![]()

PART I

RIVERS CONTROLLED

Cities and Their Watersheds

![]()

CHAPTER 1

RIVERS, INDUSTRIAL CITIES, AND HINTERLAND PRODUCTION IN QUEBEC IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES

Stéphane Castonguay

Rivers have long contributed to the articulation of urban spaces beyond the boundaries initially marked out by the fortification of the city. They have acted as navigation routes linking the urban milieu to its hinterland, particularly urban industries to sites for the extraction of raw materials and to markets for the distribution of products manufactured by the city’s artisans and workers.1 Just like the installation of water intakes for an aqueduct or the building of sewers within the city, the channelization of the river over long distances for navigation or the diversion of potable water for urban consumption integrated the river into sociotechnical systems in which rural populations confronted urban issues. The same was true of energy facilities that were moved out of the city. Water-based as they were, hydraulic mills had fostered the installation of factories along the edge of urban rivers, where the resources and products of industry were also conveyed by water transport. However, the invention of hydroelectric power generation at the end of the nineteenth century and, more importantly, of technologies to distribute electricity over long distances ended the dependence of the city’s industrial elements on a nearby river and opened up the urban space.

Thus, the river was constitutive of the hinterland-building process, not only through the integration of distant territories and their incorporation into networks but also through the supply of elements (energy, potable water, natural resources, and industrial materials) necessary to the industrialization and urbanization processes. Furthermore, by changing the river’s hydrology or compromising its quality, peri-urban facilities built to support industrial activity extended not only the territory of the city but also its environment and its political ecology. Flood risks and access to water of sufficient quantity and quality were at the heart of conflicts that arose from ecological changes, and revealed the power relations among the many users located along the river.2 They also indicated that the transformations in riverine environment that accompanied the processes of urbanization and industrialization were part of the territorial dynamic that shaped urban space. And while the latter ended up loosely corresponding to the contours of the watershed, it nevertheless exhibited a variable geometry, partly caused by ecological phenomena and partly resulting from sociohistorical factors.3

Yet studies on the spatial dynamics underlying the extension of the metropolis have only recently included in their analyses of land-occupation schemes the riverine elements and environmental changes arising from the influence of urban and industrial milieus on their emerging hinterlands.4 While environmental historians have recast the study of city-country relations by focusing their analysis on the environmental transformations that accompany the establishment of metropolises, the exchange networks underlying these relations remain essentially understood in their land forms—roads, railways, highways.5 The fundamental form of communication and integration that is the river needs to be further examined, along with the spaces commanded by its usage and representations, as well as its materialities.

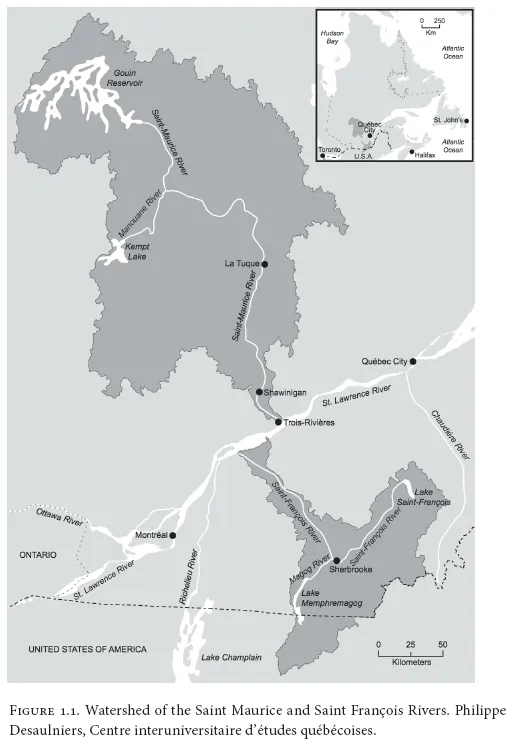

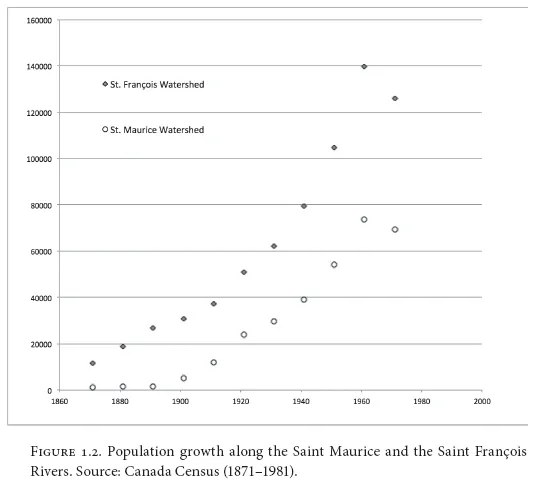

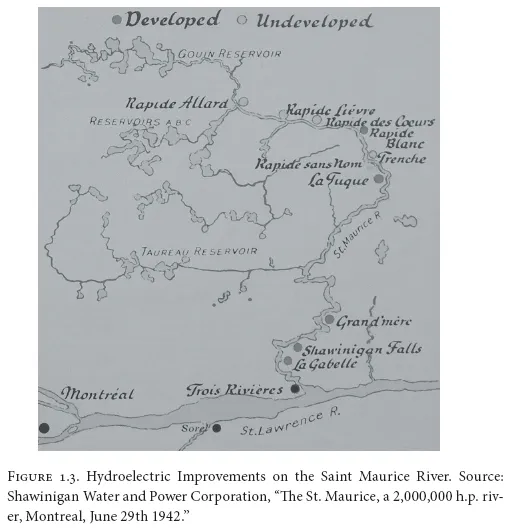

By contrasting the extension of the urban space of two cities located in different watersheds, this chapter seeks to understand riverine transformations in relation to urbanization and industrialization processes and to identify the role of the hydrology, ecology, and socioeconomy in hinterland formation. Sherbrooke and Trois-Rivières, the two cities under discussion, are located on tributaries running south and north of the Saint Lawrence River: the Saint François and the Saint Maurice Rivers (fig. 1.1). These rivers share many commonalities, both hydrological and historical. They both exhibit an important declivity, and a series of dams punctuate their hydrological regimes (figs. 1.2 and 1.3). Both rivers underwent a series of ecological and structural changes as of the middle of the nineteenth century following the establishment of sawmills and riverine infrastructures for wood floating. In the first decades of the twentieth century, a governmental agency proceeded to transform their respective headwaters into large reservoirs to ensure a regular flow; the construction of dams for energy production and flow regulation, along with other features of the second industrial revolution, further transformed their fluvial landscapes. Dams, mills, and factories were built at the confluence of their many tributaries, and urban centers evolved from these industrial nodes. These human transformations of the riverine environment accentuated the natural phenomena that annual precipitations provoked, such as erosion and floods, and that modified the beds and banks of both rivers. However, the two rivers also differ in length, degree of declivity, and pace of flow. Their watersheds also present specific features that affected the rate and density of their settlement, the Saint Maurice River being located in a rocky, sandy valley of poor fertility, while the watershed of the Saint François River offers a more varied topography, partly fit for agriculture and more suited to colonization. Because their riverine environments presented different possibilities for settlement, the watersheds of the Saint François and Saint Maurice Rivers were subjected to diverging patterns of urbanization and industrialization, with a consequent demographic growth and land-occupation scheme that influenced cultural representations of the river. Therefore, while similar driving forces transformed the Saint Maurice and Saint François Rivers into urban, industrial rivers, distinct natural and social factors influenced the rhythm of hinterland formation throughout the two watersheds.

SETTLEMENT, URBANIZATION, AND THE EARLY INDUSTRIALIZATION OF RIVERS

Urbanization of the riverine landscape followed different patterns along the Saint Maurice and Saint François Rivers. Topographical features on the north and south shores of the Saint Lawrence River influenced the rate and type of settlement, and the hydrology partly encouraged the selection of specific locations for the growth of urban centers. However, the intensity of colonization activities and the extent of settlement on the riverbanks determined the vulnerability of riverine populations to inundations, and the establishment of communication routes along the shores and their consequences on land use patterns. Most of all, these variables framed how, on the north and south shores of the Saint Lawrence River, the Saint Maurice and Saint François Rivers were transformed and experienced different patterns of industrialization. To capture these transformations, I refer to a process described by historian Eva Jakobsson, who coined the phrase “industrialization of rivers.”6 While Jakobsson strictly referred to fluvial transformations executed to inscribe a river into a sociotechnical system for the production of hydroelectric power, my use of the phrase differs slightly since my analysis emphasizes the formation of an economic system based on the integration of different industrial systems—for the production of hydropower, pulp and paper, and aluminum, as well as log driving and touristic and recreational activities.

Located between Montreal and Quebec City on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence River, the city of Trois-Rivières benefited from the resources of the Upper Mauricie area, where the abundance of furs directed its commercial growth since the seventeenth century.7 The Saint Maurice River acted as a route toward these resources. Yet except for a few parishes established on the lowlands of the Saint Lawrence River and Trois-Rivières—which had become the head of a judicial district and a diocesian siege—the opening of the hinterland gave way to little settlement beyond the immediate banks of the river. By the late eighteenth century, the pioneer front of colonization in New France had stopped at the edge of the Precambrian Shield.

Forest exploitation made continental penetration possible when, following the continental blockade during the Napoleonic Wars, Canada and its provinces started supplying white pine to the British Empire, and then, some decades later, to the construction industry in the United States after the American Civil War. Connected to international markets and served by an important harbor located at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence River, Trois-Rivières benefited from the growth of the forest industry throughout the Saint Maurice valley. Crown lands were quickly transferred to entrepreneurs who oversaw the clear-cutting of vast forest areas until the mid-1870s, when pine trees became scarce and an economic crisis caused world trade to slump.

To be exported, lumber needed to be driven down the watershed, but given the inexistence of adequate means of transportation before the advent of the railway in the Upper Mauricie area, the Saint Maurice River proved to be the fastest, least expensive way of driving wood to the confluence of the Saint Lawrence River. Yet the route from the Upper Mauricie to the harbor of Trois-Rivières was a difficult one, and navigability was interrupted in several locations, partly because of rapids but mostly because of steep reaches where rafts were repeatedly destroyed and forest entrepreneurs lost logs and profits.8 The construction of slides at these locations required financial and technical assistance from the provincial government. Starting in the middle of the nineteenth century, heavy public investment by the colonial government of the province of Canada enabled the transformation of the river and its insertion within a technical system for timber exportation. In its annual report for 1852, the very same year that the first paper mill was installed on the Saint François River, the Commissioner of Crown Lands insisted on the need to transform the river for the transportation of logs,9 and thereafter a series of installations enabled the timber of the Upper Mauricie to reach the Saint Lawrence River and the harbor and sawmills of Trois-Rivières. At Shawinigan, where falls and rapids prevented the floating of log cribs any farther down the river, the government proceeded to construct a 335-meter log slide and 4,500 meters of retaining booms, one above the falls and the other below in the lower bay, with pillars to retain the booms despite the current.10 While it heavily subsidized wood-floating infrastructure, the government proved to be less generous toward the funding of road improvement and railway construction. Investment in these domains might have facilitated the colonization of the Saint Maurice valley, but on the other hand colonization and forest exploitation seemed to compete for public money and for public land.11 Forest camps moved according to the availability of white pine, and the transformation of the forest cover from fire and intensive exploitation deterred settlers from establishing villages. Instead, they followed the forestry entrepreneurs in search of new logging sites. Settlers not only earned their living by supplying farm products to forest camps, they also sold the logs from their land-clearing activities. Once the soil fertility was depleted and the lumber camp had moved on, the settlers relocated.

While the preindustrial history of the Saint François River was also stimulated by the lumber economy, land occupation in the Eastern Townships followed a different dynamic. Agricultural colonization drove initial settlement of the area, where prosperous agriculture enabled the growth of villages and towns thanks to the establishment of dams and mills. Partly orchestrated by the British American Land Company (BALC), settlement initially involved Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution who squatted or acquired small plots of land to colonize a large area south of the Saint Lawrence valley just north of the American border.12 There, soils of varying fertility and forest resources offered some prospects for the establishment of a pioneering community.

Numerous sites along the Saint François River offered the possibility of harnessing hydraulic energy, and these gave rise to several towns and villages in the Eastern Townships. One of these was Sherbrooke, where the steep gorges surrounding the Magog River turned out to be well suited to hydropower.13 In 1834, the BALC erected a dam upstream from the falls, at the head of Petit Lac Magog, which was transformed into a water reservoir.14 The dam supplied hydraulic energy by mechanical transmission to a sawmill built by the BALC in 1837. Thereafter, four additional dams were erected on the Magog River, and the BALC rented riverine land to manufacturers that set up woolen mills, smelters, and tanning yards. The city of Sherbrooke evolved from these installations.

Because of its declivity and difficult passages that necessitated long portages, the Saint François River was of limited navigability. Nevertheless, it provided the pathway for the construction of a railway link between Montreal and the American seaport of Portland, Maine. The advent of the railway accelerated the peopling of the Eastern Townships, not only along the Saint François River but also across the territory, as the railway tracks crossed the Eastern Townships; smaller villages emerged and accommodated services and small industries. Thereafter, the exchange network linking the Eastern Townships to its suppliers and markets encompassed a more diversified range of products and resources, as factories in towns like Sherbrooke relied on the importation of staples such as cotton from the southern United States, iron from Nova Scotia, wool from Australia, and rubber from South East Asia.

The advent of the railway in 1853 further stimulated the urbanization of the Saint François River that influenced the siting of the villages.15 New towns sprang up, such as Windsor Mills and East Angus, built at the confluence of the Saint François River and the Watopeka and the Eaton Rivers, respectively. Other sites on the Saint François River benefited directly from sufficient gradients for dams to be built, enabling the growth of small industries that attracted people and resources. At Brompton Falls, a few kilometers downstream from Sherbrooke, C. S. Clark and Company built Canada’s largest sawmill to benefit from the railway’s proximity to the river.16 The company acquired the cutting rights of the Upper Saint François area, where during the winter it sent its workers to cut down trees to be carried down the river in springtime. Along with other sawmill owners, it installed slides for floating and driving logs downriver.17 These installations increased the intensity of flooding events and the resulting damage, if only because ice jams proved more frequent. Furthermore, the destruction of log cribs caused damage—farmers complained about the logs littering their agricultural fields and the destruction of their farm buildings by flooding caused by poor maintenance and management of dams and sluices.18 By transforming the river and the forests, industrialists operating at the confluence of the Saint François River and its tributaries therefore provoked changes throughout the watershed that affected riverine populations removed from the urban centers.

Specific relationships with the river resulted from patterns of land settlement and riverine transformations. In the Saint Maurice valley, as financial resources were devoted to improving the riverine infrastructure to facilitate log driving, the lack of incentives to settl...