Edward Hazel was worried about the end of the world. A veteran who had served his nation in Korea, he was now a father of two living a quiet life in rural midwestern Ohio and facing the troubling prospect that the war had followed him home. In October 1961, news from Berlin dominated the airwaves, and Hazel decided it was high time to write a letter to the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (OCDM) asking, as any concerned parent might, for help and advice on how best to “educate and protect his family from the threat of nuclear war.”1 Like Art Carlson, he had decided to follow the advice of his president and build his own private fallout shelter. His letter to the OCDM does not record details about how much his chosen shelter cost, how difficult it was to assemble, or what other survival tools he purchased.2 Rather, he wrote about his children—specifically, his worry that they did not seem to take the threat of nuclear war as seriously as he did. “They must learn because it is necessary, but I must tell you it’s not easy. I want to teach them but it’s tricky. I guess this is something you can’t force.” He continued: “We live in an age of war. . . . [I]n a world created by these weapons, anything I can do to protect my family must be done. I believe in shelters. My kids do not.” For Hazel, building a fallout shelter was not just “a service to his nation” but also his duty as a parent. Closing his letter with a request for more educational material, he asked the OCDM to “please advise a troubled citizen and a worried father.”3

Edward Hazel’s letter, buried for many years in the regional records of the OCDM, hints at the complex interplay between cultures of Cold War paternalism and the domestic practice of shelter construction. In this case, the obligation to be a responsible father entwined with the defense of the nation. While Hazel’s letter does not fully represent the experiences of millions of families across the United States as they confronted the prospect of a nuclear war, it does provide a glimpse into some of the personal dilemmas that confronted fathers who were prepping their families for the last war. The family fallout shelter was a powerful symbol for men such as Hazel, who were fraught with anxiety about a world that seemed to be spiraling toward nuclear disaster. It became a site of both action and impotence, a domestic arena in which to perform a politicized model of Cold War fatherhood, a constant reminder that every citizen was a soldier, every family a target, every home minutes away from being obliterated. Hazel’s letter demonstrates that the boundaries enclosing shelters and fatherhood were neither static nor stable. As he and other fathers struggled to implement state-sanctioned, do-it-yourself survival, they often found themselves questioning the accepted construct that a nuclear war was conventionally winnable. In other words, when facing the prospect of building a family fallout shelter, such fathers came face to face with the potential limitations of their paternal power.

To understand Hazel’s experiences, we must first consider the political history of the fallout shelter father. Building a shelter, protecting the family, believing that home defense might be a viable solution: these were constructed narratives of masculinity created by the political imperatives of the national security state. Since the detonation of the Soviet atomic bomb Joe 1 in 1949, American national security advisors had been fearing that, at any moment, the Cold War might turn hot. But how, in this age of total war, were ordinary citizens to be protected? The unenviable task of answering this impossible question fell to the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA, which later became the OCDM). Equal parts hopeful and cynical, its policymakers spent much of the 1950s informing the public that the solution to survival rested in their own hands and in the actions of their families. By 1961, when Hazel wrote his worried letter, public education campaigns had been telling him for more than a decade that it was his duty to cooperate with the policies of home survival.

America’s Missing Shield

On October 4, 1957, a few years before Hazel wrote his letter, President Dwight D. Eisenhower received a message that sent shockwaves through the National Security Council (NSC). After arriving in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, for a relaxing weekend of golf, he was informed via telephone that the Soviet Union had fired an R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) from a silo in the Kazakhstan desert, successfully launching into orbit a small aluminum sphere, twenty-two inches in diameter and weighing 184 pounds.4 Known as Sputnik, the diminutive missile’s impact on U.S. national security was enormous. As George Reedy, an assistant to Senate majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson, declared, “Like a brick through a plate-glass window, it shattered into tiny slivers the American illusion of technical superiority over the Soviet Union.”5 Sputnik’s successful launch seemingly confirmed two things: first, that at the tail end of 1957 the Soviet Union had achieved dominance over the United States in rocket technology; and, second, that it could theoretically launch a preemptive strike against mainland America.

Speaking later that week on the television news program Face the Nation, Edward Teller, a theoretical physicist and ardent militarist known as the father of the hydrogen bomb, told his audience that “this week the U.S. has lost a battle more important and greater than Pearl Harbor.”6 Teller’s melodramatic warning may have exaggerated the technological significance of Sputnik, but it heralded a shift in strategic language and presented a conception of U.S. vulnerability that would shortly become a running debate in the halls of the Pentagon. Soon, Senator Johnson warned, the Soviets “will be dropping bombs on us from space like kids dropping rocks onto cars from the freeway.” He concluded, simply, that “something has to be done.”7 With Sputnik in orbit around the earth, the reality of nuclear war came crashing into living rooms across America.

How should U.S. defense planners respond to the challenges posed by Sputnik? Was the time right for a national program of government-funded community shelters? Should local authorities ensure that the key metropolitan target zones had plans for mass urban evacuation? Should even more destructive nuclear weapons be developed to ensure that the United States could maintain its overwhelming superiority in destructive power? As C. D. Jackson, government propagandist and senior executive at Time Inc., said, “the impact of Sputnik” on the national psyche was “overwhelming. . . . I repeat overwhelming.”8

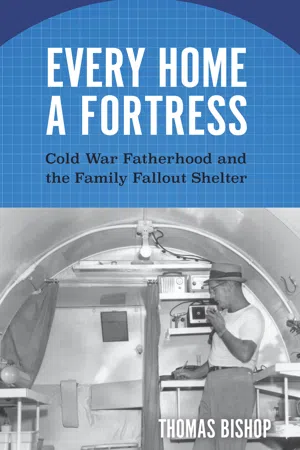

Facing what the historian Michael S. Sherry has described as an “intense demand for an active homefront defense,” Eisenhower surprised his critics.9 The Gaither committee, a group of civilian strategists tasked with advising the administration on how best to prepare the nation for a nuclear strike, had recommended a new $40 billion system of national community shelters, but the president opposed it. Instead, he devised a new strategy of atomic survival, one shifting civic duties onto the shoulders of ordinary families. Billing the idea as a program of do-it-yourself survival, the administration declared that the best chance of surviving a preemptive Soviet nuclear strike lay in the behavior of individuals, the fortification of suburban homes, and the preparation of families. Fathers were instructed to build shelters, mothers to stock kitchens with canned goods, and children to watch out for a bright flash of light on the horizon. Every home should become a fortress.10

News of Sputnik’s launch was not all doom and gloom. As questions circulated in the national press about the administration’s ability to defend its citizens, Leo Hoegh, soon to become head of the OCDM, was presented with what he saw as a “unique opportunity” to “reverse the fortunes of civil defense.”11 Removed from the portfolio of the National Security Resource Board in 1950, the civil defense brief had since become political driftwood in Washington.12 Persistently underfunded by Congress, unpopular with experts at the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), and routinely ridiculed by cynical sections of the national press, policymakers had repeatedly watched their ambitious nationwide programs be pushed to the sidelines or left off the planning agenda.13 “When you mention that you work for civil defense in those tiresome parties on Capitol Hill,” Hoegh noted in his private papers, “people tend to raise an eyebrow, before changing the conversation.”14 Now, at the end of 1957, the scales had tipped, for the first time, toward the OCDM policymakers. It was their moment to push discussions of civil defense to the front of the national agenda.

While Hoegh was looking for ways to make civil defense a more appealing prospect to DC’s movers and shakers, Eisenhower was embroiled in his own institutional battle. As the historian Stephen Ambrose notes, in the months preceding the launch of Sputnik, the president had faced numerous demands to increase military spending yet “refused to bend to the pressure, refused to initiate a fallout shelter program, refused to expand conventional nuclear forces, refused to panic.”15 Sputnik’s launch had been, according to the Cold War scholar John Lewis Gaddis, “a deliberate effort on Khrushchev’s part to extract political advantage from the demonstration of long-range missile capability,” and it was forcing Eisenhower to work tirelessly to “dampen hysteria and resist militarization.”16 This was no easy feat. News coverage was claiming that the president’s relative passivity was analogous to the situation before the attack on Pearl Harbor, when executive inaction had cost the nation dearly.17

Writing for the Washington Post, the journalist and DC insider Stewart Alsop sardonically compared Eisenhower’s response to the Sputnik launch to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1938 hesitation as Britain began implementing a policy of appeasement toward Germany.18 Eisenhower’s Democratic rivals, expertly riled by Senator Johnson, worked to gain political capital as they attacked the president’s lackluster defense program. With the 1958 midterms approaching and no clear Democratic frontrunner for the 1960 election, Johnson launched a series of scathing public attacks about a “weak willed” and “passive” president who appeared to be impotent in the face of Communist scientific advancement.19 Calling for a reactivation of the Preparedness Subcommittee, the senator made it clear that both the nation and the president were ill-prepared. In the pages of the New York Times, he lambasted Eisenhower’s “record of underestimating the Soviet program” and his historic “lack of willingness to take proper risks.”20 In this new missile age, Johnson argued, vigor, determination, zeal, and self-sacrifice were necessary. Now was “not the time for a failure of nerves. It [was] a time for action.” While members of Congress offered little concrete evidence of what exact form this “action” should take, they were clear that the Eisenhower administration needed to disseminate a public message about the state’s obligations to ensure its citizens’ survival. Eisenhower’s inner circle tried to downplay Sputnik’s impact but had little success. When Percival Brundage, a key ally and the director of the Bureau of Budget, mentioned to the Washington socialite Perle Mesta that Sputnik would be “forgotten in six months,” she simply said, “Yes, dear, and in six months we may be dead.”21

In the months following the launch of Sputnik, do-it-yourself survival became the watchword of civil defense, and in the winter of 1957–58 various policy positions began to solidify around the idea that private shelter construction was the most cost-effective solution for the dilemma posed by the growing Soviet nuclear threat. Eisenhower’s stance was not just a product of the Sputnik moment but was rooted in a long-running discussion within the national security establishment about what exactly comprised the state’s duty to protect its private citizens.

Throughout the early 1950s discussions about what to do if the bomb dropped were a persistent, troublesome refrain in U.S. strategic thought. In the symbol-driven politics of the Cold War, the desire to strike a balance between toughness and aggression made civil defense a contentious topic during NSC meetings. In this new missile age, what should the American home front look like? More importantly, how should it differ from the Soviet Union’s? Several politically savvy members of the FCDA—among them, Edward Lyman, the director of civic affairs; William Heimlich, the head of public affairs; and Katherine Howard, the agency’s vice-chair under its director, Val Peterson—had long claimed that, if presente...