CHAPTER 1

Getting Started

FIRST—LOOK AT YOUR CONTEXT

UNDERSTANDING YOUR CONTEXT IS KEY STARTING DOWN THE PATH of IPE. In order to share the Toronto Model, we must first describe our context and our structures, and the types of programs, learners, and clinical partners that characterize health professional education at Toronto. More broadly the rise of IPE in Canada was stimulated by a series of key federal and provincial (or state) initiatives that provided the impetus for early adopters. In this chapter we share how we began.

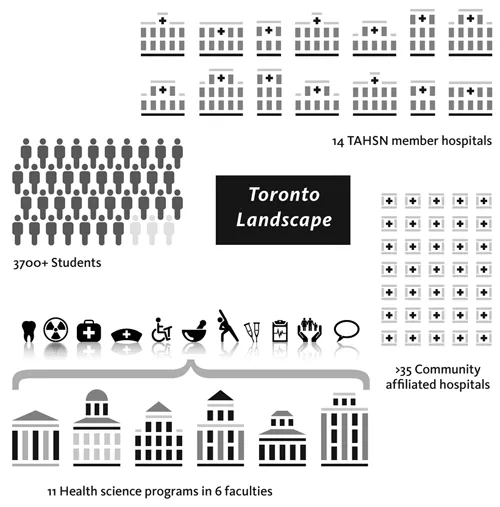

WHAT DOES THE TORONTO LANDSCAPE LOOK LIKE?

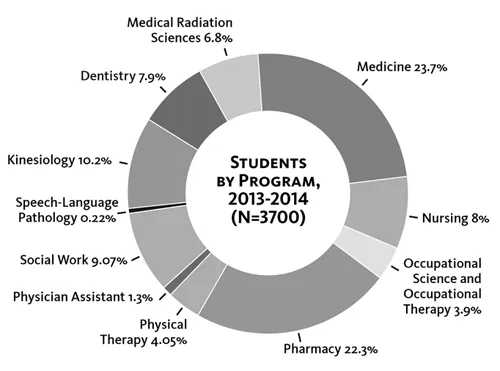

The University of Toronto (U of T) is a large public research–intensive university with 80,000 plus students and 11,500 faculty. We have a large medical program with nearly 1,000 undergraduate students, 3,000 graduate students, 2,000 residents, and 3,000 postdoctoral and MD clinical fellows1 and partner with dozens of affiliated hospitals (teaching and community hospitals). In Ontario alone, one third of all family doctors have received training at U of T, and nationwide, one quarter of all medical specialists did all or some of their training here.2 Medical education therefore features prominently in the U of T story. The Faculty of Medicine also includes five distinct health science programs: medical radiation science, occupational science and occupational therapy, physical therapy, physician assistant, and speech-language pathology. The faculties of dentistry, kinesiology and physical education, nursing, pharmacy, and social work are by comparison much smaller than medicine. Nursing, for instance, is about a tenth the size of medicine overall at Toronto (see Figure 3).

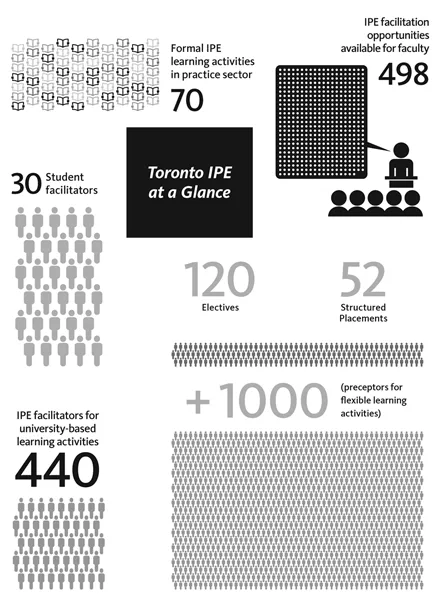

Figure 3—The elements of IPE at Toronto

http://www.tahsn.ca

In addition to size, the nature of the academic health science centre at U of T is unique. The Toronto Academic Health Science Network (TAHSN) is characterized by a strongly integrated set of linkages that functionally connect leaders in the hospitals with their academic partners at the university. The university doesn’t own or run the hospitals, as happens in some academic health science centres around the world. The U of T and the teaching hospitals form a consortium that is based on health professional education and research. This mix of strong sovereign identities among many partners, along with a cohesive purpose around education and research, is what makes TAHSN complex to maneuver and rich in potential. Every physician is appointed to the university, as are many hundreds of other health professionals. These appointments may be paid; many are unpaid. Appointments may come with teaching expectations or clinical supervision and mentorship, whereas others are largely research-focused.

WHAT ARE OUR STUDENTS LIKE?

Ten of the eleven health science programs at U of T (with the exception of kinesiology and physical education) are second-entry undergraduate or graduate programs, so students have undertaken university studies prior to entering their health science program. Typically the students have completed an undergraduate degree and, for some, a master’s degree (nursing, medicine, pharmacy, and dentistry fit this model). Other programs (such as rehabilitation sciences and social work) are offered only at the graduate level. What this means is that students tend to be roughly the same age—mid- to late twenties on average. The relative maturity of U of T students, we believe, becomes significant when students share learning and team activities.

Figure 4—Breakdown of Students in U of T IPE Curriculum

THE IPE PROGRAM

The scale of interprofessional education and care (IPE/C) in Toronto is remarkable. There are approximately 3,700 learners engaging in over 120 IPE learning activities offered across eleven professional programs in partnership with fourteen fully affiliated teaching hospitals and approximately thirty-five community hospital affiliated sites. Each year, these learning activities are supported by 620 mentors made up of student facilitators (30), IPE facilitators for practice-sector learning activities (150), and IPE facilitators for university-based learning activities (440) (see Figure 4).

At Toronto, IPE/C is not marginal—it is mainstream. There are teaching, practice, and leadership awards for faculty and students; a student association and a student-run clinic; faculty positions; teacher and clinician education; and leadership development programs. Students learn about, with, and from each other, and they learn how to work together in teams. They then get to practice in both academic and clinical settings.

For the most part, the IPE curriculum is an enhancement of the uni-professional learning (i.e., learning within a single profession) that stu dents undertake in each of their accredited programs. We are fully aware that it is not enough to simply put learners from different disciplines in the same class. We start from the philosophy that team learning needs to be an active component of the curriculum in order for the learning to be directed to improved team outcomes.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR IPE IN TORONTO

EARLY EFFORTS

Health professional students learning together and practicing in teams is not a new idea. Over the course of the twentieth century, various experimental and model programs introduced co-learning and combined learning in which students from different health professional programs may sit in lecture theatres together learning anatomy or ethics. Students often learn in multidisciplinary groups to solve problem-based learning exercises, or they may be placed in teams, such as mental health teams or pain teams, as part of their clinical training. None of those approaches equates with IPE. Interprofessional education is something quite different. It directly addresses the issue of professional culture and identity and looks for ways to assist learners to grow and mature as health professionals (nurses, doctors, pharmacists, and so forth), as well as learning about what their colleagues do and know. It also helps them to develop the skills and capacities to work together to improve care.

Figure 5—IPE annual participation data

Learning how to collaborate with colleagues is not the same as learning with colleagues. If we want practice to be team based, we have to do more than put people into teams. We have to teach people how to collaborate. Importantly, IPE needs to address tenacious issues such as culture, trad ition, and power. This is not a task for the faint-hearted.

By the 1980s, in several sites around the world, most notably in the United Kingdom, the idea of interprofessional care had begun to take hold. Studies published in the groundbreaking Journal of Interprofessional Care began to pique the interest of Canadian health care leaders. Emeritus Dean of Nursing Dorothy Pringle at the U of T recalls that in the mid-1990s, a Council of Health Sciences Deans was created at the suggestion of the provost, which she subsequently chaired. Pringle remembers that although there was a growing number of initiatives that provided IPE learning opportunities for students at U of T—such as the Year 1 session that brought all first-year students together to attend a panel of patients and clinicians each year—the one thing that everyone felt was missing was practice-based experience in team work. The Council didn’t want IPE to be merely a classroom exercise and hit upon the idea that they would use the recently created medical academies, which were academic footholds in the teaching hospitals, as structures around which to build IPE. The ambitious goal of the time was to offer a handful of students from the different programs an opportunity to work with a strong team in a position to model collaborative practice.

Money was found to hire four interprofessional practice coordinators in each of the medical academies to look for great teams suitable for student placement, to work with and across the different faculty programs to figure out what the curriculum and timetable issues were, and then to work with students during their placements. The whole thing was an experiment in seeing what could be done to bridge the faculties and the hospitals and to support the students in the practice placement. These coordinators reported to the Council of Health Sciences Deans and laid the groundwork for the more ambitious scheme that would follow when the timing was right.

In 2000, when the American Institute of Medicine released To Err Is Human,3 the report gave the Canadian interprofessional movement a big push forward. The public revelation that medical errors were killing thousands of patients every year galvanised support for change—not only in the United States but also in Canada.

POLICY DRIVERS

In Canada, the government agenda was also influenced by the 2002 release of Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada. In this report, lead author Roy Romanow, a former provincial premier, recommended an integrated approach to preparing health care teams: “If health care professionals are expected to work in teams … their education must prepare them to do so.” The Romanow Report made forty-seven recommendations for sweeping changes. Recommendation #17 began: “The Health Council of Canada should review existing education and training programs and provide recommendations to the provinces and territories on more integrated education programs for preparing health care providers.”4

The Romanow Report led to a series of national and provincial initiatives to support team care, and some U of T leaders were ready to be part of the first charge. One of the great champions of IPE was the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (Toronto Rehab; now part of University Health Network). The teaching hospital hired Lynne Sinclair, who was in a leadership role at U of T’s Department of Physical Therapy, to start up the facility’s IPE program and create a sustainable interprofessional learning environment. Sinclair credits the chief nurse executive at the time, Karima Velji, with the vision to appoint her to the city’s first IPE job in the practice setting. Sinclair says Velji just “got it” right from the beginning. The stars were aligning for IPE/C in the province of Ontario. Collaborative health care delivery had become a political mandate. A handful of champions had by now assembled at U of T and were eager to catch the political wave and move the IPE agenda forward.

HOW IT BEGAN

A key early driver at U of T was the establishment of the Office of Interprofessional Education (Office of IPE) under the leadership of founding Director Ivy Oandasan, a family physician. Established in 2005, it would eventually evolve into the Centre for Interprofessional Education (Centre for IPE), described below, in 2009. But in these early years, the foundational work of Oandasan and the Office of IPE concentrated, for the first time, IPE/C efforts in one conceptual and also physical home. Between 2005 and 2009, the Office of IPE played a leading role attaining grants totaling over $17 million by leveraging faculty and health professionals across the university and teaching hospitals. This was enabled by the emergence of both a national and provincial strategy to support team practice in health care and funding incentives in the field. In 2005, Joshua Tepper, a family physician, became Canada’s first assistant deputy minister with a health human resources portfolio. To address the shortage of health care workers in Ontario, he believed the province needed more than just additional health professionals. “I knew we had to do things differently,” he says. “Health care providers simply had to work differently.”

Tepper was a proponent of IPE long before the acronym was coined. His training and early clinical practice in rural, remote settings taught him that each health profession offers unique insights. “The person who taught me how to put on casting was an X-ray technician in Red Lake, Ontario. Her name was Tutsi,” he recalls. “The person who taught me how to start IVs was a nurse in Bella Bella, British Columbia. In the U.S., I was taught by physician assistants. Many of my first deliveries were with a midwife in Africa.” While Tepper learned to appreciate the knowledge and skills of his colleagues, he doesn’t confuse this collegiality with interprofessional care. He explains, “Many people will say, Oh, I work on a team because there’s a nurse there and a physiotherapist here, and a social worker and doctor over there.’ Just because they’re all on the same ward doesn’t mean you have a team. What you have is a bunch of individuals working in parallel.”

The public wasn’t as enamored with interprofessionalism as Tepper. “People said the government wanted interprofessional care because it was the cheap way,” he recalls. “That’s a myth! It is far from a cheap way; in fact, it is probably more expensive. It took time for people to see that this way of delivering care would improve quality because it allows you to leverage a variety of skill sets.”

Tepper was eventually successful in pushing the IPE/C and quality care agenda in Ontario. IPE proponents at U of T were quick to apply for government dollars at both provincial and national levels, and an opportunity arose in 2005 when Health Canada, the federal government’s health department, announced a competition for innovative, potentially transformative projects in IPE/C. Catharine Whiteside, then the Faculty of Medicine’s associate dean of Graduate and Inter-faculty Affairs, and Brian Hodges, the second director of the Wilson Centre, were part of the group who came up with a plan for U of T, which at the time had little experience applying for large-scale platform funding for IPE/C. “We stayed up late one night in Catharine’s office submitting the final propo...