![]()

1 HOW THE BACK WORKS

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

The spine is divided into five regions: cervical (neck), thoracic (mid-) and lumbar (lower), with the sacrum and coccyx forming the rudiments of the tail. The spinal column as a whole is made up of 33 individual bones (vertebrae). Each vertebra is numbered to show its position. Cervical vertebra numbers start with ‘C’, thoracic ‘T’, lumbar ‘L’ and sacral ‘S’. So, for example, the second cervical vertebra counting down from the head is C2, and the fourth C4. The numbering system for every section begins at the head, so the last lumbar vertebra is L5. Note also that, until the 1950s, the Thoracic area was commonly called the Dorsal region, so old books or papers which quote them may use ‘D’ instead of the ‘T’ to denote this region. In addition to this, some traditional exercise organisations still use the term ‘Dorsal’ in their teaching.

Key point

Vertebrae are numbered from the head down, with C1 just below the head and C7 between the shoulders.

STRUCTURE OF A TYPICAL VERTEBRA

A typical vertebra (see fig. 1.1) has an anterior (front) and posterior (back) part. The anterior portion consists of a large circular body flattened slightly at its back. This body is attached above and below to a spongy vertebral disc. The posterior portion of the vertebra forms an arch (called a neural or vertebral arch). This has a total of seven processes attached to it.

Figure 1.1 Structure of a typical vertebra

Definition

A process is a projection of bone that juts through the skin to form a small mound or knobble on the skin surface. Examples are found on several bones including vertebrae (spinous process), the radius (styloid process), and temporal bone of the jaw (mastoid process).

At the back of the vertebra is the spinous process, the tip of which can be felt with the fingers (this is made easier if the subject bends forward so that the skin is stretched tight). Jutting out at the sides are two transverse processes.

These form the attachment of muscles and are located approximately two finger widths from the centre line. They are covered by muscle and are thus harder to palpate (palpation is the practice of using one’s hands to examine organs or other parts of the body). However, deep palpation can usually locate the transverse processes on a very lean subject. Just in front of the vertebral body is a hole called the vertebral foramen, which encloses the spinal canal. At the angle between the spinous process and transverse process is a shallow cup called the articular process, and there are four of these, two on each side, one above (superior) and one below (inferior). Each articular process is cup shaped and connects with a similar cup of the vertebra above and below to form a small flat joint on each side of the vertebra called a facet joint (also known as an apophyseal joint). The point at which the neural arch attaches to the vertebral body is called the pedicle and the point of attachment to the spinous process is called the lamina.

Definition

The spinal canal is the space in the vertebrae, enclosed by the vertebral foramen, through which the spinal cord passes.

Clinical note

In a operation called a Laminectomy a small piece of bone along the lamina is removed to provide more space around the notes. The operation is performed in cases of disc prolapse (slipped disc) and spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal). Laminectomy is a microsurgery procedure and often some ligament and other tissue will be removed at the same time.

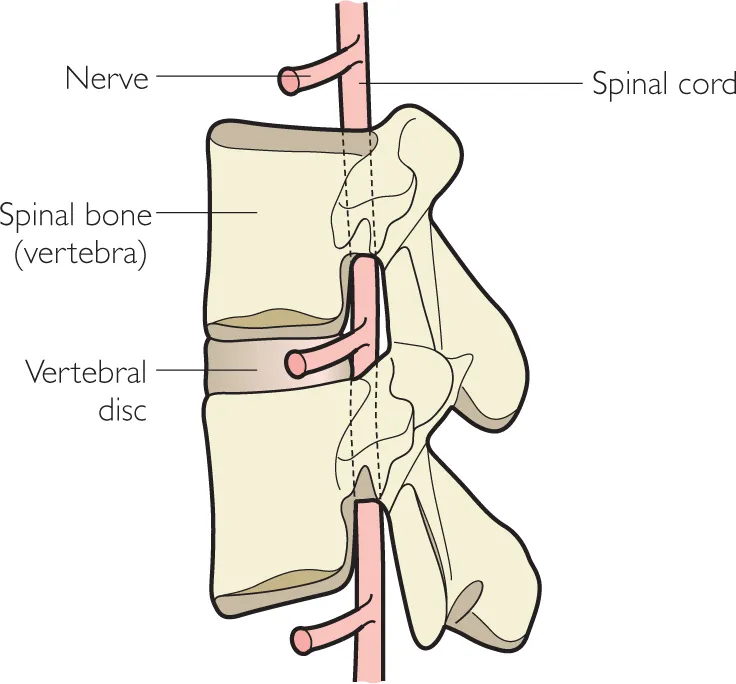

Each pair of spinal bones together forms a single unit called a spinal segment (see fig. 1.2). As we have seen there are three main joints to each Transverse vertebra: the spinal disc in the centre and a small facet process joint at each side. The disc is fibrous, while the facet joints contain fluid. Vertebral We will foramen see in chapter 2 how these joints can be injured or affected by medical conditions.

Figure 1.2 Spinal segment

Definition

A synovial joint is the most common movable joint in the human body. It consists of two bone ends covered by cartilage (hyaline cartilage). The joint is contained within a fibrous bag called the joint capsule, which is lined by a synovial membrane. The joint is lubricated by synovial fluid.

REGIONAL DIFFERENCES

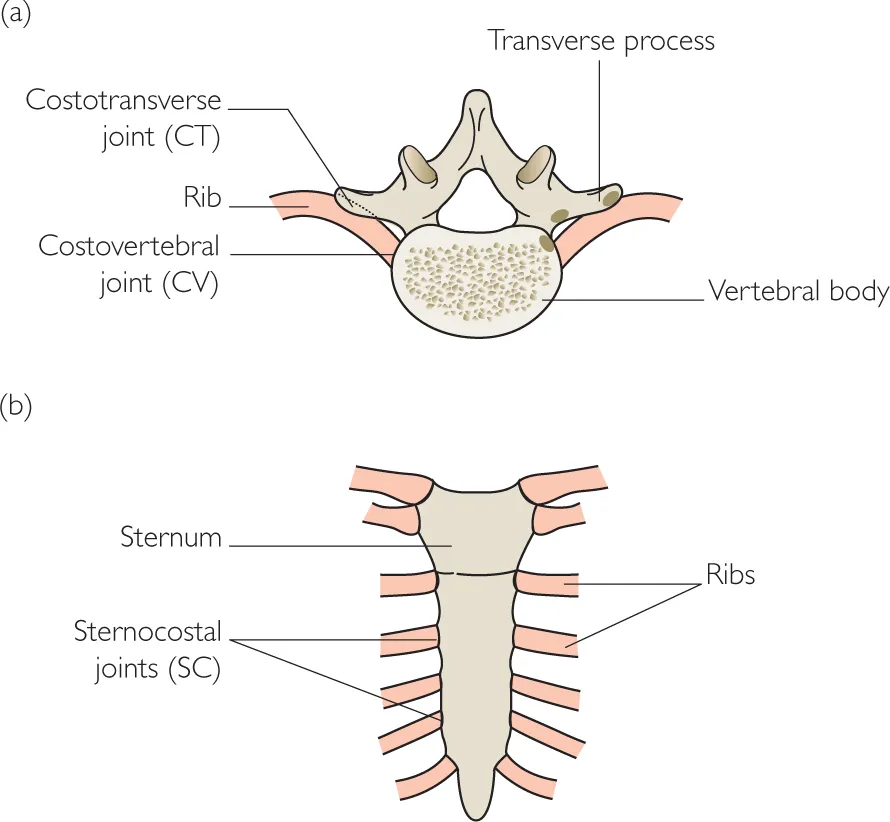

Figure 1.3 shows the differences in structure of typical vertebrae from each spinal region. The cervical vertebra has a small hole at each side called the transverse foramen for the passage of the vertebral arteries through the neck into the brain. The thoracic vertebrae have small joints for the attachment of the ribs (see fig. 1.4). The lumbar vertebrae are large, strong bones covered with powerful muscles. They bear the whole weight of the trunk above them, hence the slightly stubby appearance of their spinous and transverse processes.

Figure 1.3 Differences in structure between typical vertebrae in each spinal region

Figure 1.4 Joints between the ribs and thoracic spine

CERVICAL REGION

The cervical region is subdivided into two functional parts. The upper portion directly below the head is called the sub-occipital region (the occiput being the lower back portion of the skull). The C1 and C2 bones make up this region and these two bones are intimately connected with skull movements – especially nodding actions. The lower portion of the neck is called the lower cervical region and takes in the bones C3 to C7. This region is more involved with twisting (rotation) and side bending (lateral flexion) actions.

Definition

Flexion refers to the action of bending or being in a bent position.

As mentioned above, one of the unique features of the cervical vertebrae is the presence of the vertebral arteries, which pass through the vertebral foramina within the transverse processes. Because the first cervical vertebra (C1) does not have a transverse process, these arteries travel behind the arch of the vertebra, and in 7.5 per cent of people the arteries also do so in C7. The vertebral arteries supply blood to the rear part of the brain. Damage to the arteries can occur during a neck injury, and they can be compressed or restricted in chronic neck conditions and in cases of atherosclerosis.

Definition

Atherosclerosis is a thickening or hardening of an artery wall due to the build up of fatty plaques.

Reduction of the blood flow through the arteries to the brain is called vertebrobasilar insufficiency or VBI (also known as vertebral artery insufficiency). One of the most common mechanical causes of this condition is prolonged neck extension over a period of some minutes, which can in extreme cases lead to a stroke.

THORACIC REGION

In the chest region the thoracic vertebrae are attached to the ribs by two joints: the costovertebral (CV) joint between vertebral body and the rib, and the costotransverse (CT) joint between the transverse process at the side of the vertebra and the rib angle, where the rib curves to form the drum of the chest (see fig. 1.4). When looking at someone’s back, the spinous processes are in the middle forming a straight column of bumps. The CV joint is about two finger breadths to the side lying in the furrow of the back (paraspinal gutter). The CT joint is about 3 finger breadths to the side, covered by the large erector spinae muscles.

Key point

In the thoracic spine, the spinous process is in the centre of the back, the costovertebral joint slightly out to the side, and the costotransverse joint further out still.

LUMBAR REGION

Movement of the lumbar vertebrae is intimately linked to that of the pelvis, as well as the upper spine. The upper portion of the lumbar spine (L1 and L2) moves with the thoracic spine, especially during shoulder blade and ribcage movements. The lower lumbar vertebrae (L3, L4 and L5) move closely with the pelvis, and this combined region is often referred to as the lumbo-pelvis.

THE SACRUM AND PELVIS

At the base of the lumbar spine is the pelvis. This is ring shaped with two large flat bones (iliac bones) on each side. These attach at the front through the pubis to form the pubic symphysis and at the back to the sacrum, which forms a keystone between the two. The sacrum is a triangular shaped bone, which together with the thin pointed coccyx forms the remnants of our tail. The sacrum attaches to the iliac bones via the sacroiliac joint or SIJ.

Key point

The sacroiliac joint joins the sacrum to the pelvis. It is often painful during pregnancy and following childbirth.

These regions are important as there is significant risk of injury, especially during pregnancy and childbirth. The SIJ and pubic symphysis are each filled with fibrous material and normally give little movement. During childbirth, however, the fibrous material softens and the joint moves to allow the pelvis to expand. This motion can inflame the joints and lead to changes in their alignment. The coccyx also becomes more mobile in this period and can cause problems. The coccyx is also vulnerable to damage if someone falls backwards onto a hard floor – lean people are particularly at risk from this kind of injury.

SPINAL CURVES

Although the spinal vertebrae stand one on top of each other, the column they make is not straight. Rather, the spine forms an ‘S’ curve. There are two inward curves in the lower back and neck, while the thoracic spine curves gently outwards. The inner curves are called the lumbar lordosis and cervical lordosis, the outward curve the thoracic kyphosis. These curves are not present at birth, but begin to develop in early childhood.

Definition

An inward (posteriorly concave) curve to the spine is called a lordosis, an outward (posteriorly convex) curve a kyphosis.

In the early years of life, a baby’s spine is rounded, and we call this rounded shape the ‘primary spinal curve’. As the baby starts to lie on its front and lift its head up, the neck curve...