![]()

PART I

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Well-Being

![]()

Overview Essay

by Neva R. Goodwin

As an overview and introduction to the topics of the whole book, Part I will give examples of an ongoing dialogue between philosophy and economics in which the former poses the “big questions”—What is the good life? What is happiness? What is well-being?—while economics, even in its most philosophical mode, rarely goes beyond the narrower question: What is economic well-being (or material prosperity, or a good standard of living)? The purpose of this overview essay is to present this dialogue in such a way that the reader can make a solid start on our larger project: to explore the notion of well-being and its relationship to economic concepts and concerns.

The essay will begin with two fairly abstract sections. The first will present three different ways in which one might understand how economic growth relates to human well-being. The second section will indicate how the term economic growth is being used here, while providing some definitions for that concept and for human well-being.

With these frameworks in mind, the next section will raise a topic that will recur throughout this book: the issues of measurements and indicators. How much do we actually know—in a “scientific” manner—about well-being? The answer is that there has been real progress in this area of study. Some conclusions will be cited, going beyond the works summarized here. The final section will emphasize what philosophy has to contribute to the question of how economics should define its concerns.

Abstractions Rendered Visually: Three Worldviews

As a starting point for thinking about the interface between the philosophical and economic questions cited above it will be useful to consider some schematic frameworks for our subjects.

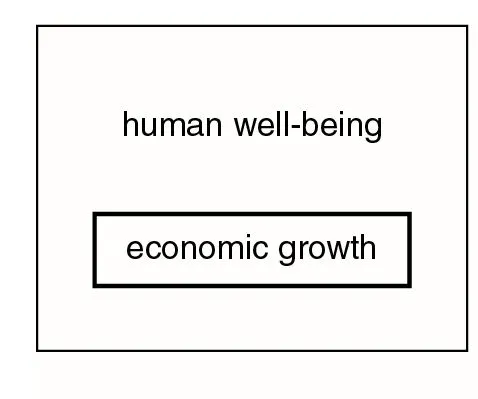

Figure 1 and the two figures to follow may be understood as depicting three different worldviews. In Figure 1, economic growth is seen as a subset of human well-being; the larger set also contains and depends on other things than economic growth. However, the diagram implies that wherever economic growth occurs it will always contribute to human well-being. This position may be associated with major personalities in the history of economic thought, such as Alfred Marshall, who said that economics “examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of well-being.”1 Marshall would evidently have accepted Figure 1, assuming a relatively broad definition of human well-being, or social welfare, as a framework for the economic welfare that depends on economic growth.

Figure 1. All Economic Growth Contributes to Well-Being.

Figure 1 represents the core of what is now the standard neoclassical economic model, which defines its goal in terms of utility maximization achieved through optimal resource allocation, depending on free exchange in which rational, selfish individuals trade in a competitive market.

The neoclassical approach was sharpened by the concept of “revealed preferences,” a concept that grew out of a perhaps too-ready conclusion that utility is scientifically unobservable. (See the Overview Essays to Parts III and V for more on revealed preferences.) The fallback (carrying positivism to its logical extreme) was to say that all we can scientifically know about people is their actions. Purchasing behavior is the “preference revealing” type of action that economists choose to emphasize (thereby significantly overrepresenting consumers at the expense of workers). “Utility,” “satisfaction,” and “happiness” are thus identified with the purchase of marketed goods and services.

The revealed preference model does not logically have to be interpreted this way, though it is often used to generate an especially restricted worldview where human well-being entirely depends on economic activity. Worse yet, the only aspect of economic activity that is expected to contribute to human well-being is the satisfaction of consumer wants and preferences. This model gives no regard to the experience of human beings in their other economic roles as producers, regulators, merchandisers, etc. (let alone other human roles, such as citizens, parents, and so on).

Jerome Segal, in the first paper summarized in this section, proposes the term instrumental consumptionism for the view that assumes that the overwhelmingly dominant aspect of economic growth is increased consumption. An example of a weak version of instrumental consumptionism may be found in the second paper summarized in Part I. The author, Tibor Scitovsky, notes that it is impossible to aggregate individual, subjective preferences into a global or social preference if we are dealing with “the entire range of human needs and desires.” 2 However, he identifies a large subset (“the greater part of that range”) that “comprises all the needs and desires that consumer goods and services can satisfy”—that is, “the goods and services that are separable and saleable piecemeal to individuals though consumer markets.”

For reasons that were explained in the Volume Introduction, the summaries in this book represent relatively few proponents of the dominant Figure 1 worldview. The position of the editors of this book, and that of many of the writers summarized in this volume, is better to be found in Figures 2 and/or 3.

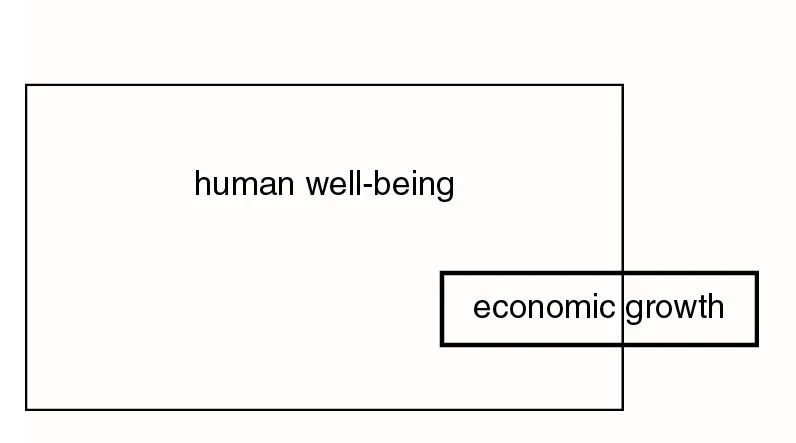

As in Figure 1, we can find in Figures 2 and 3 the assumption that economic growth is a smaller set than human well-being. However, here the two concepts are portrayed as overlapping sets: not only are some parts of human well-being untouched by economic growth, there are also some parts of economic growth that lie outside of—i.e., do not contribute to—human well-being.

The difference between them is that in Figure 2 all aspects of economic growth that lie outside of the larger set are neutral in their effect on human well-being. Figure 3 depicts a different belief. Here the picture is complicated with the inclusion of another set, of “detriments to human well-being.” This is relevant to Figure 3 because the worldview depicted here conceives of some aspects of economic growth as lying within the “detriments” set; aspects of economic growth (in the shaded area) not only do not contribute to, but actually detract from the more general human well-being.

Figure 2. Some Economic Growth is Neutral with Respect to Well-Being.

Figure 3. Some Economic Growth May Detract from Well-Being.

When economic growth causes pollution, this would be an aspect of economic growth that lies in the shaded area. Other examples might include an increase in selfishness or a breakdown in community when the value of acquiring wealth is elevated above many other human values; or the destruction of indigenous communities through resource exploitation by global corporations; or the legal sale of tobacco and other health-harming products.

Some criminal activities will also turn up in the shaded area. Many of them do contribute to economic growth—consider the billions of dollars that flow on the black markets for illegal drugs and weapons—but they are illegal because society considers them harmful to human well-being. Laws can change: gambling or lotteries may be legal at one time, then become illegal, and then again be legalized. We could subdivide the shaded area into “legal” and “illegal” portions; then we may find some economic activities associated with gambling or drug use moving over the dividing line between legal and illegal, while still staying in the shaded area.

Definitions and Lists (and More Questions)

The topic of this book is the relationship between human well-being and economic goals. The three figures shown so far have dwelt on economic growth as a way of leading into economic goals. As we consider what can be learned from these renderings we will need some definitions.

As a start, let us say that by “economic goals” we mean the goals of economic policy, and the goals assumed in economic theory. Now, with the three figures in mind, we can ask: (1) Should economic goals be limited to the achievement of economic growth?, and (2) Are there aspects of economic growth that should not be included within our economic goals?

More definitions are still required. Drawing on our earlier quotations from Marshall and Scitovsky we may approach “economic growth” by saying that it consists of an increase in the production, for exchange in a market, of the goods and services for which there is effective demand. This, then, is the activity—this increase in production for market exchange—about which we are asking: (1) Is this a sufficient goal for economic policy and theory?, and (2) Is it possible, or likely, that such an increase will sometimes detract from human welfare?

If the last answer is Yes, we might then add another question: (3) How should economic theory and/or policy adapt to such a possibility? That is an extremely important issue, which will only be touched on in a few places here. (This question was also raised in Frontier Volume 2, The Consumer Society.)

To complete our definitions we still need to address the broader issue of what we mean by “human well-being.” “Social well-being” or “social welfare”3 are topics that, for a while at least, received a good deal of attention in the economics literature. If we could find good definitions for these terms we might be able to use or revise them for our present purposes. Unfortunately such an effort only illustrates the difficulties attending our present search. These difficulties are laid out in the MIT Dictionary of Economics entry on “Social Welfare,” which it defines as “The well-being of the society or community at large.” The entry continues as follows:

In defining social welfare we face two sets of problems. The first problem concerns the “social” aspect. In general, social welfare is seen as some aggregation of the welfare of individual members of society—this raises the question of how the aggregation is to be achieved. The second problem relates to the concept of “welfare.” I. M. D. Little has argued that “welfare” is an ethical concept since to define something as contributing to welfare is to make a value judgment about whether that thing is good or bad. Alternatively it has been argued that welfare should be equated with the satisfaction of individual preferences and regarded as a “technical” term. On the whole, Little’s argument is more widely accepted and definitions of social welfare are usually regarded as value judgments.4

The technical approach to social welfare that is de-emphasized here is, presumably, revealed preferences. The choice is presented fairly starkly: either conclude that purchasing behavior is all that matters (because it is all that we can know) about social welfare; or else give up on any attempt at science and conclude that broad definitions of welfare must be left to the realm of value judgments.

Fortunately, there is more that can be said. Some thinkers have approached a definition of human well-being by composing lists of the elements that go into it. Two such will be cited here.5 Robert Lane, a political scientist who has written extensively on this topic, states that the maxims for a social science should be “subjective well-being” and “human development,” where the first of these can be divided into the components of “happiness” and “satisfaction with life as a whole,” while the second is composed of “cognitive complexity,” “self-attribution,” and “self-esteem.” His treatment of these subjects in the book The Market Experience contains much that is interesting and thought-provoking, but is more suggestive than incisive in defining these terms.6

Another take is found in the article by John Oliver Wilson summarized in this section. In a helpful distillation he, like Lane, identifies two “social goals”—individual happiness and economic justice—and then lays out the “social values” of which each is composed. He also lists the “socioeconomic outputs” required to achieve these social values, thus7:

| Social goods | Social values | Socioeconomic outputs |

| Individual happiness | • Sustenance | • Basic economic essentials |

| • Quality of life | • Economic security |

| • Participation | • Equal opportunities |

| | • Respect, acknowledgment |

| Economic justice | • Equity | • Commutative justice |

| • Fairness | • Productive justi... |