![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Forging Diaspora in the Midst of Empire

The Tuskegee-Cuba Connection

In November 1901, a group of students arrived at Tuskegee Institute from Cuba with a letter of introduction from Juan Gualberto Gómez, the famous Afro-Cuban patriot. Gómez had exhibited his nationalist credentials during his fierce battle for Cuban sovereignty against the U.S.-imposed Platt Amendment in the Cuban Constituent Assembly. Now, only a few months later, he sent four students to Tuskegee, the famous school for African Americans in the nation that had successfully thwarted Cuban independence. Among these pupils was his son, Juan Eusebio. “I hereby take the liberty of recommending to you Lorenzo del Rey Jr. the bearer of this letter,” the elder Gómez wrote in English to the school's principal, Booker T. Washington, “who wishes to be admitted in the Institute whose Directorship you fill with so much tact and credit. . . . I ask of you, as you are so kind always, to admit him.” While Gómez revealed that del Rey was unable to pay for his education, he insisted that the student was “sufficiently advanced in machinery, and [would] work while there so as to be less onerous to the Institute.” Gómez hoped that the school would “make a man of him,” as well as the other students who arrived with his son, including Ramón Abreu, Nicolás Edreira, and Romualdo Cárdenas. The long-time advocate for Afro-Cuban education thanked Washington in advance for accepting the students and promised to “create an Association here whose purpose will be to send every year a number of students to Tuskegee, where tuition will be paid by said Association.” Gómez concluded his letter by expressing his admiration for Washington's “love for the advancement of your brothers.”1

Gomez's letter to Washington highlights the Tuskegee Institute's role in the formation of Afro-diasporic linkages at the turn of the twentieth century. It also provides revealing evidence of two men who have usually not been viewed by historians as diasporic subjects beyond their national contexts. Interpreting this letter requires one to go beyond existing portrayals of both of these wellknown figures: Gómez — the Afro-Cuban nationalist loyal to Cuba Libre — Free Cuba; Washington — the African American accommodationist acquiescent to Jim Crow segregation. In the midst of imperial transitions in Cuba and the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, both became key players in the formation of cross-national relationships between Afro-Cubans and African Americans. The fact that Gómez, an iconic Cuban nationalist figure, sent his son to a black American school in the U.S. South illustrates the material benefits that relationships with African Americans could provide for Afro-Cubans even at the precise moment of Cuban national formation. Hundreds of other Afro-Cuban parents and guardians did the same, not as an act of diasporic political solidarity, but in the hope of obtaining some sort of advanced schooling for their sons and daughters due to the absence of viable options in their homeland. Thus, Tuskegee became a site of diasporization not only through Washington's efforts, but more importantly through the agency of people of African descent who were inspired by his message of “up from slavery.” In this way, Afro-diasporic subjects in Cuba and other parts of the diaspora gave the Tuskegee phenomenon a meaning that transcended the racial politics of the United States in the Jim Crow era.2

Aspiring Afro-Cubans like those who were advised or assisted by Gómez found Tuskegee to be an attractive school for their teenage sons, and occasionally their daughters, because of its growing international reputation. In an era when racial segregation was becoming the governing principle of education in the southern United States, Tuskegee, and its predecessor Hampton Institute, championed what became known as the “Hampton-Tuskegee Idea” of industrial education for people of African descent. Tuskegee became the preeminent model of industrial training. Founded by ex-slave and Hampton graduate Booker T. Washington in rural Alabama in 1881, the institute grew rapidly and superseded Hampton as the most prominent and best-endowed school for African Americans. Tuskegee quickly developed a national and international stature, attracting thousands of students from across the United States and other countries, including hundreds of Afro-diasporic students from the African continent, the Caribbean islands, and Central and South America. As this chapter shows, Afro-descended students from Cuba and Puerto Rico were among the first students from abroad to enroll at Washington's school, due to the islands' geographic proximity to the United States and their centrality to the plans of U.S. imperial expansion.3

In many ways, Afro-Cuban encounters with Tuskegee mirrored the larger power relations embedded in the U.S.-Cuban imperial encounter at the turn of

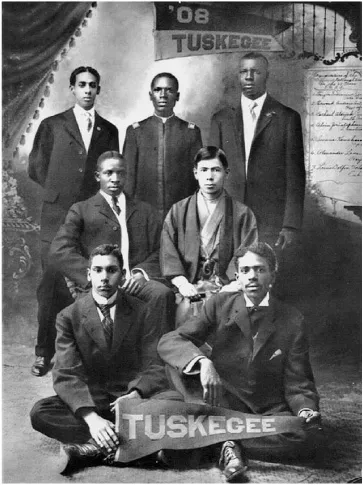

Representatives of the different nationalities in the 1908 class of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. Clockwise from top left: Saturnino Sierra Feijoo, Puerto Rico; Edward Andrens Anthony, Togo; Bethel Aldrick Posey, San Andrés Island, Colombia; Iwane Kawahara, Japan; Alexandre Lavard, Haiti; Luís Delfín Valdés, Cuba; and Alvin Joristophones Nealy, United States.

the twentieth century. Washington, like many African Americans at the time, tried to harmonize his loyalty to the United States with an identification with the worldwide colored race. His attempt to apply his model of racial uplift to Afro-descended populations abroad, including Cuba, was a manifestation of these conflicting allegiances. Despite the imperial dimensions of the Tuskegee connection to Cuba, it was not the product of U.S. imperialist designs. Instead, the relationship was created largely by the school and Afro-Cubans themselves. Rather than wage a counteroffensive to imperialism, the Tuskegee-Cuban connection shows how many Afro-diasporic subjects in Cuba and the United States attempted to take advantage of the opportunities created by the emerging imperial structure. Afro-Cubans and African Americans reached across national borders as a strategy to negotiate the changing configuration of power in a moment of imperial formation. To be sure, diasporization in the midst of empire was marked by unequal power relations; however, this does not negate the lasting effects of the Tuskegee-Cuba connection. Tuskegee remained an educational option for upwardly mobile Afro-Cubans into the 1920s. More importantly, it laid the foundation for Afro-diasporic interaction between Afro-Cubans and African Americans in subsequent decades.

Despite the apparent applicability of Washington's model of industrial education to Cuba, by and large his grand vision of Cuban Negroes studying at his school and returning to their homeland employing industrial methods did not come to pass in the ways he might have anticipated. Many Afro-Cuban students, like other pupils at the school, resisted Washington's rigorous curriculum and were expelled by the institution. Those who remained at the school and became loyal supporters of Tuskegee took apart their principal's message and clung to what they could use to their own purposes. Afro-Cuban alumni of the institution were empowered by Washingtonian racial uplift, not to become good farmers or domestic workers, but to become black professionals and entrepreneurs. Moreover, the emergence of Afro-Cuban institutions inspired by Washington, such as the Instituto Booker T. Washington in Havana, shows the influence of the Tuskegee principal's ideas even among those who never came to Tuskegee.

Analyzing the Tuskegee-Cuba relationship complicates our understanding of the transnational dimensions of African American history during the Jim Crow era. The basic assumptions that tended to guide interpretations of black American politics during the Jim Crow era characterized Washington and his followers as “accommodationists” while his rival W. E. B. Du Bois and his “Talented Tenth” adherents were positioned as more progressive (and internationalist) historical actors.4 These assumptions informed the most influential source on Washington and Tuskegee: the fourteen-volume published version of the Booker T. Washington Papers, compiled by Washington biographer Louis R. Harlan during the 1970s and 1980s.5 The few documents on Washington's effort to educate Afro-Cubans (and Afro–Puerto Ricans) that appear in the published volumes, as well as most subsequent scholarship, give the impression that Washington was little more than an agent of U.S. imperialism.6 Yet the published volumes, which contain approximately 5 percent of the entire collection housed at the Library of Congress, do not include a wealth of contrary evidence, especially the letters from students and others from Cuba and Puerto Rico who attended or expressed interest in attending the school. Therefore, giving attention to the archive beyond the published volumes opens up interpretations of the Tuskegee phenomenon that transcend the nation-based narrative of African American history.

A close examination of Tuskegee's connection to Cuba also enhances our knowledge of the ways Afro-Cubans experienced the imperial transition. As historians have shown, Cubans of African descent fought for their citizenship rights within the Cuban separatist movement and the newly formed Cuban republic.7 Yet, they also sought opportunities for themselves outside the confines of the Cuban state in formation. They had to. Even when they felt an intense investment in the Cuban nation, their uncertain material circumstances and the absence of local educational options compelled them to look elsewhere, particularly since the Cuban state was controlled by the U.S. occupation forces. The U.S. intervention and occupation of Cuba exacerbated racism on the island. Yet, it did not stop Afro-Cubans from pursuing openings in the emerging imperial structure for their own benefit. In this regard, Afro-Cubans were no different than other aspiring Cubans of this era.8

While the U.S. intervention in Cuba helped prompt Afro-Cubans to seek out Tuskegee for an education, it also provided openings for African Americans. While many African Americans were opposed to U.S. expansionism, others embraced it enthusiastically, especially when the “Spanish-American War” and the subsequent occupation of the island seemed to present new opportunities for material advancement and secure citizenship rights. Forging linkages with Afro-descended people abroad not only was the agenda of progressive (from a twenty-first-century perspective) Pan-Africanist intellectuals such as Du Bois, but was, in fact, part of the political and quotidian strategies of entrepreneurially minded African Americans such as those who considered themselves adherents of Booker T. Washington's ideas. Cuba's proximity to the United States and its centrality to the war effort made it particularly attractive for aspiring black men. If empire opened up new opportunities for many white Americans, it also opened up potential outlets, albeit more limited ones, to African Americans.

Tuskegee and the African Diaspora in the Age of Empire

In 1898, Booker T. Washington was on his way to becoming the most powerful black leader in the United States. His notoriety rapidly increased after his 1895 Atlanta Exposition address, also known as the Atlanta “Compromise” speech, in which he told a predominantly white Southern audience, “In all things purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Washington's stature was enhanced by the support of prominent figures among the white U.S. political and economic elite. After Washington's speech, many, if not all, roads led to the little town in the middle of the state of Alabama. Visitors and their money flowed into the school to see Washington's “miracle” of black education. Moreover, the annual Tuskegee Negro Conference, which attracted visitors to discuss the “Negro problem,” made it the de facto political center of black America in the opening decade of the century, whether his northern black elite opponents liked it or not. His ability to extract resources from philanthropists, including some leading industrialists, enabled him to make his educational institution, Tuskegee Institute, the most noteworthy school for people of African descent in the country at the time.

Tuskegee's emergence as a model of African American education enhanced Washington's stature, not just in the United States, but throughout the world. The Tuskegee principal was viewed by his admirers, black and white alike, as a leader of the “Negro race” worldwide. It was a role that he strategically embraced, even if he was a “provincial” man at heart.9 As European imperialism became more entrenched in Africa, white philanthropists and colonial officials saw the “Hampton-Tuskegee Idea” applicable to the African continent. European colonial officials were eager to apply Washington's model of “industrial education” to various educational and agricultural schemes in different parts of Africa.10 The institution's prestige was also enhanced by its hosting of the International Conference on the Negro in 1912, which included a wide range of participants who sought to apply Washington's model of industrial education to Africa and other parts of the diaspora. In the two decades before the emergence of Harlem as a black political and cultural capital, one could argue, Tuskegee was the prime epicenter of Afro-diasporic activity in the world.11

But Washington's international influence was first felt, not in Africa, but in the United States' “new possessions” in the Caribbean and the Pacific acquired in the War of 1898. As tensions between the United States and Spain escalated after the USS Maine exploded in February 1898, Washington and other African American leaders throughout the country saw the prospect of war presenting an opportunity to stake claims to equal citizenship. The eventual triumph of Jim Crow in the U.S. South has perhaps prompted us to overlook the fact that the impending war with Spain in 1898 seemed to offer a real possibility for African American men to stave off the onrushing tide of disfranchisement. Many saw the war as a moment when they could prove their worthiness for genuine political and social equality through their military service. Although black men had previously distinguished themselves in the Civil War and in the various wars against Native Americans, their participation in a military conflict with a foreign power could finally affirm African Americans' loyalty to the nation. Throughout the country, black activists called for the recruitment of African American volunteers into the armed forces. Such arguments were palpably gendered. Military service, as historian Michele Mitchell has shown, could not only further claims to full U.S. citizenship, but also enable black men to demonstrate their manhood. If white men in the United States and Europe could take up the “white man's burden,” African American men could make their own claim to imperial citizenship by articulating their own “black man's burden.” In this way, African American men sought to bring their aspirations for equal citizenship in the United States in line with their desires to play a leading role in the regeneration of the “race” as a whole.12

Booker T. Washington joined this chorus of African American voices agitating for participation in the conflict after the explosion of the Maine. In March 1898, he proposed to John Davis Long, the secretary of the navy, the idea of “placing at the service of the government at least ten thousand loyal, brave, strong black men in the South” for military service. Washington volunteered to take responsibility of this awesome task. He based his proposal on the racialist idea that black people could handle the tropical climate of Cuba better than whites. “The climate of Cuba is peculiar and dangerous to the un-acclimated white man,” the Tuskegee principal warned. Conversely, black soldiers would be ideal for the Cuban campaign because “the Negro race in the South is accustomed to this climate.”13 While federal and state leaders seem to have ignored Washington's proposal, President William McKinley eventually allowed African American men in select states to enlist as volunteers in the U.S. military later that year. The invading army included not only the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries, two regular black regiments, but also a number of newly formed volunteer infantries, including the Eighth Illinois, the Ninth “Immunes,” and the Twenty-third Kansas Infantry.14

As black men were volunteering for military service, the Tuskegee principal found himself in the position of a broker for U.S. interests in Cuba who needed “Negroes” for their projects on the island. As Washington's notoriety increased, many U.S. citizens sought him out to recommend black folks for work in the “new possessions.” As is generally known, powerful whites, including President Theodore Roosevelt, were asking Washington to recommend African Americans for government positions. Roosevelt was just one of hundreds who sought out Washington for guidance on how to incorporate “Negroes” into their plans. As the U.S. occupation of Cuba took shape, Washington received numerous requests from white missionary, charitable, and business organizations to recommend African Americans for their interests in Cuba. In November 1899, Osgood Welsh of the Constancia Sugar Company asked Washington to send to Cuba “a few proven men” to become “the advance guard of workers in the cane fields of the island.” However, Welsh made sure the Tuskegee principal understood that his interest in black workers was simply “a practical question of bringing together a supply and a demand.” Thus, Welsh informed Washington that while he “would have nothing to do with a sudden irruption in large numbers of American negroes into Cuba,” he would “under intelligent guidance bear a hand in making the experiment of enlarging the field of American negro work.”15

U.S. military officials stationed in Cuba also sought out the Negro race leader to inform him of opportunities for skilled African American workers in Cuba. Presley Holliday, the white sergeant major of the black Tenth Cavalry, informed Washington of the job prospects for tailors at his post in Manzanillo, Cuba. “Tailors are always in demand at posts garrisoned by the reg...