eBook - ePub

The Prisoners Of Breendonk

Personal Histories from a World War II Concentration Camp

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Fort Breendonk was built in the early 1900s to protect Antwerp, Belgium, from possible German invasion. Damaged at the start of World War I, it fell into disrepair . . . until the Nazis took it over after their invasion of Belgium in 1940. Never designated an official concentration camp by the SS and instead labeled a "reception" camp where prisoners were held until they were either released or transported, Breendonk was no less brutal. About 3,600 prisoners were held there—just over half of them survived. As one prisoner put it, "I would prefer to spend nineteen months at Buchenwald than nineteen days at Breendonk."

With access to the camp and its archives and with rare photos and artwork, James M. Deem pieces together the story of the camp by telling the stories of its victims—Jews, communists, resistance fighters, and common criminals—for the first time in an English-language publication. Leon Nolis's haunting photography of the camp today accompanies the wide range of archival images.

The story of Breendonk is one you will never forget.

With access to the camp and its archives and with rare photos and artwork, James M. Deem pieces together the story of the camp by telling the stories of its victims—Jews, communists, resistance fighters, and common criminals—for the first time in an English-language publication. Leon Nolis's haunting photography of the camp today accompanies the wide range of archival images.

The story of Breendonk is one you will never forget.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9780544556447Subtopic

German History 4.

The First Prisoners of Room 1

A typical barrack room at Breendonk.

In the weeks before Israel Neumann arrived at Breendonk, only about twenty other prisoners had been sent there. By the end of December, some sixty-five prisoners had been registered. The exact number of prisoners and their dates of arrival and release are not all known, however, since some of the records were lost or destroyed near the end of the German occupation. This was a slow start for a camp that would, for a short time, eventually house as many as 660 prisoners.

During the first ten months, about two-thirds of the prisoners at Breendonk were Jews, almost all of whom had emigrated from other European countries to Belgium. Most were arrested simply because they were Jewish or because they were common criminals already incarcerated when the Germans invaded.

All the early prisoners were initially placed together in Room 1, but as more arrived Schmitt and Prauss made a change. Since every prisoner was classified as either Jew or Aryan, Schmitt decided to split up the two groups and place them in separate barracks that first December. Jewish prisoners remained in Room 1; non-Jews were transferred to Room 6.

Even prisoner numbers reflected the classification system. Before the two groups of prisoners were divided, all incoming prisoners seem to have been given sequential numbers starting with 1. After the prisoners were separated, the numbering system was reconfigured: with few exceptions, Jews were given numbers from 1 to 160, while non-Jews were reallocated numbers over 160. Their original numbers were then reassigned to incoming Jews.

If there was any doubt whether a prisoner was Jewish, Schmitt or Prauss would ask the prisoner on arrival. It didn’t matter if the prisoner had been baptized in or had converted to another faith; if he had Jewish parents or grandparents, he was assigned to Room 1.

By the end of December 1940, Room 1 was filling up.

Israel Steinberg, prisoner number 26, was most likely taken to Breendonk the same day as Israel Neumann. Born in Poland and a tailor by trade, he was a petty thief who had been arrested and convicted for pickpocketing in Austria in 1930, with subsequent arrests for the same crime in Germany and Belgium. After he was expelled from Belgium in 1937, he returned home to Poland, where he claimed to have a wife and five children. In 1938, he tried to make his way to Palestine. On the way, he was arrested in Vienna, expelled from Italy, and ended up in Belgium once again, where he was arrested in July 1939. Police officers had observed him watching people withdraw cash from the bank in a Brussels post office, as if he were planning to rob them. When he was taken into custody, the police found that he did not have a passport, only a Polish identity card. Although he claimed to have arrived in the country seven days earlier, he could not provide officers with an address. Escorted to within a few miles of the border, he was told to cross into Germany and not return. Instead, he traveled to another Belgium town, where he was again caught in the act of robbery. This time, he was sentenced to ten months in jail and placed in the Saint-Gilles Prison in Brussels. After the Nazis took control, they transferred him to Breendonk, where he was told to take care of the pigs, a job that was intended to humiliate him as a Jew.

He came to be called “the pig-man.”

Israel Steinberg.

…

Ludwig Juliusberger was taken to Breendonk on November 11.

Born in Berlin, he informed the other prisoners in Room 1 that he had studied law and worked as a journalist publishing anti-Nazi pamphlets before fleeing to Austria and then France. He also told them that once he arrived in Belgium, a background check by immigration officials revealed that he had fought in the German army during World War I. Because Belgian authorities suspected him of being pro-Nazi, he, like many other native Germans living in Belgium, was arrested and placed in prison.

Ludwig Juliusberger.

Of course, an inmate could tell other prisoners anything; the truth of any story could not be verified. Although Juliusberger claimed to be a journalist, his police records suggested another story. When Belgian authorities checked his background in Germany, they discovered that before 1932 he had been charged twelve times for forgery, fraud, gambling, and embezzlement. On September 1, 1939, five days after he arrived in Belgium, he was arrested for fraud. He had checked in to a series of Brussels hotels using false names and then left without paying his bill. A Belgian court had sentenced him to fourteen months in jail for fraud—not for being a former soldier in the German army.

By the time his sentence was completed, Belgium was controlled by the German military government, and because Juliusberger was a Jew, Breendonk was his next stop.

He became prisoner number 34.

Paul Lévy.

…

Paul Lévy, a well-known Belgian radio personality, left Belgium during the eighteen-day invasion, with other employees of his radio station. Warned by his friends not to return because of his Jewish heritage, Lévy ignored their advice. Instead, when he went back to Belgium on July 8, he converted to Catholicism, because of “his beliefs and love for his wife.” Soon after, he told German authorities that he would not read the heavily censored and propaganda-filled pro-Nazi news on the radio. After this act of defiance, he was arrested. He arrived at Breendonk on November 29 and was herded down the entrance tunnel to the courtyard, where he was ordered to face the wall.

There, SS-Lieutenant Prauss asked the four prisoners who arrived that day, “Who is a Jew here?”

After the others replied, Lévy, well aware that his recent conversion to Catholicism would not save him, answered, “According to my point of view, no . . . according to yours, surely yes.”

Prauss looked at Lévy, shrugged, and then struck him across the face.

When it was his turn to receive his uniform, Lévy was given number 19 and sent outside to work, shoveling dirt into a wheelbarrow. As he attempted to do this, SS-Major Schmitt kicked him three times. Lévy vowed that he would somehow gain his freedom and tell the world about Breendonk.

Lévy believed that his days at the camp would be limited. Unlike the other prisoners, his head had not been shaved the first day. He hoped this was a sign that he was not a long-term prisoner and would be released soon. The next day, however, he was taken from his wheelbarrow and told to run to the courtyard. There, a prisoner waited for him with a razor.

Because Lévy had a thick head of hair, a Wehrmacht guard said, “What filth! There must be lice in this forest.”

In less than five minutes, Lévy’s head was bare, and the reality of a long stay at Breendonk had begun to set in.

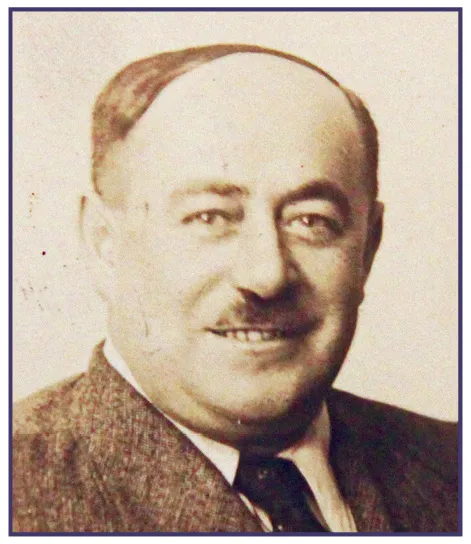

Oskar Hoffman.

…

Oskar Hoffman, who arrived on December 5, was assigned to be the first blacksmith at the camp. An Austrian citizen, he and his wife fled to Belgium a few months after the Anschluss. When the German invasion began, Hoffman was arrested by Belgian police for fear that he might be an enemy agent and he was deported to an internment camp in southern France. When he eventually returned to Belgium, an acquaintance from the French camp, perhaps trying to garner favor, informed authorities that Hoffman held anti-Nazi sentiments.

As a result, Hoffman was arrested and sent to Breendonk, where he became prisoner number 17.

…

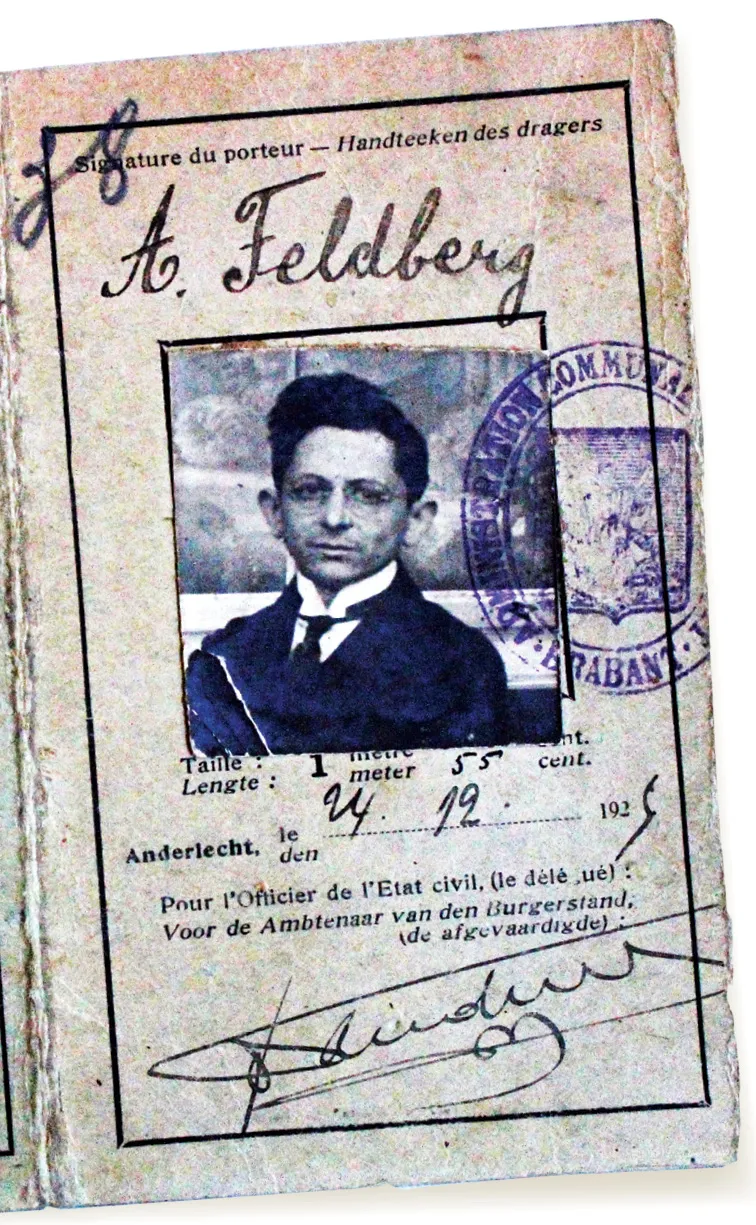

Abraham Feldberg arrived on December 7. Feldberg was a Polish immigrant who had a popular shop in Arlon, a small town in southeast Belgium near the Luxembourg border, where he sold suspenders and other items made from elastic. Sometimes he dressed in a clown costume with a large bowler hat and acted like a buffoon to attract shoppers to his store.

Abraham Feldberg, as shown on his 1929 Belgian identity card.

On October 28, the Militärverwaltung enacted a law that required Jewish merchants to display a poster indicating their store was a Jewish business. To comply with this regulation, Feldberg decided to poke fun at it by posting three signs on his front windows. In a report written after the war, an inspector for the town of Arlon noted that not only did Feldberg’s large signs irritate the Germans, but his gestures toward the signs also were “not to the Germans’ taste.”

Not long after, he was arrested and sent to Breendonk, where he became prisoner number 53 and the camp’s first shoemaker.

…

No matter which color ribbon the prisoner was made to wear, the inmates at the fort had a common confusion. They were almost always never told why they had been arrested. They were almost never tried for a crime. They were almost never given a specific sentence to serve.

They were simply locked up and kept in a terrible limbo, waiting for whatever would happe...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Frontispiece

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Map of Belgium during World War II

- Plan of Breendonk, c. 1943

- Definitions of Terms Used in This Book

- Introduction

- The First Prisoners September–December 1940

- The Arrest of Israel Neumann

- Building Breendonk

- Facing the Wall

- The First Prisoners of Room 1

- The Artist of Room 1

- Watching the Prisoners

- The Zugführer of Room 1

- A Day at Breendonk

- The First Deaths January–June 1941

- Changes

- The First Escape

- Despair

- A Picture-Perfect Camp

- Camp of the Creeping Death June 1941–June 1942

- Operation Solstice

- Prisoner Number 59

- A Substitution

- The Rivals

- The Plant Eaters

- July 24, 1941

- The Hell of Breendonk

- The First Transport

- A Temporary Lull

- A Second Camp July–August 1942

- The Sammellager in Mechelen

- Transport II to Auschwitz-Birkenau

- Camp of Terror September 1942–April 1944

- The Postal Workers of Brussels

- The First Executions

- The Arrestanten

- The Bunker

- January 6, 1943

- The Winter of 1942–43

- Transport XX

- The Chaplain of the Executions

- Two Heroes of Breendonk

- The Twelve from Senzeilles

- The Many Endings of Auffanglager Breendonk May 1944–May 1945

- Evacuating Breendonk

- Journey from Mauthausen

- End of the Supermen

- The Final Transport from Neuengamme

- After the War 1945–Present

- The War Crimes Trials

- The Final Death

- Breendonk Today

- Afterword

- Appendices

- Quotation Sources

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Illustration Credits

- Index

- About the Author

- About the Photographer

- Connect with HMH

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Prisoners Of Breendonk by James M. Deem in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.