- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The 'Three Colours' Trilogy

About this book

This appreciative account of the 'Three Colours' trilogy communicates the power and imagery of the films, and demonstrates how Kieslowski's art is brought to bear in their moving renditions of the lives of its characters. An interview with Kieslowsi shortly before his death concludes this tribute.

Information

1 Before the Trilogy

Krzysztof Kieślowski was born in Warsaw in June 1941, the beginning of an unsettled childhood, not only because of the war and its aftermath but because his father suffered from tuberculosis, forcing the family to travel from one sanatorium town to another. Krzysztof sometimes changed school several times a year, but he performed well academically, though he found school of little value. Because he too had poor lungs, he spent a lot of time at home reading, and it was through books, he later claimed, that he realised ‘there was something more to life than material things which you can touch or buy in shops’.2

At the age of sixteen, Kieślowski trained for three months as a fireman, but, partly to avoid military service, he returned to his studies at Warsaw’s College for Theatre Technicians, where he fell in love with the theatre. Since it was impossible to become a stage director without qualifications in higher education, he then applied to the Łodz Film School; only on his third attempt did he succeed, by which time he was no longer interested in pursuing a theatrical career. Nevertheless, he enjoyed his four years at Łodz, watching and discussing films, and making both features and documentaries.

It was during this period that Kieślowski developed an interest in politics; in 1968, just before graduating, he took part in a student strike. Such activities, however, were hardly uncommon at that time, especially in Poland, where from 1968 onwards the Communist Party steadily reversed the slow, tentative progress towards greater personal, public and artistic freedom that had begun under Wladyslaw Gomulka. The post-’68 period of civil unrest, food shortages and widespread disillusionment, resulted in the rise of an uncensored underground press and ‘The Flying University’, which held lectures, discussions and other cultural gatherings in private houses; it was also a time when documentaries achieved an unprecedented popularity, purporting to show the realities of life as experienced by ordinary Poles, as opposed to the falsifications of Party propaganda. On graduating from film school, therefore, it seemed natural to Kieślowski to begin his professional film-making career as a documentarist.

Given the pervasive presence of politics in Polish life under the repressive Edward Gierek, it was perhaps inevitable that many of Kieślowski’s documentaries concerned people working for, or fighting against, State institutions: Factory (Fabryka, 1970) alternated scenes of workers at the Ursus tractor factory with a management board meeting about the plant’s inability to meet its production quota; Workers ’71 (Robotnicy ’71, 1972) was an attempt ‘to portray the workers’ state of mind’3 after the strikes of 1970 and the downfall of Gomulka; Hospital (Szpital, 1976) charted the determination of orthopaedic surgeons on a 32-hour shift to overcome dismal working conditions; and From a Night Porter’s Point of View (Z Punktu Widzenia Nocnego Portiera, 1977) was a portrait of a fanatically right-wing, disciplinarian factory porter. Despite, however, the often controversial nature of Kieślowski’s subject matter and approach (which resulted in some of his films being shelved for years) and the fact that in the late 1970s he became involved, as vice-president to Andrzej Wajda, in the struggles of the Polish Film-Makers’ Association for greater artistic freedom (‘We were completely insignificant,’ he told Danusia Stok),4 Kieślowski later insisted that his documentaries had been intended not as examinations of repressive political institutions but as portraits of individuals made from a humanistic point of view.

And indeed, there is some justification for this claim. While From a Night Porter’s Point of View does, through its gentle mockery of the porter’s extreme, conservative views on crime, punishment and authority, have clear social, political and ethical implications, it is at the same time primarily a (surprisingly sympathetic) character study of a rather sad and unfulfilled man. Likewise, if Talking Heads (Gadające Głowy, 1980), which asks seventy-nine Poles when they were born, what they do, and what they would most like, offers tantalising insights into the nature of contemporary Polish society, it also, by moving in quick linear fashion from the youngest to the oldest interviewee, becomes a universally applicable essay on the emotional, physical and psychological effects of ageing. One senses that, even at this stage in his career, whatever interest Kieslowski had in the world of politics derived largely from his fascination with its effects upon the individual. Increasingly, however, he came to feel that this fundamentally humanist fascination was ill served by documentary: the very process of making documentaries, because it invaded people’s privacy, prevented him from getting as close to the heart of personal experience as he wanted, while actors, in fiction film, might allow him greater access to the realm of people’s inner lives.

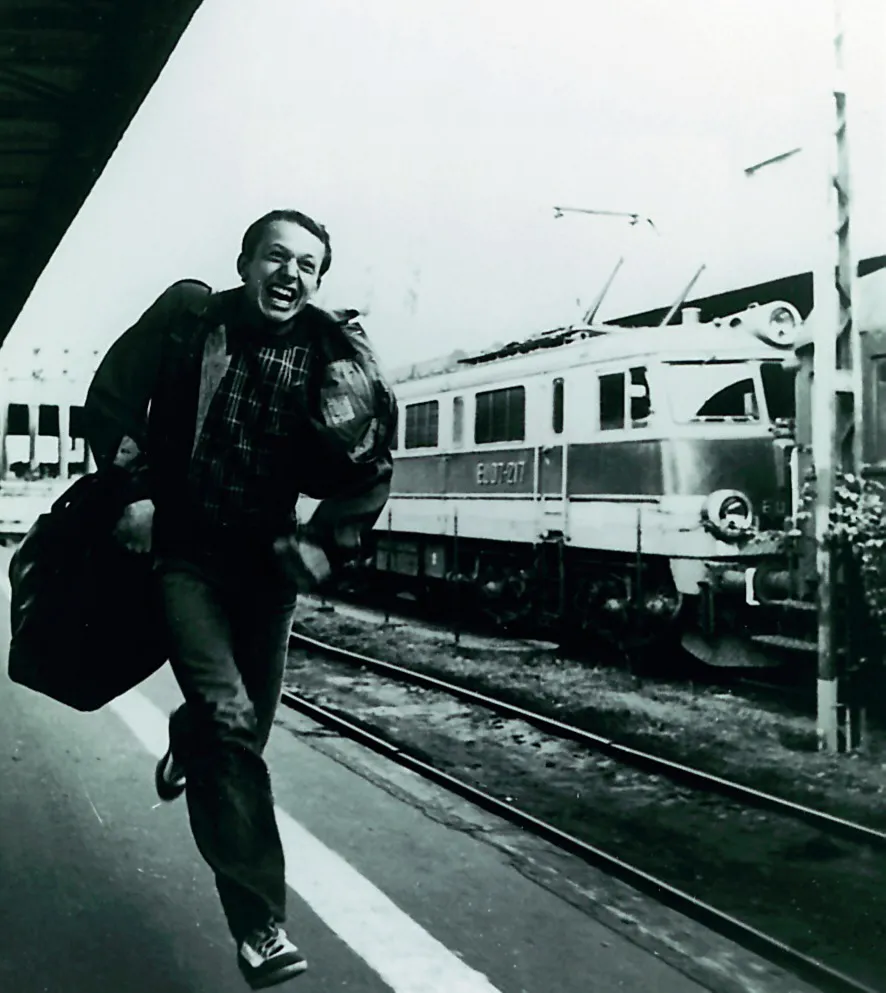

‘What if …?’: Blind Chance, a film in the conditional mood

After General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s clampdown on the free trade union Solidarity and the introduction of martial law in December 1981, Kieślowski seems to have become increasingly disillusioned with politics. By this time, he had virtually abandoned documentary work for fiction features, achieving his first international success with Camera Buff (Amator, 1979), a droll satire in which a man’s progress from shooting home-movies of his family to making documentaries about and for the factory where he works brings him into conflict with his censorious bosses. Clearly, there was more than a hint of political comment here, as there would be in Blind Chance (Przypadek, 1981), in which a medical student runs to catch a train, with three potentially different outcomes: he catches it, falls in with a Communist and becomes a Party activist (resulting in his betrayal of a girlfriend); he crashes into a station guard who, by having him arrested and brought to trial, inadvertently drives him to join the militant underground; or he misses it, bumps into a lover he later marries, completes his studies with considerable success, ignores politics and finally, sent abroad on a trip that is the crowning point of his career to date, dies in a plane crash. Again, the various options of political life in Poland determine the film’s subject matter, although Kieślowski himself saw it as ‘no longer a description of the outside world but rather of the inner world’.5 Certainly, it’s impossible to ignore certain crucial, non-political, philosophical elements – crossed wires, interwoven lives, the mysterious, cruelly ironic workings of fate and chance, the narrative’s ‘conditional’ mood of ‘what if?’, all which occur, with increasing frequency and sophistication, in his later work.

Thus, in No End (Bez Końca, 1984), the widow of a lawyer, who at the time of his death was preparing to defend a victim of martial law, gradually becomes involved in the struggle to save the young worker from the authorities; her actions, however, are less the result of growing political commitment than of her being prompted, as it were, by her husband’s ghost who, mostly unseen except by the audience, watches over her in her solitude. While the film offers a lucid account of how self-serving bureaucracy and an embattled judiciary make for political and moral compromise (‘Martial law was really a defeat for everyone,’ Kieślowski told Stok),6 the director was equally fascinated by the metaphysical and emotional aspects of the story. The film ends with the widow, unable to bear her grief any longer, committing suicide so that she may be reunited with her beloved husband. Politically the film may be despairing, even defeatist, but on a humanistic level, its conclusion, with wife and husband united once more in a world Kieślowski regarded as ‘a little better than the one in which we’re immersed’, is one of transcendent devotion.

Living with ghosts: Grażyna Szapolowska in No End

It was while preparing No End that Kieślowski first embarked on what would become an enduring collaborative partnership with Krzysztof Piesiewicz, a lawyer he met while making a documentary on trials under martial law. (The film was never completed, since Kieślowski found that his camera’s presence in the courtrooms seemed to encourage judges to pass unusually lenient sentences, which therefore mitigated against the accuracy of his film!) Because the director felt himself ignorant of court procedure, he invited Piesiewicz to help with the legal details in the script of No End; the partnership worked so well that they revived their collaboration for Kieślowski’s subsequent The Decalogue (Dekalog, 1988), a ten-part series made for Polish television after Piesiewicz suggested the director consider a film about the Ten Commandments and their relevance to the modern world.

Originally, Kieślowski’s intention was to write the ten episodes – two of which were shot in alternative longer versions (as A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love) for cinema release – and then hand them over to ten young, first-time film-makers at the Tor Production House (which Kieślowski was running as deputy to Krzysztof Zanussi). By the time the scripts had reached the first-draft stage, however, Kieślowski liked them so much that he decided to direct them himself (though he did select nine different cameramen for the ten episodes). The result was one of the most impressive achievements in modern film-making. Keeping the political realities of contemporary Polish life in the background, the aim was to focus on the ‘internal lives’ of the various protagonists – all inhabitants of a Warsaw housing estate – as they made their ‘concrete everyday decisions’ about various ethical and emotional dilemmas associated in one way or another with the Commandments. Characteristically, Kieślowski refrained from offering simplistic, moralistic comments on what he felt was right or wrong; instead, rather like Eric Rohmer’s series of Contes moraux, the films were cool, pragmatic studies of the problems faced by people who ‘don’t really know why they are living’;7 people who feel lonely and uncertain about particular aspects of their lives, and want to achieve some sense of happiness, of belonging, of having done their best with regard to what is ‘right’ for them. Inevitably, given Kieślowski’s self-confessed pessimism, they often fail, or if they succeed, it is usually at a painful price. Besides being a magnum opus in its own right, The Decalogue is also, as we shall see later, of considerable interest for the way in which it anticipates in many respects aspects of the Three Colours trilogy: most notably, perhaps, the accent on loneliness and dysfunctional families; the importance of love; and the way in which Kieślowski’s narrative forges strange, unexpected connections between different characters.

A Short Film About Killing

Soul sister: Irène Jacob in The Double Life of Véronique

Kieślowski’s next film, again written with Piesiewicz, took him still further away from the specifically Polish experience, not only in that it was his first international co-production, but because its subject matter is perhaps best described as spiritual. The Double Life of Véronique (La Double vie de Véronique/Podwójne Życie Weroniki, 1991) concerns the strange, mysterious links between the lives of two physically identical young women born at the same time on the same day: the Polish Weronika, a budding soprano with a weak heart and an indecisive attitude towards her lover, ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Interpreting the Trilogy

- 1. Before the Trilogy

- 2. Making the Trilogy

- 3. Three Colours: Blue

- 4. Three Colours: White

- 5. Three Colours: Red

- 6. The Trilogy: Connections

- 7. The Trilogy: Reflections

- 8. The Trilogy: Coda

- 9. Elegy: Remembering Kieślowski

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The 'Three Colours' Trilogy by Geoff Andrew in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Film e video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.