![]()

ONE

The Corporation as an Invisible Friend

Wherein we first learn that our captains of industry, finance, retail, and everything else are irresponsible hypocrites.

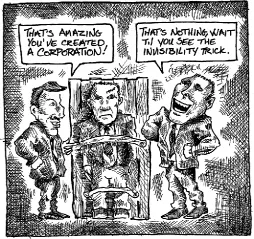

Sometimes when children are young they make certain they have companions by inventing friends. They talk and play with them as if they really exist. A girl might ape her parents and invite them to join her and her invisible friend Kim to take afternoon tea. The amused parents will nod gravely when they are introduced to Kim and may help set a place at the table for the invisible visitor. But the parents will stop the play-acting when their child tries to blame Kim for a broken plate. They are likely to tell their flesh and blood daughter, “Now, stop that nonsense. You broke that plate. You clean it up. Let that be a lesson to you to be more careful in the future.”

Conrad Black has an invisible friend. So does Lord Thomson of Fleet, and so do Wallace and Harrison McCain, Kenneth Irving, Paul Desmarais, Frank Stronach, Galen Weston—as do all other captains of Canadian industry, finance, retail, and everything else. But, unlike our little kid, they are not asked to shoulder the responsibility for any havoc they may cause. They are allowed to blame their “Kim.” They are allowed to hide behind their invisible friends. Conrad Black’s invisible friend is called Hollinger Inc. Lord Thomson’s invisible friend is known as Thomson Corp. One McCain’s playmate is McCain Foods, the other’s is Maple Leaf Foods. Kenneth Irving’s is Irving Co. Paul Desmarais hid behind Power Corporation of Canada for years, as now do his sons Paul Jr. and André. Magna International is Frank Stronach’s greatest pal, and Galen Weston’s are George Weston and Loblaws Companies Ltd.

These invisible friends are corporations. We “hear” corporations talk. They “tell” us, “We are good corporate citizens.” They say, “People are our most important product” and “We do it all for you.” In turn we speak about them as if they have a real existence, as if they were living, tangible beings. It is more common for workers in a dispute with their employer to say “the company is unfair” than “the boss is nasty.” This is so because, for many people, there is no visible human boss to be angry with but only an invisible employer—a corporation. In short, it is a commonplace to acknowledge the reality and existence of corporations and their significance to our lives.

And yet . . . corporations are constructs of law; they are not natural phenomena. No one has ever seen a corporation, smelled a corporation, touched a corporation, lifted a corporation, or made love to a corporation. Conrad Black’s best friend is just as invisible and, in human terms, no more real than Kim, our inventive kid’s creation. But in reality the invention of Kim is a mere psychological and passing stage in a child’s life, whereas corporations are the primary, permanent, and very concrete tools that wealth-owners use to satisfy their never-ending drive to accumulate more riches and power at the expense of the rest of us, the majority.

The Essential Characteristics of the Invisible Friend: The Corporation-for-Profit

One of the more astonishing things about this legal creation (and there are many) is that there are virtually no legal barriers to hurdle for any individual who wants to form a corporation. Individuals need not give any reason to anyone as to why they want to form a corporation. Nor does an individual need any money, over and beyond the wherewithal to pay a derisory registration fee, to form a corporation. Every sane, non-bankrupt adult has the right to form a corporation by meeting a few minor procedural requirements to the satisfaction of a government bureaucracy. Evidently, the law is eager to help us to create corporations. Also, the law’s largesse does not end once it has helped a real, live, human being establish a corporation. When a business takes on a corporate form, a number of truly wondrous things happen.

First, upon registration—that is, upon birth—the corporation is instantly mature. There is no childhood or discombobulating adolescence to go through, phases through which we, mere mortals, have to suffer. Until we humans become adults, we are not trusted with the full legal rights and privileges, nor are we encumbered by the legal obligations, of social and political citizenship. Unlike us mere humans, a corporation does not have to go through a maturing, proving-itself-worthy period. From the moment it is registered—and, remember, that is no trick at all—it has all the legal capacities it is ever going to have.

This brings us to the second facet of its instant attributes. In some important ways, the legal capacities of corporations are greater than those of human beings. A corporation can buy, sell, lease, and own property, just like any adult Canadian. But, unlike us, a corporation can do so for ever. It has perpetual life; it does not age. To die, it must be killed (say, by a forced liquidation), eaten by another predator (say, by a successful takeover bidder), or commit suicide (say, by a voluntary liquidation). Being born fully mature, a corporation can instantly give birth to another corporation, or even thousands of others, by registering new entities as soon as it begins to “breathe.” In turn these offspring can do the same at the very instant of their birth, that is, upon being registered. There is no pesky gestation period, nor are there any natural/biological limits on reproduction. Real live people imaginatively use this power to create family members at will to obscure corporate doings and to manipulate taxation and other laws.

This creative process is carried out in conjunction with the third characteristic of the corporation, one that is just as fantastical as the first two. Given that, upon birth, the corporation instantly acquires a whole range of capacities to engage in legal transactions—in lawyers’ terms, it is endowed with some form of legal personality—what does it mean to say that something or someone has a legal personality? And what is the importance of noting that a corporation has it?

Each nation-state endows its citizens with a set of rights and duties that create a legal envelope within which the people of that nation-state can conduct themselves. Every political entity, then, bestows on its citizens a political and economic autonomy reflecting the scope of sovereignty of the human members of that polity. The content of this sphere of freedom of decision-making and action is termed the legal personality—as opposed to the psychological personality or the biological makeup—of a nation’s citizens. In Canada we pride ourselves on having given ourselves a great deal of scope to make our own decisions; and, therefore, we boast that freedom reigns in Canada. We believe that this country grants its citizens the respect they should be accorded as sentient human beings. As it turns out, we accord very much the same level of respect to non-human beings, to non-sentient beings. Canadian law grants corporations, the invisible friends of our various captains of industry and everything else, the same kind of legal personality that it grants to you and me. Section 15 of the Canada Business Corporations Act unequivocally states, “A corporation has the capacity and . . . the rights, powers and privileges of a natural person.” It could not be plainer: the law treats corporations as if they were real people. This gives corporations unexpected, indeed extraordinary, attributes.

Of course, there are some human things that a corporation obviously cannot do despite having been granted a form of personhood. A corporation, being an abstraction, obviously cannot think or have a belief, and therefore it cannot vote as if it were a flesh and blood citizen. Even this logic, though, is coming under attack. In Sydney, Australia, corporations are permitted to vote in municipal elections if they own, lease, or occupy rateable property; but that is the exception to the rule. Still, it turns out that the mere lack of human attributes does not always disqualify a corporation from claiming rights that we think of as rights that belong to human beings because, well, they are human rights in the sense of being rights associated with social relations between living persons.

A corporation legally can engage in speech, base claims on human beings’ religious or political beliefs, or even claim protection for its need for privacy, as if it were a man or woman who craves private space for intimate thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. All scientific logic, it seems, is thrown out the window when it comes to corporations. We are to apply corporate law logic, and that logic is weird. To enable them to ward off the impact of some government regulation they do not like, corporate persons frequently claim to have what an ordinary person might think of as peculiarly human moral and political attributes. In addition—and most importantly—the grant of a legal personality allows corporations to own property, just as you and I do.

This right draws attention to the fourth major characteristic of this particular invisible friend: it has something lawyers call limited liability. The new legal person, the corporation, owns the property invested in it and borrowed by it to carry on business. It is this feature that enables it to buy, sell, lease, assign, or mortgage property and things, just as any free, adult Canadian can. This ability makes the corporation truly separate and distinct from its investors. The separate legal personality and its other capacities come as part of a package that includes limited liability—a truly stunning attribute.

For example, let’s say a certain investor—we’ll call her Mary Worth—makes a contribution of capital to a corporation on the understanding that she will share in the profits (if any) of the business carried on by the corporation. The value of her entitlement is related to the proportion that her contribution bears to the total of such contributions. As evidence of that interest, the corporation issues Mary a certificate describing the extent of her interest. This is a share certificate and Mary, the investor, is now called a shareholder. A shareholder can sell the certificate, the piece of paper. There is a market that attaches values to these pieces of paper—the stock or share market. The shareholders, therefore, can be said to have legal title to the value of that paper. But the investor no longer has legal title to the capital she contributed to the corporation. The legal owner of that capital is now the corporation.

No longer being the legal owner of the invested capital, and not being the legal person who enters into the corporation’s business transactions, the investor/shareholder is not held personally responsible for any obligations incurred by the corporation. The only thing Mary Worth has on the line is her initial investment, which might be lost by the corporation. Her personal wealth is not available to anyone to whom the corporation owes money, even if the corporation cannot meet obligations that it incurred because of its efforts to return profits to Mary Worth as an investor/shareholder. This, of course, is what makes it attractive for owners of disposable wealth to invest in incorporated businesses as opposed to other kinds of businesses. Investors, who pride themselves on being called risk-takers, like to shift the risks they have had created on their behalf to others. This is what is called limited liability: the cat’s out of the bag.

The very logic of the legal corporation, then, requires us to throw out our usual way of speaking and thinking about such things. Everything is upside down. What is apparent is that when people say a corporation has limited liability, they mean the opposite. The corporation’s liability, like yours and mine, is only limited by its physical ability (that is, by the extent of its assets) to honour that liability. Its legal obligation, like yours and mine, is not limited. It is the investor/shareholder whose liability is limited. What is carefully hidden by saying that a corporation has limited liability—that is, hidden by the perverse use of language—is that it is people who, if they were not shaded from legal view by the veil of corporate personality, have limited liability. It is not Hollinger Inc., Thomson Corp., McCain Foods, Maple Leaf Foods, Irving Co., Power Corporation, Magna International, and George Weston and Loblaws that have limited liability, but it is Conrad Black, Lord Thomson, the McCain brothers, Kenneth Irving, the Desmarais brothers, Frank Stronach, and Galen Weston who are so blessed by corporate law. They are only responsible to the extent of their actual investment for the obligations incurred by their corporation as it pursued wealth for their benefit. The magic of corporate law has made them less responsible than you and I. We are legally responsible for all the harm we cause and for all the debts we have incurred in our pursuit of profits.

It is, of course, the same “hidden behind the veil” corporate captains of industry, finance, retail, and everything else, and their mouthpieces, who continuously urge the rest of us, unincorporated human beings, to stand on our own two feet, to take responsibility for our own actions. We are told that we should not rely on artificial protections and, especially, that we should not accept handouts from governments just to shield us from the operation of the market. We should participate in market activities and take our lumps, as sovereign beings are expected to do.

This clamour for self-reliance, for taking responsibility for one’s actions, orchestrated by the leaders of our corporate world, provides us with a new definition of “chutzpah,” the Yiddish word for cheekiness or unmitigated gall. Chutzpah is often defined as the characteristic of a man who, having been convicted for killing his parents, throws himself upon the mercy of the court on the grounds that he is now an orphan. This is much like the rich people who, having used their corporate vehicles to further enrich themselves, doing harm to others and leaving unpaid debts in the process, now throw up their hands and ask their victims disingenuously, “Why did you not take steps to protect yourself from our corporation’s acts? Tough luck; you only have yourself to blame.”

The Story So Far

Everyone knows that the corporation Hollinger Inc. does the bidding of Conrad Black. Everyone knows it does so because Conrad Black is both a major investor and decision-maker in the corporation. But when the pressure is on, should there ever come a moment when Hollinger has inflicted harm on others that it cannot afford to redress or if it has incurred debts that it cannot afford to repay, Conrad Black will be able to rely on the corporate law that has made Hollinger legally speaking—not functionally, not morally, but legally—a person totally distinct from Conrad Black. Legal logic—and no other—will permit Black to say that, in a society based on individual responsibility, he cannot be made responsible for the acts of a truly discrete, separate person, Hollinger, the corporation.

This is particularly offensive, for no matter how often lawyers repeat the mantra that a corporation is a legal person, just like you and me and Conrad Black, it is not. It does not have flesh and blood or a mind like you and me and Conrad Black. It cannot act; it cannot think. It can only do so when some real people, with flesh and blood and a mind, do so on its behalf. How, then, can a corporation be said to be a person in its own right, making it appropriate to attach responsibilities to it and to no one else? To counter this dangerous line of argumentation and questioning, (dangerous to the legitimacy of the corporation), corporate law has had to concoct yet other myths.

Some of the corporation’s senior managers—those designated as directors, officers, or executives—are treated as if they were the corporation. The thoughts and acts of these flesh and blood functionaries are deemed to be the thoughts and acts of the corporation. They are the acting will and mind of the corporation. This condition papers over the obvious inability of an inanimate being to exercise a will and to do acts. By identifying the corporate person as being the same as the real persons who are appointed to act on its behalf, those concerned find it possible to pretend that a corporation can think and act. But this is only a pretence, and it causes problems in the real world. Law has to engage in some more contortions to avert the inevitable difficulties that ensue. As some more weird corporate law kicks in, new and unappetizing outcomes emerge.

As the thoughts and acts of the very real human beings who are the directors and officers of the corporation are treated as if they were the thoughts and acts of the corporation, they are—legally speaking only, of course—not the thoughts and acts of the directors and officers as people. It follows that the corporation, and not the directors and officers, should be held legally responsible for those thoughts and acts. As a consequence, investors in the corporation are not the only ones blessed with limited liability for risks created by their wealth-seeking activities through the corporation. Directors and officers and executives have a form of limited responsibility as well.

This embarrassing state of the law is based on the mythology that the corporation is a separate person, an artificiality that we are all expected to condone because of the market conveniences it bestows. The state of the law is embarrassing, because it contradicts our elites’ frequently intoned claims of belief in the social, political, and economic value of the...