publishing ethnographic commentaries that reflected on these female pastimes, material culture and crafts.

The first folk art revival workshop, which encouraged the development of the neo-Russian style, was established by Elizaveta Mamontova. In 1876 she opened a joinery workshop on the Abramtsevo estate and employed the artist Elena Polenova, who not only trained the artisans in traditional crafts but left her mark in modernising handicrafts and building a platform for the next generation of avant-garde artists.

Mamontova’s initiative was followed by the Talashkino workshops founded and financed by Princess Maria Tenisheva. This establishment included an embroidery workshop and experimented with reviving the authentic methods of dyeing fabrics with natural dyes. Another well-known enterprise was the Solomenko workshop in Tambov Province, organised in 1891 by Maria Iakunchikova. Abramtsevo, Talashkino and Solomenko not only encouraged the peasant crafts revival, but also functioned as experimental laboratories for the modern artists inspired by folk arts.

The important role of women in resurrecting traditional arts and crafts encouraged one of the most influential nineteenth-century art critics, Vladimir Stasov, to assume, perhaps unfortunately, that the engagement of women collectors in gathering embroideries, needlework and textiles was ‘gender-appropriate’ and that women should therefore focus on the female arts and crafts only. Thus, when the future propagator of avant-garde design, Natalia Davydova, approached Stasov to seek advice on how to write a history of Russian art, he discouraged her and advised her to write a history of Russian lace instead. Davydova followed the art critic’s advice and in 1900 founded an embroidery workshop in Verbovka in her native Ukraine. Here she employed thirty peasant women, who were encouraged to resurrect traditional designs and to adapt them to twentieth-century fashion.

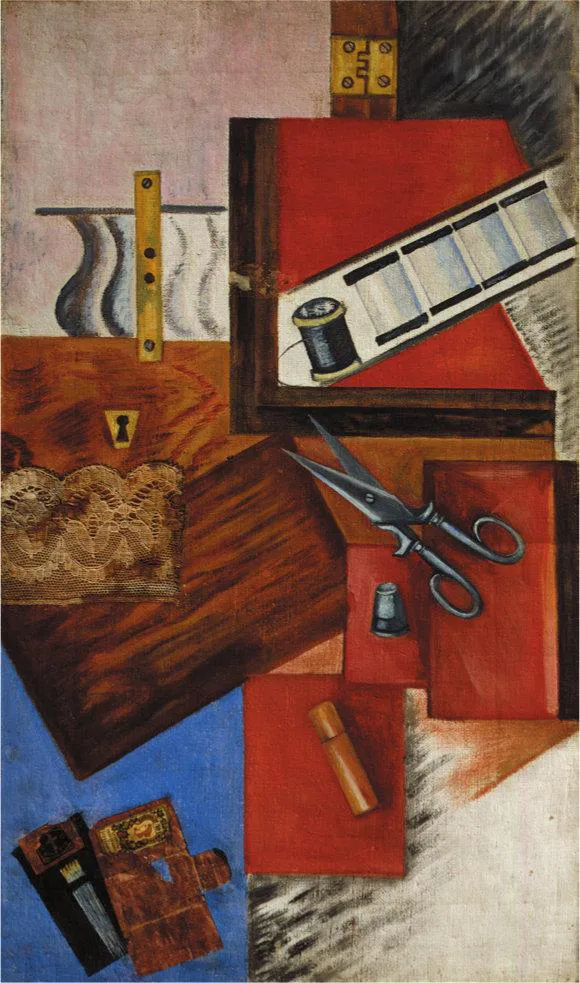

In 1906 Davydova met a future star of the Russian avant-garde, Alexandra Exter, at the Kiev Art Institute (Kyivske Khudozhnie Uchylyshche), where they combined their studies with expeditions to Ukrainian villages, exploring and collecting examples of traditional embroidery. This material would be then used by peasants who worked at Verbovka and who were encouraged not only to copy but to modernise the traditional designs. At the same time Davydova and Exter took an active part in the organisation of the Exhibition of Applied and Handicraft Arts, which opened in 1906 at the Emperor Nicholas II Museum in Kiev. Here Exter used for the first time an experimental method of exhibiting carpets and embroidery: by combining various geometrical patterns together she would create new designs and geometric rhythms. As one of Exter’s main biographers observed, ‘These were her first experiments in creating abstract compositions. At least in the series of Exter’s Colour Dynamics executed in late 1910 it is not difficult to see several plastic approaches, which were first intuitively tried by the artist in the Exhibition of Applied and Handicraft Arts’.

After graduating from the Kiev Art Institute and getting married to a successful lawyer, Exter travelled to Paris where she studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and became a friend of Guillaume Apollinaire, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and Ardengo Soffici. Familiar with the latest artistic innovations in Paris, Exter was often responsible for the Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde’s almost instantaneous information about the contents of the most recent Paris shows, or about the latest discussions on Cubism.

In November 1908 Exter joined another leading avant-garde woman artist, Natalia Goncharova, in an exhibition of work by young Ukrainian and Russian artists called Zveno (The Link), which opened with great aplomb in Kiev. At this exhibition, for the first time, works by Goncharova were shown next to those of Exter, and here eleven other women artists were also represented alongside their more famous male colleagues. The group from St Petersburg was led by Liudmila Burliuk, and included Agnessa Lindeman and Erna Deters, already recognised for their Art Nouveau embroidery, a sculptor Natalia Gippius and another graduate of the Kiev Art Institute, Evgeniia Pribylskaia. Like Davydova and Exter, Pribylskaia directed arts and crafts workshops in the Ukrainian village of Skopstsy, reviving traditional patterns and producing new designs. Her work gained full recognition after the Revolution, when she was entrusted with the organisation of the crafts section at the Russian Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris.

In the Zveno exhibition Exter showed still lifes and Western European landscapes next to embroidery: a trend that she followed in several subsequent exhibitions. Her works at Zveno attracted the attention of art critics but her extraordinary sensitivity to colour seemed to some to be too sophisticated for a woman artist. Thus a critic Savenko lamented in his review of the exhibition: ‘Mr Exter has daubed his canvas with unrelieved blue paint, the right corner with green, and signed his name.’

However, even if the often patriarchal Russian society was not ready to accept the dynamic presence of women in Russia in all fields of art and science at the beginning of the twentieth century, there was an innovative and radical approach in the sphere of demands for social equality. Even early in their lives and careers women artists were far from untravelled provincial young ladies. Predominantly middle class, they not only knew each other, but were united by a common purpose, supported and inspired one another, and developed into mature artists. They formed an intense and energetic group. They attended and took part in radical exhibitions in Kiev, Moscow and St Petersburg, read the latest journals, and studied Post-Impression...