This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This timely and interdisciplinary volume analyzes the many impacts of and contrasting responses to the Argentine political, economic, and social crises of 2001-02. Chapters offer original theoretical models and examine the relationship between political, cultural, economic, and societal spheres.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Argentina Since the 2001 Crisis by C. Levey, D. Ozarow, C. Wylde, C. Levey,D. Ozarow,C. Wylde in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Political Economy of (Post)Crisis Argentina

Chapter 1

Continuity and Change in the Interpretation of Upheaval: Reexamining the Argentine Crisis of 2001–2

Christopher Wylde

The multiple-faceted crisis of 2001–2 had many long-term consequences for Argentina’s political economy and subsequent trajectory of development, as well as on a whole range of other issues from forms of social organization and resistance to cultural and literary responses. In the immediate aftermath, debates that attempted to explain the origins of the crisis tended to be presented in terms of the severe macroeconomic, political, and social consequences. Over a decade has since passed, and Argentina has transformed its political economy and experienced sustained economic growth; emerging from its status as an international pariah as part of a wider continental shift in political economy following the election of a series of left-wing governments throughout the region, which has come to be known as the “pink tide.”

This impressive postcrisis economic performance has come under threat in recent years. First, international factors have been influential. The onset of systemic and ongoing recession in the Advanced Capitalist Countries (ACCs) has had a series of dramatic impacts on the global economy from slowing levels of international trade to the role of historically low interest rates set by the US Federal Reserve. Second, a series of perhaps more endogenous social issues have arisen during the presidency of Cristina Kirchner. Criticisms that have been leveled against her government include flawed policies pertaining to taxation and import restrictions, through to more personal attacks on the “first family” itself over alleged irregular personal wealth accumulation while in office. These factors have all facilitated the impression of a country at an important crossroad as it attempts to complete the transition from a postcrisis to a normalized economy.

This chapter provides an important compendium of the analyses and debates that have surrounded the crisis in Argentina and its legacies since 2001. In so doing, it will demonstrate that many commentators have framed their contributions (explicitly or implicitly) within the false dichotomy of “old” and “new.” In other words, previous models of political economy are used as heuristic devices for their explanation of the origins of the country’s implosion. This chapter will show that this reductionist approach leads to at worst an inappropriate and at best an incomplete understanding of 2001 and the subsequent decade.

In the context of this chapter, analysis of the 2001–2 period draws on both elements of continuity and elements of change from a range of historic forces present in Argentina to explain its roots, responses to it, and trajectories of recovery, with particular reference to previous development models in the country’s recent past and political economy. In order to facilitate this approach, this chapter divides explanations under three broad groupings. First, those that center on explanations that concern fiscal policy and Argentine debt (see, e.g., Mussa 2002; Schuler 2002); second, those that center on investor speculation and growth prediction expectations (see Stiglitz 2002a; Hausmann and Velasco 2002; Galiani et al. 2003; Stiglitz 2005); and third, those that place the idiosyncracities of Argentine Convertibilidad model at their core (see Calvo 2002; Carrera Interview 2007; Heidrich Interview 2007). Moving beyond economic accounts, this chapter will also examine two further “political” issues of importance—the response of the radical left and their interpretation on the one hand, and the role of political parties and politicians on the other. This chapter is therefore split into five sections before some tentative conclusions are made.

Competing Interpretations in the Literature

Argentine Fiscal Policy and Debt

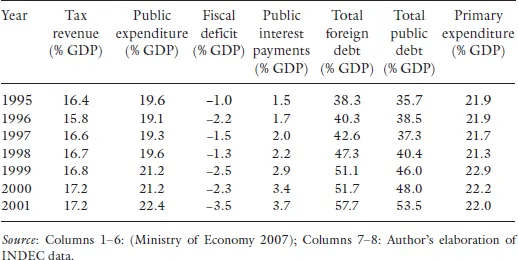

Mussa (2002) and Daseking et al. (2004) emphasize that the crisis was rooted in insufficient fiscal tightening during the 1990s when the economy was growing at a reasonable pace. This, they claim was partly because of the overestimation of potential growth in the 1990s, but mainly due to the actions of the Argentine Federal government. In characterizing those actions, Mussa (2002, 7) describes the state as acting like a “chronic alcoholic—once it starts to imbibe the political pleasures of deficit spending it keeps on going until it reaches the economic equivalent of falling down drunk.” As table 1.1 demonstrates, public expenditure grew as a percentage of GDP throughout the late 1990s and consistently exceeded revenues, leading to a steadily increasing budget deficit—from 1 percent of GDP in 1995 to 3.5 percent by 2001—with the total public debt burden reaching 53.5 percent of GDP by 2001.

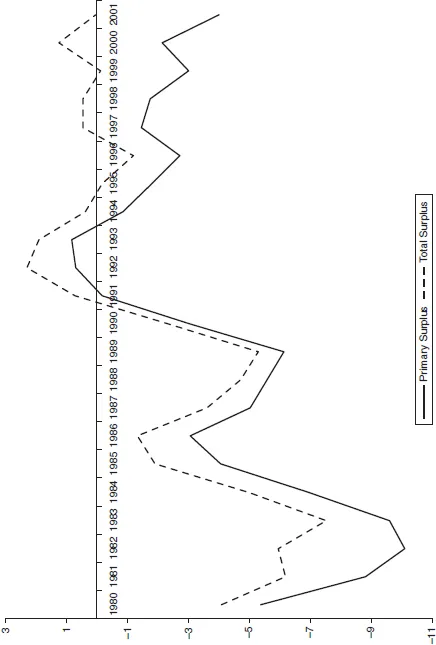

This argument, however, overlooks the fact that (as illustrated in table 1.1) the primary expenditure of the state did not increase as a percentage of GDP from 1993 onward (Heidrich 2001, 1). Furthermore, as figure 1.1 shows, the primary surplus (the excess of government total income over its expenditure not including interest payments on debt) remained above or near zero. However, the overall surplus diverges from this primary surplus throughout the 1990s. This disparity was due to the Argentine state’s increasing external debt burden. What is therefore clear is that its spending before interest payments on debt remained relatively unchanged as a share of GDP. For this reason, Galiani et al. (2003, 120) conclude, “[t]he evolution of public finances was not a big cause for alarm.” What did increase exponentially were the external debt payments, which grew from US$6 billion in 1992 to US$14.5 billion by 1999. This increase was a result of the rise in international interest rates and the swings of country risk, which were largely a function of crises in other emergent economies. Damill et al. (2003, 203) concur with this when they identify higher interest rates (a result of an increase in the country risk premium) as the main factor behind the increase of the fiscal deficit in 1998–2001 (see also Avila Interview, 2007).

Table 1.1 Argentine fiscal accounts 1995–2001

Figure 1.1 Evolution of primary and total surplus as a percentage of GDP 1980–2000.

Source: Author’s elaboration of Ministry of Economy figures, 2007.

Although government primary expenses remained constant as a percentage of GDP, state income declined from 1998 onward for two reasons: first, in the early and mid-1990s there were substantial one-off income streams from the proceeds of privatization. Therefore, when Menem began to run out of industries to privatize, significant revenues ceased to enter the Federal government coffers. Second, in 1995 the minister of economy Domingo Cavallo—reduced the contributions that companies had to make to pension funds from 18 percent of the wage to 8 percent in order to compensate them for the lack of competitiveness, which resulted from the pegged exchange rate (Convertibilidad). This left the social security system financially stretched, and contributed to the deficit rising from 1 to 3 percent of GDP, (and accumulating US$45 billion of debt) between 1995 and 2001 (Heidrich 2002; Galiano et al. 2003: 128). Damill and Frenkel (2007, 117) suggest that this increase in public deficits as a result of pension reform was a major factor in creating structural public fiscal deficits, which were ultimately responsible for the economic roots of the crisis of 2001–2.

This analysis suggests that increasing budget deficits throughout the 1990s were not the result of chronic alcoholism, as the government’s primary expenditure did not significantly change as a percentage of GDP throughout the period. However, domestic policies such as Convertibilidad, and international factors such as external crises and rising market spreads, were responsible for an increasing debt burden that put unsustainable pressure on the public accounts. The picture that emerges is therefore not one of simple continuity with the legacy of a profligate ISI, desarrollista, Peronist past. However, in highlighting the worsening fiscal situation beyond the government’s budget figures, as well as exploring the reasons why a high debt to GDP ratio was particularly problematic for Argentina, Mussa did identify some key trends in Argentine macroeconomics that must be discussed further in order to unearth the reasons behind the crisis. These will be discussed in the next section.

Investor Expectations and Growth

By identifying fiscal imbalances as the reason for the collapse, Mussa and others have highlighted lack of growth as a symptom, rather than a cause, of the crisis itself. Stiglitz suggests that mounting fiscal deficits, and thus an inability to pay its debts, was the result of disappointing growth, rather than an irresponsible Argentine government (Stiglitz 2002b, 69; see also Tresca 2005, 12). Ultimately this led to a drop in confidence in Argentina’s markets, precipitating into a full-blown financial crisis as “hot money” easily flowed out of the country due to an overly liberalized financial system (Tresca 2005, 131).

The question that this critique raises is why did Argentina experience disappointing growth in the 1990s, especially after 1998? According to Stiglitz (2002b), one major factor that accounted for this limited growth was the structure of Argentina’s banking system. Under Carlos Menem’s reforms Argentina had liberalized its financial sector and privatized many of its publicly owned banks. While these larger, foreign-owned banks provided greater security for depositors than small local ones and therefore increased financial stability, they tended not to lend to small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). Stiglitz emphasizes this resulting credit crunch for small business as the reason for Argentina’s lack of growth (Stiglitz 2002b, 69). Hausmann and Velasco’s (2002) analysis also supports this, arguing that the origins of the crisis lie in the acute growth downturn from 1998 onwards. At that time, expectations of future export growth declined sharply, leading to smaller capital inflows. This is especially important given the nature of Argentina’s (mostly foreign-held) debt and therefore its need to generate foreign currency revenue streams in order to service it. This also led to lower domestic investment, which depressed output and had a negative impact on Argentina’s creditworthiness and ability to borrow further in order to continue refinancing existing debt.

Neoliberal restructuring in the 1990s combined with the actions of global capital (from the IMF to international bond markets) during the crisis period are insufficient explanations for the nature of collapse in 2001. The installation of a system of Convertibilidad in 1991 contradicted IMF advice (although that institution would come to endorse the idea later in the decade), representing an idiosyncratic country-level response that was grounded in specific (inflationary) legacies from previous models and strategies of development from its recent history. Once again, in analyzing the causes of the crisis from a simple dichotomy of old and new, a false picture has been drawn. Just like legacies of Argentina’s ISI past cannot be shown to be the cause of 2001–2, neither can the neoliberalism of both the Argentine state and the global political economy.

Expectations also played a further role in the crisis, although not pessimism but rather overly optimistic expectations (Carrera 2002; Galiani et al. 2003). The dynamics of both fiscal accounts and the Real Exchange Rate (RER) (see next section) have to be understood in the light of economic agents’ forecasts about the future path of the economy (see also Chudnovsky 2007, 139). In the 1990s most economic agents (private and public) were making decisions based on an assumption of a permanent income that was higher than sustainable realities would allow. In other words, “after great expectations came hard times” (Heymann Interview 2007).

As figure 1.2 shows, per capita income was above the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) trend (a line of best fit that is able to smooth out the effects of short-term shocks) throughout the 1990s. Alternatively expressed, purchasing power was above the long-term average during this decade. Taken in conjunction with figure 1.3, this shows that during the 1990s investment was buoyant, as can be expected during growth years. However, savings were relatively low for a period of economic expansion (see also consistent current account deficit in table 1.2). Argentina’s economic agents (businesses, individuals, and government agencies) were increasing investment with optimistic views about the economy in the future, but nevertheless reducing their savings. Galiani et. al. (2003) argue that the perception that income would continue to grow validated decisions to get further into debt, as future income would be sufficient to repay/refinance such debt (Heymann Interview 2007). These predictions were proved wrong, and large accumulated dollar liabilities became unserviceable as other factors shook the confidence in, and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction Revisiting the Argentine Crisis a Decade on: Changes and Continuities

- Part I The Political Economy of (Post)Crisis Argentina

- Part II Social Movements and Mass Mobilization before, during, and after ¡Que se vayan todos!

- Part III Cultural and Media Responses to the 2001 Crisis

- Afterword

- Contributors

- Index