- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

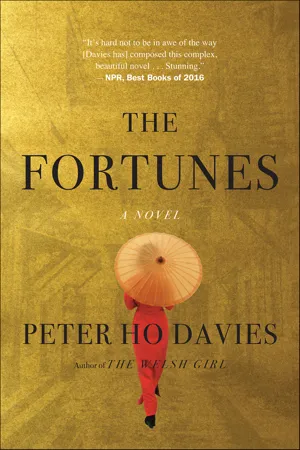

An NPR Best Book of the Year: "The most honest, unflinching, cathartically biting novel I've read about the Chinese American experience." —Celeste Ng, #1

New York Times–bestselling author of

Our Missing Hearts

Winner, Anisfield-Wolf Book Award * Winner, Chautauqua Prize *Finalist, Dayton Literary Peace Prize * A New York Times Notable Book * A Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year

Sly, funny, intelligent, and artfully structured, The Fortunes recasts American history through the lives of Chinese Americans and reimagines the multigenerational novel through the fractures of immigrant family experience.

Inhabiting four lives—a railroad baron's valet who unwittingly ignites an explosion in Chinese labor; Hollywood's first Chinese movie star; a hate-crime victim whose death mobilizes the Asian American community; and a biracial writer visiting China for an adoption—this novel captures and capsizes over a century of our history, showing that even as family bonds are denied and broken, a community can survive—as much through love as blood.

"Intense and dreamlike . . . filled with quiet resonances across time." — The New Yorker

"Riveting and luminous . . . Like the best books, this one haunts the reader well after the end." —Jesmyn Ward, National Book Award-winning author of Sing, Unburied, Sing

"A moving, often funny, and deeply provocative novel about the lives of four very different Chinese Americans as they encounter the myriad opportunities and clear limits of American life . . . gorgeously told." —Chang-rae Lee, Buzzfeed

"A poignant, cascading four-part novel . . . Outstanding." —David Mitchell, The Guardian

Winner, Anisfield-Wolf Book Award * Winner, Chautauqua Prize *Finalist, Dayton Literary Peace Prize * A New York Times Notable Book * A Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year

Sly, funny, intelligent, and artfully structured, The Fortunes recasts American history through the lives of Chinese Americans and reimagines the multigenerational novel through the fractures of immigrant family experience.

Inhabiting four lives—a railroad baron's valet who unwittingly ignites an explosion in Chinese labor; Hollywood's first Chinese movie star; a hate-crime victim whose death mobilizes the Asian American community; and a biracial writer visiting China for an adoption—this novel captures and capsizes over a century of our history, showing that even as family bonds are denied and broken, a community can survive—as much through love as blood.

"Intense and dreamlike . . . filled with quiet resonances across time." — The New Yorker

"Riveting and luminous . . . Like the best books, this one haunts the reader well after the end." —Jesmyn Ward, National Book Award-winning author of Sing, Unburied, Sing

"A moving, often funny, and deeply provocative novel about the lives of four very different Chinese Americans as they encounter the myriad opportunities and clear limits of American life . . . gorgeously told." —Chang-rae Lee, Buzzfeed

"A poignant, cascading four-part novel . . . Outstanding." —David Mitchell, The Guardian

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9780544263789Subtopic

Literature GeneralCelestial Railroad

Beset by labor shortages, Crocker chanced one morn to remark his houseboy, a slight but perdurable youth named Ah Ling. And it came to him that herein lay his answer.

—American Titan, K. Clifford Stanton

1.

It was like riding in a treasure chest, Ling thought. Or one of the mistress’s velvet jewel cases. The glinting brasswork, the twinkling, tinkling chandelier dangling like a teardrop from the inlaid walnut ceiling, the etched glass and flocked wallpaper and pendulous silk. And the jewel at the center of the box—Charles Crocker, Esquire, Mister Charley, biggest of the Big Four barons of the Central Pacific Railroad, resting on the plump brocaded upholstery, massive as a Buddha, snoring in time to the panting, puffing engine hauling them uphill.

It was more than two years since the end of the war and the shooting of the president—the skinny one, with the whiskery, wizened face of a wise ape—who had first decreed the overland railroad. His body had been carried home in a palace car much like this, Ling had heard Crocker boast. Ling pictured one long thin box laid inside another, the dead man’s tall black hat perched atop it like a funnel. People had lined the tracks, bareheaded even in the rain, it was said, torches held aloft in the night. Like joss sticks, he reflected.

For a moment he fancied Crocker dead, the carriage swagged in black, and himself keeping vigil beside the body, but it was impossible with the snores alternately sighing and stuttering from the prone form. “Locomotion is a soporific to me,” Crocker had confessed dryly as they boarded, and sure enough, his eyes had grown heavy before they reached Roseville. By the time the track began to rise at Auburn, the low white haze of the flats giving way to a receding blue, vegetal humidity to mineral chill, his huge head had begun to roll and bob, and he’d presently stretched himself out, as if to stop it crashing to the floor. Yet even asleep Crocker seemed inexorable, his chest surging and settling profoundly as an ocean swell, the watch chain draped across it so weighty it must have an anchor at one end. Carried to the Sierra summit, he looked set to rumble down the lee side into Nevada and Utah, bowling across the plains, sweeping all before him.

Ling knew he should be looking out the window, taking the chance to see the country, to see if the mountains really were gold, but he hadn’t been able to take his eyes off the steep slope of his master’s girth. My gold mountain, he thought, entertaining a fleeting vision of himself—tiny—scaling Crocker’s imposing bulk, pickaxe in hand, following the glittering vein of his watch chain toward the snug cave of his vest pocket.

Ling didn’t own a watch himself, of course, but shortly after he entered service Crocker had had him outfitted with a new suit from his dry goods store, picking it out himself. The storekeep had been peddling a more modest rig—“a fustian bargain, as it were!”—that the big man dismissed out of hand as shoddy. He settled on a brown plaid walking suit instead, waving aside the aproned clerk to yank the coat sharp over Ling’s narrow shoulders. “There now!” Crocker declared, beaming at him in the glass. “Every inch a gentleman’s valet.” He taught Ling how to fasten only the top button of the jacket, leaving the rest undone, to “show the vest to advantage,” and advised him he needn’t bother with a necktie so long as he buttoned his shirt collar. “Clothes make the man,” the circling clerk opined, sucking his teeth. “Even a Chinaman.” And then, of course, there must be a hat, a tall derby, which Ling balanced like a crown, eyes upturned. As a finishing touch Crocker had tucked a gold coin, a half eagle, into Ling’s vest pocket—a gift, though the cost of the outfit itself would come out of his wages—where Ling could swear the thing actually seemed to tick against his ribs like a heartbeat: rich, rich, rich.

He patted it now, as he finally turned to take in the scenery—the pale halo of sere grass along a ridge, the stiff flame of a cypress, the veiled peaks beyond—wondering despite himself if the mountains might glister through the flickering pines.

2.

Gold Mountain. Gum Shan. Ling had never even laid eyes on gold before he left Fragrant Harbor. It had made him feel furtively foolish. There he was, sent to find it and he’d never seen it in his life. What if he didn’t recognize it? How yellow was it? How heavy? What if he walked right by it? “How can you miss it, lah!” Aunty Bao had snapped, over the snick of her abacus. “There’ll be a mountain of it, stupid egg!” But Ling wasn’t so sure. They came from Pearl River. If it were really full of pearls, he wanted to tell her, he wouldn’t be sailing to Gold Mountain.

“Besides,” Big Uncle insisted, “you have seen gold before.” They were in his cabin on the “flower boat,” the moored junk that housed the brothel Big Uncle owned and Aunty Bao—palely plump as the pork buns she was named after—managed for him. Yes, Big Uncle was saying, a grandfather had made his fortune prospecting in Nanyang. The old man had had a mouthful of gold teeth. As an infant, Ling had even been given gold tea, a concoction made by pouring boiling water over a piece of gold, supposed to ensure luck. Didn’t he remember? Ling tried. For a second a vast, bared smile, glistening wetly, rose up before him and with it a feeling of fear, an impression, as the lips drew back, that beneath the flesh the man himself was made all of gold, that behind the gold teeth lay a gold tongue clanging in a gold throat. But the only “grandfather” he could actually recall was a broken-down old head swabbing the decks who had already lost those teeth, pulled, one by one, to pay for his opium habit. All that was left was a fleshy hole, the old man’s lips hanging loose as an ox’s, his tongue constantly licking his bruised-looking gums.

Still, Big Uncle pressed, “Gold is in your blood, boy!”

Perhaps, Ling thought, but he’d learned to doubt his blood.

His people were of that reviled tribe of sea gypsies known as Tanka, “egg folk,” after the rounded rattan shelters of their sampans. Forbidden by imperial edict to live on land and only grudgingly tolerated in ports and coastal villages, for generations they’d made a thin living as fishermen, mocked for their stink by the Han Chinese. Latterly they’d made an even more odious, if also more lucrative, reputation smuggling opium for the British and pimping out their women to them for good measure. Ling’s mother had been one of these haam-sui-mui, or “saltwater girls.” “A lucky one,” Aunty Bao observed with a moue of envy, a beauty plucked from the brothel by a wealthy foreigner and established in her own household. Only his mother’s luck had run out fast. She’d died in childbirth, and her protector, Ling’s father, had settled a generous sum on Big Uncle to take the infant off his hands. All Ling had left of her was her name. He had grown up on board the flower boat along with the other bastards, a clutch of them grudgingly provided for until they could be disposed of profitably, the girls as whores, the boys as coolies (a C or P daubed on their chests in pitch for Cuba or Peru, where they’d labor in the sugar plantations or mine guano).

The only children Big Uncle kept were his lawful sons by Aunty Bao. Their father styled himself a respectable Chinese comprador—frogged brocade jacket over ankle-length changshan, silk cap smoothed tight over shaven head—grooming his boys to run the family business, even if that business consisted of a brothel, an opium den, a smuggling fleet. Big Uncle’s sons were plump and well dressed—on land they could pass for Cantonese—but more than anything Ling envied them their father’s name. As a small child he would watch them following the big man, listening as he taught them his trade (“Opium and sex belong together; the one enhances the other.” “Or at least prolongs it,” Aunty Bao pouted) and Ling began to trail them in turn, imitating their deference, their attentiveness, until the oldest boy, thinking he mocked them, shoved him to the deck with a thud. Big Uncle had turned at the sound and casually, as if stretching, struck the bully about the head. Ling recalled glimpsing the heavy leather wrist guards of a hatchet man beneath his silk sleeves. “They’re worthless if they’re crippled,” Big Uncle noted calmly over Elder Brother’s sobs, patting Ling’s shoulders and examining him. “How are you?” he asked, and Ling, eyes wide but dry, piped up, “Well . . . father!” And the man smiled on him from beneath his sleek mustache.

Young Ling had no hope, even as he searched the faces of the white ghosts who frequented the brothel, of finding his own father. The man had given him up, after all. But he still wanted a father, needed one. To be fatherless in China, he understood, was to be poorer than the hungriest peasant.

He had made himself useful about the boat, running errands for the girls, waiting on their customers. His specialty was preparing opium for the men: pinching and rolling the doughy pills between his small fingers, holding them over the lamp on the needle until they began to smoke and bubble, then deftly depositing them in the bowl of the waiting pipe. Over time, squatting at their feet, he began to pick up shreds of their language—English mostly, but also phrases of Portuguese and French, Italian and Spanish—to go along with his Cantonese. It got to be a performance, men calling him “little parrot” and tipping him in coin (from which Aunty Bao took her customary cut). Once he saw Big Uncle watching him, and a few days later the man gave him a gift, a pet cricket folded up in a tiny cage made from a carved bamboo cylinder. He cherished it, peering in at it though the narrow bars, falling asleep to its ringing song, like a prayer or a promise. He wept when it fell silent, hiding for days, thinking he’d be beaten for letting it die (though Big Uncle never asked about it again).

Aunty Bao must have seen his hopes in his face. When he grew taller, she insisted he leave—“He’ll fall in love with one of the girls, lah! Bad for business!”—and so Big Uncle sent him on his way, though not to Peru or Cuba but to “Big City,” San Francisco. He already sold girls from his nursery to supply the brothels on Gold Mountain. The boy with his pocketful of English might do well there too, he reasoned.

“Off to your own kind,” Aunty Bao crowed, but Ling, despite his misgivings, went willingly enough, eager to prove himself a dutiful son. “Your passage is paid,” Big Uncle told him, “a position arranged.” Ling had bowed, promised to send money, and the old gangster nodded complacently. That was when he’d told him gold was in his blood. Ling was fourteen years old. He knew nothing of America, nothing of mining—pictured himself drawing gold from the dirt like the apothecary straining over that old grandfather, yanking the gold from its roots, brandishing a nugget in a pair of pliers, wet and a little bloody—but he vowed to strike it rich and return in triumph. (His ideas of gold were to be even more confused when, on the voyage out, the captain had lowered the dory to recover an odd floating rock, as it seemed, the color of pale tea. Ambergris! the crew exulted. Floating gold! Though later Ling was to learn it was whale puke.)

Outside the carriage window, the trees—sharp firs poking through their layered foliage like the spike impaling receipts on Crocker’s desk—fell away as the train ascended a ridge and the view opened before him. The distant peaks shone in the morning light, not gold, of course, but brilliant white, and as they climbed he watched the flakes tumbling past the window, mixed with sparks and smut from the smokestack.

Snow, and it was June.

The flurry whipped and twisted like a swarm, so blithely nimble, even as he felt the train grow taut, girding against gravity. And then an updraft swooped in and sent it spiraling back into the sky.

Beneath the thunderous thrill of it all—Ling was used to accompanying Crocker about town, but never before into the field—lay a thrum of unease. He contemplated the idle men waiting at the end of the line, the striking Chinese, and wondered why Mister Charley had brought him along.

3.

He’d been with Crocker for a little over two years by then, since 1865. His first job off the paddle steamer in Yee Fow—Second City, as the Chinese knew Sacramento—had been at a laundry on I Street, one of the shanties backing onto China Slough, hauling boiling kettles from the stove to the great half-barrel tubs where his boss, Uncle Ng, a wiry Cantonese, sat smoking and working the soaking linens between his red callused feet, every so often tapping the ash from his pipe—“soo-dah!” as he pronounced it—into the suds like so much seasoning.

Ng wore a wispy beard and a sleepy mien, heavy-lidded, his head seemingly propped on the long-stemmed pipe clamped between his teeth, but he had a dark mole the size of a pea above the bridge of his nose, a third eye that seemed to squint whenever he furrowed his brow. His queue he coiled around his head to keep out of the laundry water (at first glance, vision bleary from lye, Ling had been scandalized to think Ng had cut his hair, imperial law requiring the queue as a mark of fealty), but he let a single strand sprouting from his mole grow long and silky, believing after the Chinese tradition, if against all experience, that it brought him luck.

Ng was an inveterate gambler, tucking his coins into his ears for safekeeping and absenting himself each evening and part of most days to play the lottery or dominoes or “precious dice,” whatever he could find. He’d bet on which starling would rise off a roof first, back one cockroach over another in a race, so long as there was someone to wager against. He would return invariably with tales of perspicacious wins and unforeseeable reverses, but it seemed to Ling as if they mostly evened out, which might have been the extent of Ng’s luck.

Not surprisingly, he was an indulgent boss, often leaving Ling unsupervised as if he were a partner, not an employee. Even when he was present during the day he was often stretched out, snoring, on an ironing platform, catching up on sleep from the night before. Ling took him for a fool—easy to see why he’d never amounted to more than a laundryman—but the old man’s neglect was mostly benign. Early on, with a sly show of solemnity, he confided his “mystery”—a few crumbs of blue from an ink block added to the rinse water to make the “white whiter”—but otherwise he offered little direction beyond a couple of quick stabs with his pipe stem, once at the wall of tightly wrapped parcels stacked like bricks, then at the heap of plump, sagging bundles tied up in sheets, their knotted corners twitching in the breeze like ears. “These clean, those dirty. You . . .” The pipe stem swung from one to the other. But when he found Ling a few days after he started with his hands blistered from washing, he clucked over them, dressed the wounds himself. “Why. You. Think. I. Use. My. Feet?” he asked, punctuating each word with a tacky dab of salve.

The other member of their household was a surly young woman who told him to call her Little Sister, though she seemed two or three years his senior. “Or I could call you Little Brother,” she offered pertly, seeing his hesitation. He blushed at the slang for penis. “Pleased to meet you,” he said, and she smiled thinly. Her hair was parted in the middle, swooping down over her ears in two glossy black wings after the Tanka fashion, but when he asked, Haam-sui-mui? she grimaced.

“They call us ‘soiled doves’ here.” Not Tanka then, by her accent, which was the same as Ng’s, but at least her profession was familiar.

“Half the laundries are brothels,” Ng explained cheerily. “Good business! There’s a dozen fellows to every woman in the state.” Ling thought of the ship he’d arrived on, packed so tightly with men they shared their bunks—three tiers, eighteen inches between—in shifts. He’d heard one sailor joke, Add some oil and they’d be sardines. And yet his abiding memory of his passage was of loneliness, despite (or perhaps because of) the cramped quarters, shunned as he was by many of the other sojourners for being Tanka. In San Francisco, though, surrounded by ghosts, he’d felt the disembarking crowd of Chinese draw tight together, himself among them, Han and Tanka, Cantonese, Hakka and Hoklo all as one.

Little Sister slept past noon, but when she emerged on Ling’s first day, Ng set her to teaching him the “eight-pound living”—ironing—which she consented to, grumpily.

“You?” Ling asked, surprised.

“Who you think had your job first?” she snapped, winding her hair into a tight bun a...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraphs

- Author’s Note

- GOLD

- Celestial Railroad

- SILVER

- Your Name in Chinese

- JADE

- Tell It Slant

- PEARL

- Disorientation

- Acknowledgments

- Reading Group Guide

- A Conversation with Peter Ho Davies

- Sample Chapter from A LIE SOMEONE TOLD YOU ABOUT YOURSELF

- Buy the Book

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Fortunes by Peter Ho Davies in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.