![]()

1

Breaking Up and Building, 1890–95

Shahbash! The smell of your good deeds in our city has reached to Kabul and nearly to London.

Boatmen after the Srinagar fire of 18921

The first thing one noticed was his bent nose; and the laughing blue eyes. The blue eyes he got from his mother and the bent nose from boxing but the laughter was all his own. He was short and slight and, at 27, full of confidence and zest for all the experiences of his new life as a member of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) of London ‘going out to the field’. On the voyage to India he offered the Captain his services as chaplain but was not averse to pranks; Clara Warren,2 another young missionary, thought him a nice little man but hoped he would not frighten her again by climbing the mast beyond where the leaders are and there losing his new imperial hat, the solar topi. For this he was punished by being tied to a spar.

For the past two years Cecil Biscoe had been working as a curate in the slum districts of London, developing unorthodox methods to help the most disadvantaged people in English society, before being accepted as a missionary to go to Kashmir. He knew so little about it that he had to visit the Royal Geographic Society library to find out where it was, but he was confident that he would manage.

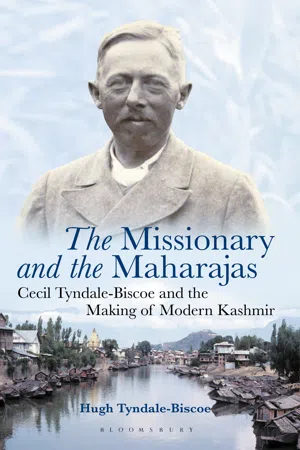

Figure 1 Cecil Tyndale-Biscoe aged 38 years

India was utterly different from England – the diversity of people, the strange noises, and the dust3 – yet he felt at ease as he was passed from one English person to another. In Lahore he met a young subaltern who asked him why a fellow like him from a public school and Cambridge would want to waste his life as a missionary. In Amritsar he attended the induction of the new Colonel of the 3rd and 4th Gurkha Regiments, where he met an old boy of his public school, before meeting the missionaries at the home of Robert and Elizabeth Clark. The Clarks had been in India for 40 years and were the Head of the Mission in the Punjab and Kashmir. They were a formidable pair: he had been a mathematical wrangler at Cambridge and she could speak several European languages and read Sanskrit before she even went to India. Mrs Clark kept the younger missionaries under strict control; the men dared not speak to the women or offer them coffee. However, after the prayer meeting Biscoe ignored the protocol, surprising Mrs Clark by his forwardness.

Biscoe had three advantages in the new society he was entering: having been born into the English upper class, he moved easily among the senior civilians and military men; he subscribed to the prevailing beliefs in the superiority of British ways and the importance of their rule in India – the White Man’s Burden; and his rowing prowess at Cambridge and Henley only six years before had given him a new confidence and brought him that special respect that elite sportsmen receive from other men.

In the missionary circle he was entering, however, these attributes were not appreciated. He was too independent for the senior missionaries and insufficiently pious for the others; when asked by one of them if he was among the 40,000 ‘saved souls’ he said he very much hoped not as he didn’t want to keep anyone else out. This tension would dog him in all he tried to do in Kashmir. While his work was admired by the British civilian and military men, it was never well supported by the CMS for whom he worked.

Medieval Kashmir

Biscoe left Amritsar for Rawalpindi at the beginning of December 1890 by ekka, a horse drawn country cart and a very bumpy ride; then the final journey into Kashmir in a slightly more comfortable tonga with sprung wheels, on the new cart road that had been completed earlier that year, winding its way along the cliffs above the thundering roar of the Jhelum River. After three days in the tonga driven by Jehu the Pathan, negotiating land slips and changing ponies, they reached the wide valley itself at Baramula. Wheeled traffic went no further; indeed, wheels were still unknown in Kashmir.4 For everyone the 32 miles to the capital, Srinagar, was either by boat or pony.

Arriving at Baramula at midnight they were surrounded by crowds of men with flaring torches of resinous pine, eager for Biscoe’s custom. His luggage was seized and he, thinking he had been robbed, lashed out with Jehu joining in. One man in a dirty nightgown was holding out a letter for him but Jehu knocked him to the ground. The letter was from a fellow missionary, Arthur Neve, saying that he had sent this man with a boat to bring him to Srinagar – if Jehu had a different plan it was now thwarted, the messenger placated and the luggage and young sahib taken to Iqbal’s waiting doonga. This was a long flat-bottomed craft made of sweet-scented deodar,5 with a low, thatched roof and sides of bull-rush matting; a room at the front was furnished with floor rugs for the passenger and a room at the back for the crew of three. The latter included a mud-plastered fireplace for cooking, the smoke from which, mingled with the pungent scent of tobacco from the boatmen’s hookah, pervaded the whole boat. For many young Englishmen coming on leave to Kashmir, the doonga owner would provide young Kashmiri women to ease the tedium of the three day trip to Srinagar; Biscoe was not offered this service but two years later his brother was; and was properly outraged. But for those who accepted, the price of the trip rose from 4 rupees to as much as 500, particularly if the sahib was sufficiently senior and anxious for discretion.

They set off in the morning, two men towing from the bank and the wife steering in the stern. At Sopor, where the river widens into the Wular Lake, they stopped; the crew would not cross in the afternoon because sudden squalls, known as the Nag Kawn, can blow up easily swamping a doonga. As Biscoe was trying to continue, the headmaster of the local school, Pandit Amar Chand, who could speak English appeared6 and explained the danger to him but then helped him persuade the crew to continue. This was his first encounter with an educated Kashmiri and one who would later join his staff and be a great help to him. For now they parted and he with Iqbal continued in the doonga across the lake, putting up thousands of wild duck and geese in the process, and safely tied up before dark.

On a later trip across the lake his doonga was actually caught in the Nag Kawn.7 The matting sides flapped; the water lapped against the sides as the wind whipped up the waves; the boatman shouted to his wife and she shouted back words that Biscoe could not understand; the waves splashed more violently and began slopping in over the sides. Then the boatman put down his paddle and rushed towards his wife and infant and, taking off his turban, started to tie them all together. When Biscoe asked him what he was doing, he said that this way they would all drown together. ‘Please, can’t you spare part of your turban for me as well?’ The boatman was so taken aback that he burst out laughing at the idea of a ‘lord sahib’ begging from him and lost his fear. He took up his paddle in the bow and Biscoe took another in the stern and they got the boat facing up into the wind instead of broadside on.

Figure 2 Sketch of the Mission School at the Third Bridge, drawn by Biscoe in 1892 for first log

But back to his first journey, the next day it was snowing and bitterly cold as the doonga was slowly towed up the now placid Jhelum River. Debris of the city floated by, dirty foam, floating straw and bloated carcases on which vultures perched, and their rancid smell and the smoke from the kitchen drove him out to run along the bank with the men. On the third day they smelt the city before they reached it: spices and cooking onions, riverside latrines and more rotting carcases. Passing under Safah Kadal, the seventh bridge, the sounds of the city joined their senses. Under the bridge of great deodar timbers hundreds of starlings flew about, creening kites8 wheeled overhead or swooped down to snatch a morsel from the river, bells rang out from Hindu temples, vendors called their produce, boatwomen quarrelled loudly from their moored kutchus – the great barges of commerce on the river – and pi-dogs yelped as they were driven off. They passed under Nawa Kadal, Ali Kadal and Zana Kadal, the sixth, fifth and fourth bridges and, as an accomplished waterman himself, Biscoe admired the boatmen’s skill in navigating the doonga between the piles and against the current, taking advantage of every swirl and eddy, using every crack and hole to pole the boat forward. Now on the right bank they passed the great Shah-i-Hamdan Mosque that commemorates Mir Sayeed Ali Hamdani, who in 1380 brought Islam to Kashmir from Persia; the mosque was originally built in 1392 over a Hindu temple to the goddess Kali, it was twice destroyed by fire and last rebuilt of deodar in 1732. On the opposite bank they passed the Pathar Masjid Mosque built by the Mughal Queen Nur Jehan in 1620; not used as a mosque, because it was raised by a woman, but very useful as a granary.

Lining both banks of the river and rising from plinths of ancient carved stone were three and four storey timber houses with intricate lattice windows and roofs of earth on birch bark; these were interspersed with broad stone steps leading down to the water’s edge. Here people were washing, collecting water in large earthen pots, gossiping or stepping into shikaras, the water taxis of the city. Just above Fateh Kadal, the third or Gallows Bridge, they passed some tall buildings on the left bank one of which, though Biscoe didn’t then know it, would be at the centre of his life for 50 years. Some of the boys, curious to glimpse their new teacher were astonished to see a fair-haired youth standing on the prow of the doonga.

Near it on the same bank was the Rago Nath Temple with its high dome of silvery shining metal. Headquarters of the Hindu Dharam Sabha or High Council where important religious matters were decided, it would also figure largely in Biscoe’s life. The stretch of river between Habba Kadal, the Bridge of Air, or gossip and rumour, and the King’s Bridge, Amira Kadal, was the preserve of Maharaja Pratap Singh: the left bank was almost wholly occupied by his palace and the Zenana or women’s palace, and by the opposite bank were moored the royal barges with seats for 60 paddlers, the smaller 30-paddle parindas, or birds, and the fine steam launch given to his father, the late Maharaja Ranbir Singh by Queen Victoria in 1875.9 A century on it now rests in the Museum garden across the river.

Upstream of the palace the river makes a sharp bend and here the city opened out with large gardens on the left bank and the British resident’s garden on the right bank. Upstream of this on the same bank was the Munshi Bagh, a large park shaded by giant chenar or plane trees, which the previous Maharaja set aside as one of the two places where British people could stay. There were bungalows for the missionaries and the few foreigners employed by the State, known as the Barracks, and sites where summer visitors could set up their tents.

Here Biscoe’s journey ended as he was greeted by his fellow missionaries, Hinton Knowles the padre, and the doctors Arthur and Ernest Neve, with whom he would stay because Mrs Knowles was ill with typhoid. The Knowles had been in Kashmir for seven years preaching the Gospel in the villages and, against strong opposition from the State, running a Mission School for Hindu boys in the city. Knowles was a scholarly man; he was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of London, had recently written a book on Kashmiri folktales10 and was currently translating the Bible into Kashmiri. He was 36 and had been pleading with the Society to relieve him of the school so that he could concentrate on other activities. The Neve brothers were 31 and 29 respectively but unlike Biscoe, were tall, solemn men with military moustaches. Both had graduated with high honours from Edinburgh Medical School and come out to Kashmir within a year of graduation. Arthur had been in Kashmir for eight years and his brother for four. Neither was married and would not be so for many years; both were deeply engaged with running the Mission Hospital and were already fluent in Kashmiri and Urdu. Their recreation was exploration of the mountainous country to the north and east of Kashmir. Arthur had already made two quite extensive expeditions to Baltistan in the north and was at the time trying to persuade the Society to let him make a trip to Kafiristan that lies between Afghanistan and Chitral to the west of Kashmir.11 Ostensibly his purpose was to bring the Gospel to the non-Muslim animists, known as Kafirs, but there was a large element of adventure in his proposal and he was frustrated by the lack of support he was getting from Lahore. In the view of the British Resident in Kashmir, ‘Neve is a clever fellow but extremely conceited and greedy of power and influence’.12 Ernest had not yet made any expeditions on his own but in a few years would visit Leh with Biscoe and be the first to climb many of the surrounding peaks, including the 17,000 feet Mount Kolahoi, and much later was a foundation member of the Himalayan Club.

Ernest believed that:

Medical mission work is completely in accordance with the spirit of the East. The medical missionary, as healer and evangelist, goes forth on a very distinct mission, and one with the highest Scriptural and humanitarian sanctions. His ideals are the highest. His failures are due to inherent weakness or unfavourable environment and not to low aim. His life is a peculiarly happy one, spent as it is in daily ministering to the needs of those who are in pain and sorrow, and pointing at the same time, as he does, to the Source of all comfort.13

On that first winter afternoon of Biscoe’s arrival in Srinagar, the Neve brothers took Biscoe for a pony ride up the nearby Shankra Charya hill to show him the view of the Dal Lake to the north, lying below Mount Mahadeo on the right and the Hari Parbat Fort to the left. Far away in the south and west, the snow-covered peaks of the Pir Panjal Range formed a backdrop to the broad windings of the Jhelum River with the medieval city spread along both ban...