![]()

CHAPTER 1

ON BEING MUSLIM IN BAZAAR-KORGON

The townscape of Bazaar-Korgon is low and sprawling. Walking, it takes at least an hour and a half to traverse the town. In most quarters earthen walls line dusty streets, creating a landscape that, to the unfamiliar eye, becomes a maze of identical roads. The glare of a midday summer sun blinds those who dare venture out in the heat that tops 40 degrees Celsius. At the right time of day, however, nearly all the year through (winters being mild out of doors in the sun but bone-chilling in an unheated room) the streets are alive with activity. Women and girls gather at public water sources, socializing while they wait to fill their buckets. Groups of young men and boys stand or crouch on corners and other points along the roadside, not waiting for anything in particular, just talking and passing time. Few residents own cars, so most walk, stopping along their way to greet friends, neighbors, relatives, or acquaintances; the demands of this kind of everyday sociability make an already long walk even longer.

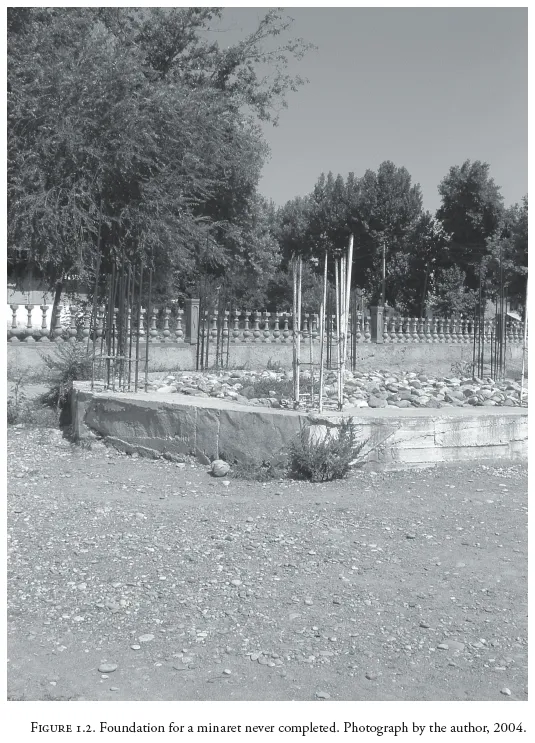

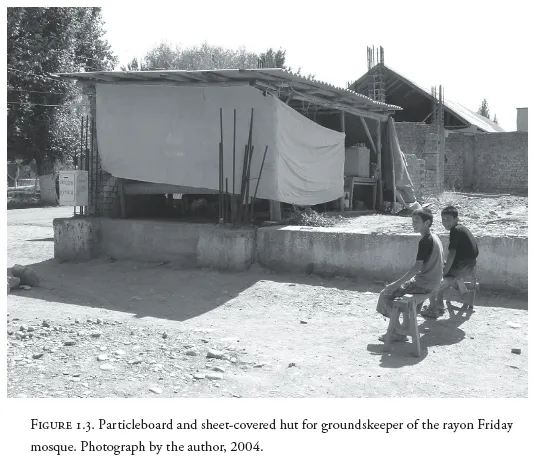

Five wide, paved streets cut through Bazaar-Korgon. On one of these lies the current town square, where one of the town’s two Lenin statues stands. On the southwest edge of the square, on the hill overlooking the bazaar is the district Friday mosque. Close inspection reveals that the wider mosque complex is incomplete; one sees the foundation for a minaret never built, the makeshift facilities for ritual ablutions, the groundskeeper’s flimsy hut, two of its walls consisting merely of a sheet.

The construction of the central mosque, begun in 1993 and completed in 1999, was nearly universally supported by townsfolk. Perhaps this unanimity was because during the 1990s, when all else was falling apart in town, it was the one concrete sign that postsocialist dreams might be realized. This particular project was important because its realization, involving foreign donors, symbolized successful participation in new political and economic arenas. It was also an expression of newly gained religious freedom and the ability to assert oneself as Muslim in public. The mosque was “the transition” to capitalism and democracy happening; through it, residents imagined that the dream of transition might still be fulfilled, despite the massive economic downturn of the early post-Soviet years. Its construction even moved forward through the mid- to late 1990s, when Kyrgyzstan’s economic decline reached its nadir.

Just to the northwest of the mosque is the bazaar. It too was emblematic of the transition.1 In the Soviet period there had been some light industry in town and a series of other state-run enterprises, but most residents had been engaged in agriculture. The town had basically been two large state farms. The closure of the factories, the cessation of collective farming, and the distribution of agricultural land among residents in the early 1990s left large portions of the population unemployed. With no other jobs in sight, countless townsfolk and residents from villages in the region tried their luck in the new marketplace—as petty merchants in the bazaar. Sadly, most were not able to reach the state of affluence they equated with democracy and capitalism. In fact, most remained impoverished.

If the bazaar failed to fulfill the economic promises of capitalist dreams, it faired better in providing for the realization of other liberal promises—freedom of conscience, press, and assembly. The bazaar had become a place to produce, sell, and consume ideas in the form of books, pamphlets, audiocassettes, and CDs. It was also a major node of social interaction and a location where those wanting to get a message across could advertise. And while these advertisements generally concerned new products or the announcement of events, the public space of the market had also served as a venue for conveying Islamic messages.

There is a story that sometime in the year 2000 men stood in front of the bazaar and called listeners to come “close to Islam” (dinge jakyn). None of my acquaintances could say who the men were, but gossip was that they were “Wahhabis” or members of Hizb ut-Tahrir.2 The veracity of this evaluation is suspect, but what is interesting is the impression this event made on residents; the story was retold to me many times as evidence of what was happening in Bazaar-Korgon. Other indicators of change offered to me were the new ways women were wearing headscarves and the increasing number of women doing so. Residents also pointed to the rising number of men, especially young boys, attending mosques, and they mentioned the home-based Islamic study groups that had proliferated in town. Unlike the construction of the central mosque, however, these displays of Islamic behavior were not as positively evaluated.

Residents of the community read these signs as indicators that the actors adhered to interpretations of Islam and held conceptions of Muslimness (muslumanchylyk) at variance with the public norms of the late Soviet and early post-Soviet era. This challenge stirred debate in the community, especially among those who did not refer to themselves as “close to Islam” but who considered themselves Muslim nonetheless. What did it mean to be a Muslim in Bazaar-Korgon at the turn of the millennium? This book is premised on the idea that the answer to this question was up for debate; the hyperinterrogation of this notion—the fearful attitude displayed by some and the playful shaping of it by others—was in fact the most salient aspect of religious life and of discussions about religion in the community.3 The space for this debate is what made religious life in turn-of-the-millennium Kyrgyzstan so unique, compared to, for example, neighboring Uzbekistan (Rasanayagam 2006c) or the situation in the Soviet period. This book is about these discussions.

However, this assertion does not mean that religious life per se was what was most pressing in the lives of Bazaar-Korgonians at the turn of millennium. For most residents, dealing with the economic and social dislocations of the postsocialist period was the most urgent issue. Kyrgyzstan’s economic decline reached its nadir in 1998. By 2003, when the research for this project started, residents were still climbing out of that spiral and were just barely beginning to meet their daily needs (see Reeves 2012, 108–9). Yet the ability to feel “normal” and the ability to return to some sort of familiarity or regularity (see Zigon 2009) in the everyday workings of the new political, economic, and social situation were still far off. Joma Nazpary (2002, 1–19) has discussed this period in Kazakhstan in terms of “chaos,” while Caroline Humphrey (2002, xvii) has employed the term “radical uncertainty” for the Russian situation. In 2003 and 2004, residents of Bazaar-Korgon were living in this chaotic, uncertain time and looking back to the Soviet period was a ubiquitous activity. It was a consciously “post” environment.4 It was no different for those who were actively engaged in learning about or being close to Islam. The insecurity and uncertainty of postsocialist life was the primary terrain in which all residents of the town lived.

What does it mean to be a Muslim in Bazaar-Korgon? This chapter address that question. It starts, however, with a discussion not of religion but of the economy, society, and politics. For most residents, dealing with the economic, social, and political dislocations of the postsocialist period was their primary concern; interrogating religion was at best secondary. But there were some in the community for whom religion was of central importance—those who were “interested in Islam.” The chapter moves to a discussion of such individuals and what kinds of debates their modes of understanding and living Islam sparked.

Small-Town Hardships

In 2004, Bazaar-Korgon was administratively classified as a village, despite the fact that approximately thirty thousand people inhabited the community. There were few paved roads. Most inhabitants did not having running water in their homes. There were only a handful of businesses, and they employed no more than thirty persons on average, with the exception of an ice-cream company with one hundred workers. Despite this village character, it was the capital of the rayon (an administrative unit or district).5 Paid work was scarce. The vast majority of residents were either employed in the state sector (education, health care, and government offices), worked in the bazaar, or engaged in agricultural work. When the two collective farms were divided up after the Soviet breakup, nearly everyone received a piece of land, located just outside town, which today provides supplemental income either through the sale of crops or the rent and/or sale of the land. Moreover, the majority of people had small bits of land at their residences on which to grow fruit and vegetables for household consumption.

The older part of the town, at least according to local oral history, dates back more than two hundred years. Few families living there at the time of this research, however, could trace their lineage back to the early days of the community. Those who could claimed to know which cities in contemporary Uzbekistan their families had left in order to found and settle in Bazaar-Korgon. The population was approximately 80 percent Uzbek and 20 percent Kyrgyz. In terms of trading, social networks, and cultural linkages, residents had long looked to the urban centers of the south and west—contemporary Uzbekistan or Uzbek-dominated regions of Kyrgyzstan—rather than to the mountains of the north and east. This orientation remained in place after republican boundaries were drawn in the early twentieth century and the town of Bazaar-Korgon became part of the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic. Ties with Uzbekistan remained strong throughout the Soviet and early post-Soviet periods partly because of the highly porous border. The situation did not change until 1999, when Islam Karimov, the president of Uzbekistan, sealed the border following an assassination attempt by unknown assailants. The growing influence of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), including their kidnappings of foreigners on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border and their desire to topple the Karimov regime, aggravated by what Uzbekistan saw as weak Kyrgyzstani antiterrorism efforts and ineffective border patrol, provided further impetus for Karimov to seal the border (Megoran 2002). After this closure, trading and social networks became more difficult to maintain.

Bazaar-Korgon is in the Fergana Valley, thirty kilometers east of the Uzbek border, twenty kilometers west of its oblast (province) capital, Jalal-Abad, and just off the main highway that connects Bishkek and Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s largest and second-largest cities, respectively. While the town of Bazaar-Korgon is predominantly Uzbek, Bazaar-Korgon rayon is inversely dominated by Kyrgyz. The ethnic makeup of the rayon reflects the Kyrgyz-Uzbek ratio of the country. The Fergana Valley has been the site of major sedentary populations of Central Asia since antiquity. Contemporary Uzbeks assert the most forceful claim as primary descendants of these populations, despite the long-standing heterogeneity of the region’s peoples (see Schoeberlein-Engel 1994; Finke 2014). Prior to Soviet modernization campaigns of the early twentieth century, which included a massive project of forced settlement, the contemporary Kyrgyz population was nomadic. During the Russian imperialist period and the Soviet era, Russians and then others from around the Soviet Union settled in Kyrgyzstan. Following the Soviet collapse, most of these newer residents fled. Only a handful of what once was a significant Slavic population in Bazaar-Korgon (approximately 10 percent of the total) from the 1970s to the early 1990s remained at the time of research. There are two official languages in Kyrgyzstan—Kyrgyz and Russian. Uzbek is not an official language, though it is the language of instruction in many schools of southern Kyrgyzstan. In Bazaar-Korgon, for example, four out of seven schools use Uzbek as a language of instruction and follow the curriculum used in Uzbekistan, though with the addition of courses in Kyrgyz language and the history of Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyz residents of the north often note the heavy influence of the Uzbek language on the Kyrgyz spoken by southerners.

Ethnonational identity is an important issue in Kyrgyzstan, not least because of the sizable Uzbek population. During the Osh riots of 1990, 120 Uzbeks and 50 Kyrgyz were killed during three days of ethnic violence sparked by land disputes, the uneven distribution of power, and high levels of unemployment (Tishkov 1995, 134). In the first decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan seemed to prosper while Kyrgyzstan lay in misery. This differential led many Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan to look longingly toward Uzbekistan. For many, Karimov typified the strong leader Central Asians thought they needed to pull them through the difficulties of the early post-Soviet period. The early economic success of Uzbekistan seemed to confirm this idea. Yet, by the turn of the millennium, the situation had been nearly reversed. Many Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan began to perceive the Karimov administration as increasingly authoritarian. Moreover, they expressed satisfaction with the freedom they enjoyed in Kyrgyzstan to grow, sell, or manufacture what they wanted and when, in contrast to the centrally controlled Uzbek economy (see Liu 2012, 9). They saw Uzbeks across the border experience a sharp decrease in living standards as well as a curtailment of freedoms, including freedom of expression and conscience. The Andijan massacre of 2005, in which several hundred people were slaughtered by the Karimov government, confirmed what locals knew and human rights organizations had feared—the authoritarian regime would use any means to maintain control, including torture, kidnapping, arrest, and mass killings (Human Rights Watch 2005; International Crisis Group 2005). Many of those who fled the 2005 massacre landed in Bazaar-Korgon rayon.

For many Uzbeks at the turn of the millennium, Kyrgyzstan was a place of relative freedom. Those I spoke with in Bazaar-Korgon celebrated their independence, which their friends, families, and business partners in Uzbekistan did not have. Yet, when compared to Kyrgyz people in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbeks often felt less than equal, despite full citizenship and equal rights guaranteed by law (Khamidov 2002). Uzbeks and Kyrgyz were in agreement, however, concerning Kyrgyzstan’s poor economic growth and the rampant corruption in politics and business. In March 2005, the Tulip Revolution took place, ousting President Askar Akaev, who had been in office since 1991. While many hoped the revolution would signal a changing political and economic environment, the cronyism and corruption of the former regime continued. Economic conditions, too, remained bleak (Sershen 2007), a persistent situation that by 2010 played a role in a second political upheaval. Tragically, massive ethnic violence followed quickly on the heels of these political shifts.6 In June 2010, some 400 people were killed, nearly 2,000 were treated for injuries, and approximately 300,000 people were displaced, with about 111,000 fleeing to Uzbekistan during three days of violence in southern Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyzstan Inquiry Commission 2011; Human Rights Watch 2010). Bazaar-Korgon was at the center of this violence (McBrien 2011, 2013). This tumult, however, was not even imagined in 2003–4 when I conducted my research.

At that time what was crucial for day-to-day living was economic survival and reorienting oneself within rapidly shifting economic and political environments (see Creed 2002). With few businesses or factories in town, work was found in one of three arenas—the field, the bazaar, or the government. For most, in order to maintain an average income that would feed and clothe a family, provide a comfortable home, and leave enough for small luxuries like televisions, radios, cell phones, and hosting guests at small parties, work in all these sectors had to be combined. When I asked an agricultural specialist from the rayon government what percentage of the population was involved in agricultural work, he replied, “Everyone.”

His answer was not in jest. The land that had belonged to the collective farms had been divided among town residents regardless of whether they had worked there. The amount of land allotted was based on family size. The average allotment was between fifty and sixty-five sotik.7 In theory everyone was to receive a piece. In practice the land was doled out more quickly to those close to power and those who had worked the land. Others had to fight for their parcels. Interestingly, some of these fights came a decade after the dissolution of the union. In the early 1990s, many professionals—teachers, doctors, and administrators (the majority of whom were Kyrgyz)—imagined that the economic downturn would be temporary. They were not farmers but professionals, they lived in apartments, and land seemed unimportant. Only after the reality of the economic situation set in did many of these people assert their right to the land parcels. One couple, for example, two physicians in their fifties, received their parcel in 2004. The land closer to town having already been given away, they received their fifty-five sotik (0.55 hectare) on an edge of town that was more than an hour’s walk from their home.

Inconveniences like an hour’s walk didn’t stop residents from cultivating cash crops.8 The parcels of land had become extremely important for income generation, and great effort was put into their cultivation. In the household surveys I conducted, I found that for those families who had one or two adults employed as schoolteachers, taxi drivers, bazaar merchants, or civil servants and bureaucrats, the revenue they received from their land still made up at least 50 percent of their total income for the year. These people were generally perceived by their neighbors as being average in economic terms. The rich, of whom there were few, found their money in the same places. They just had a bit more land—usually two hectares or more—had bigger, more successful stalls at the bazaar, or were higher-level bureaucrats. One of the most important means of additional income for household budgets was the money brought in by circular migration. Paid work was not only hard to find in town; its absence was a chronic national problem. Large numbers of Bazaar-Korgonians sought work abroad, primarily in Russia, though there were some from the town working in Turkey and the European Union as well. Residents who migrated to Russia worked primarily as manual laborers and merchants. This trend would dramatically increase over the next decade. In 2013, Kyrgyzstan was third in the World Bank’s rankings of countries dependent on remittances, with one-fifth of its workforce employed as migrant laborers (Economist 2013).9

In 2004, the average Kyrgyz household was much smaller than an Uzbek one. This was partly because the Kyrgyz living in town had moved there relatively recently, leaving their extended families in their villages of origin. Their households consisted of the nuclear members alone, generally two parents and three children. However, extended family members regularly visited, and it wasn’t uncommon to have a relative—particularly those nee...