![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Overview and Introduction

Two quotations seem apt for introducing Stewardship of the Built Environment , an approach emphasizing reuse and preservation of our existing building stock. The first, “problems cannot be solved with the same level of awareness that created them,” by Albert Einstein, encourages examination of an underused path to seeking solutions to sustainability. As we find ourselves on an increasingly resource-depleted planet with a changing climate, we must rethink how we build and develop. Many people have become so accustomed to creating new things that the idea of reusing or adapting something that already exists is new to them. In the particular instance of the built environment, however, the sustainable solution may not lie solely in creating new green buildings but rather in recognizing a new way of looking at the problem and seeking a potentially overlooked solution through retrofit, reuse, and preservation.

The second quotation is by Marcel Proust: “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” In this instance the new landscape literally and figuratively encompasses the increased sustainability of our built and natural environment. In reflecting on the meaning of these two quotes, the concept of stewardship of the built environment emerges as a valuable approach to increasing sustainability.

This chapter introduces the concept of stewardship of the built environment and provides an overview of how preserving and reusing buildings can be a viable strategy in crafting a sustainable built environment. It explains the antecedents that stewardship has drawn from the social, environmental, and economic contexts of the past and offers a look at the contemporary and future implications of pursuing this philosophy. Upon reading this chapter, you will have ample context for the detailed observations, arguments, and examples of stewardship of the built environment addressed in the rest of the book.

Stewardship of the Built Environment

Stewardship of the built environment is a philosophy (box 1.1) that balances the needs of contemporary society and its impact on the built environment with their ultimate effects on the natural environment (Young 2008a: 3). The goal of stewardship is to merge the reuse of the built environment with environmental conservation and to take advantage of innumerable opportunities that foster a more sustainable environment. Thus, this approach recognizes the value of reusing existing buildings to avoid the impacts that new building construction can create, both directly and indirectly, and also as a means to do the following:

- Decrease the long-term extraction and depletion of natural resources

- Abate the landfill pressures caused by the unnecessary demolition of buildings

- Reduce the consumption of energy used in demolition and the compounded effects of the embodied energy needed to create new or replacement buildings

- Reduce the creation of green sprawl

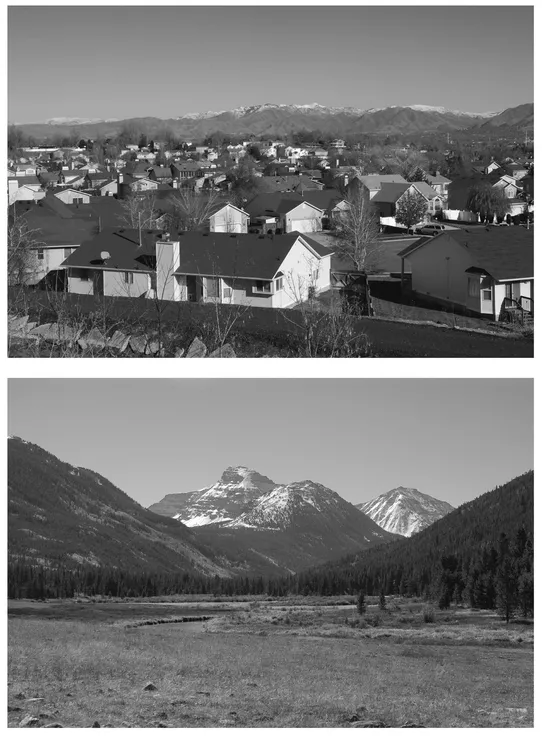

- Reduce the social, environmental, and economic costs associated with suburban expansion and land use intensification (fig. 1.1)

Conversely, stewardship of the built environment can foster long-term revitalization of the urban core by rehabilitating existing buildings to reestablish vibrancy in a community, district, or neighborhood. This vibrancy, which stems directly from a well-balanced approach to meeting the social, environmental, and economic concerns of the contemporary and expected demands of our population, is critical to the attainment of a sustainable society.

In the late twentieth century, a more holistic view of the impact of reusing buildings emerged from efforts to understand how existing buildings can go beyond the singular premise of energy efficiency and continue to contribute to the overall sustainability of the built environment. Most notable were the findings in Our Common Future, published by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) and commonly referred to as the Brundtland Report, which concluded that sustainability is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED 1987: 43). Advocates for preserving and reusing buildings recognize that this approach complements sustainability efforts by demonstrating that the reuse of a building affects a broader view of the environment that extends into the effects on future generations. Preservation and reuse results in consumption of fewer resources than new construction and also helps moderate sprawl and its attendant negative impacts on social, environmental, and economic conditions.

Box 1.1

Stewardship of the Built Environment Principles

Stewardship of the built environment recognizes that the preservation, rehabilitation, and reuse of existing older and historic buildings contributes to sustainable design; respects the past, present, and future users of the built environment; and balances the needs of contemporary society and its impact on the built environment with the ultimate effects on the natural environment.

The built environment is a subset of the overall environment and should symbiotically interact with the natural environment (i.e., what affects one will ultimately affect the other, either negatively or positively). Therefore, the guiding principles include the following:

- Sustainability is the integral and balanced combination of social, environmental, and economic forces.

- Reusing a building is the ultimate form of recycling. Demolishing a building increases landfill pressures and intensifies demands for new raw materials to create new building components.

- Preservation and reuse conserves existing social, environmental, and economic resources while revitalizing buildings, neighborhoods, and communities.

- Although retaining every building is not practicable, sensible efforts must be made to avoid unnecessary demolition or wasting of built resources.

- Accepting new land uses that preclude the preservation or reuse of the existing built environment, promote increased use of nonrenewable energy sources, or impose increased social, environmental, and infrastructural costs is inherently unsustainable.

- Beyond the footprint of a single building, ecological performance can be improved through land use strategies that complement the sustainability of a building or site at the local and regional level, such as public transit, bicycles, and walking, that reduce automobile dependency and the number of vehicle miles traveled using nonrenewable fuel sources.

Figure 1.1. Stewardship of the built environment considers contemporary and future needs of society and balances those needs with their impact on the natural environment. The philosophy recognizes that a critical part of that balance is reuse of the existing built environment to reduce growth pressures and their impact on the natural environment.

Stewardship of the built environment occurs as part of sustainable design where three factors—social (S), environmental (E), and economic (E)—optimally interact with one another. These factors comprise what are often called the three pillars of sustainable design, or the SEE approach to sustainable design. Stewardship of the built environment happens within this sustainable design region of the overlapping systems, taking into account the broader impact on the overall environment, in addition to the specifics of a single site or project.

The SEE approach, described herein, captures the singular definition of the Brundtland Report and broadens the perspectives of the social, environmental, and economic factors both separately and synergistically. Given the frequency of discussions about sustainability, the actual widespread adoption of a single descriptive phrase remains in flux; variations that describe sustainability in terms of “people, planet, and profit” (PPP), “ecology, ethics, and economics” (EEE) (Daly and Townsend 1993), and the “triple bottom line” (TBL) (Elkington 1998) are also in common use today. Although the exact words are different, they are essentially the same concepts.

Application of SEE to the Built Environment

The SEE approach can be a guide to improving the built environment by preserving and reusing existing buildings, redeveloping degraded sites, and building new infill construction instead of expanding the built environment with new construction in the suburban periphery. Development and growth that take place within the existing building stock—whether historic or simply old buildings—can mitigate further degradation of the local (and, in aggregate, the global) environment. The often overlooked crux of the matter is that construction of new “sustainable” buildings on the suburban periphery entails investment of significant energy resources, may contribute to increased air pollution via automobile-only access, and also may increase the societal costs of public infrastructure and cultural isolationism. Strictly adhering to a new-construction-only approach also has global implications because the use of new materials (i.e., no recycled content) has cumulative impacts on the social fabric, environmental integrity, and the economy as natural resources are extracted, processed, transported, and installed in the building.

Recycling metals, glass, paper, and plastics and the broad societal gains that recycling fosters have gained attention over the past decade. Let us for a moment consider that reusing a building is the ultimate form of the mantra “reduce, reuse, recycle.” In recognizing stewardship of the built environment as a significantly larger-scale application of this simple holistic strategy, we can expect building preservation and reuse to have significant implications for reducing social, environmental, and economic pressures and thereby increasing sustainability along the entire spectrum of building design, construction, use, and operation. As a consequence, we need to take a more enlightened look at how we preserve and reuse our built environment by reinvesting in and retrofitting existing buildings to meet contemporary and future needs of society.

The philosophy of stewardship of the built environment draws from the recognition of these tenets:

- The greenest building is one that is already built (Elefante 2007: 26).

- Newly constructed buildings do not save energy immediately (Jackson 2005: 45–52).

- Demolishing existing buildings and replacing them with new buildings that increase overall ecological impacts is not sustainable (Young 2008b: 57–60).

- Recent quantification metrics and assessment systems provide a mechanism to evaluate overall sustainability (Campagna 2008: 1–2, 6).

- Sprawl, even green sprawl, is a threat to sustainability (Shapiro 2007).

The first statement here, that the greenest building is one that is already built, makes the point that money, energy, and material resource savings have often revealed that reuse of an existing building has a number of sustainable qualities that are overlooked in the continued perception that we can use new construction to build our way to sustainability.

Over the past few years, a more comprehensive look at the life cycle analysis of a building that includes nonenergy impacts such as carbon and water consumption has been gaining favor. In this approach, alternative choices are compared based on the avoided impacts of design choices. Several studies conducted by the Athena Sustainable Materials Institute in Canada have demonstrated that preservation and reuse of buildings often provides the most sustainable outcome of project options when compared with constructing a comparable new building.

One of the more complex issues to understand is that although newly constructed green buildings are designed to use less energy than those from the late twentieth century, the overall process of constructing these new green buildings does not immediately save energy. This is because no true energy savings accrue until the energy used to create the new building is recouped. So although a new building may consume energy at a lower rate than an existing building, it must overcome the energy deficit generated before it actually saves energy in comparison to reusing a building. The environmental impacts are further exacerbated when a building is demolished to make way for the new construction. As noted in The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse, “it can take between 10 and 80 years for a new energy-efficient building to overcome, through more efficient operations, the negative climate change impacts that were created during the construction process” (Preservation Green Lab 2012: iv). When existing buildings are replaced with new construction, energy deficits increase substantially because of the energy used in the demolition (and some will argue for recognition of the wasting of the embodied energy, water, and carbon used in the original construction of the building as well). Also, demolition debris increases pressure on landfills. With demolition debris accounting for nearly 40 percent of current landfill volumes, this impact is significant.

The construction industry has been steadily increasing the recycling of base materials with such programs as Habitat for Humanity’s ReStore program (Habitat for Humanity 2012). However, until a component and material reuse industry develops that looks to comprehensively reuse building materials at their same level of use (e.g., salvaging) and moves beyond the current recycling approach that downcycles building materials (e.g., grinding up materials to be used as filler in other construction products), the practice of demolishing existing buildings and replacing them with new ones will remain an inherently nonsustainable enterprise. This is where the life cycle analysis approach plays an increasingly important role in determining the true sustainability of a building design and construction decision.

Concerns about misinformation and, perhaps, misrepresentation of sustainability (i.e., green-greenwashing) prompted the development and introduction of more comprehensive sustainability metric systems and assessment tools by the end of the twentieth century. The concept of energy efficiency was embraced by proponents of the environmental movement and eventually evolved into the current sustainability movement. While people, companies, and organizations attempted to increase the sustainability of the built environment, competition in the market motivated some to engage in greenwashing (e.g., to extol their qualities as green when in fact the validity of their claims was suspect). As a result of this abuse, demand grew for a systematic way to quantify how green or sustainable a building was when completed and eliminate greenwashing practices. Initially, the creators of these rating systems focused on what new construction could do to become more sustainable, and it was not unexpected to see many quantification methods addressing primarily new construction.

Although there are many quantification systems worldwide, the current leading program in the United States is the US Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LE...