![]()

1: Education, Embodiment, and Epistemology

If the Qurʾan were on an untanned hide and was thrown into a fire, it would not burn.

—Saying attributed to the Prophet Muḥammad

The Taalibé’s Plight

A recent Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, Off the Backs of the Children: Forced Begging and Other Abuses against Talibés in Senegal, opens with these lines:

At least 50,000 children attending hundreds of residential Quranic schools, or daaras, in Senegal are subjected to conditions akin to slavery and forced to endure often extreme forms of abuse, neglect, and exploitation by the teachers, or marabouts. By no means do all Quranic schools run such regimes, but many marabouts force the children, known as talibés, to beg on the streets for long hours—a practice that meets the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) definition of a worst form of child labor—and subject them to often brutal physical and psychological abuse. The marabouts are also grossly negligent in fulfilling the children’s basic needs, including food, shelter, and healthcare, despite adequate resources in most urban daaras, brought in primarily by the children themselves.

This report is typical of how NGOS, human rights organizations, and casual observers have seen the daara. Its disclaimers not withstanding, HRW’S depiction of Qurʾan schooling, along with many others like it, conveys the notion that daaras offer no education worthy of the name and are sites only of child endangerment, abuse, and neglect. In such portrayals, Qurʾan teachers are accused of the most cynical forms of exploitation. HRW tells us that marabouts ought to be humble ascetics but are instead leading lives of wealth, ease, and comfort “Off the Backs of Children.” With no concrete fiscal data of any kind, the organization speculates freely about the sources and size of marabout revenues.1 Its policy recommendations include a United Nations investigation of daaras as a form of contemporary slavery but not aid for marabouts. When the latter receive assistance, HRW claims (again without evidence), they “do not adjust the practice of begging at all, but merely use the assistance to obtain even greater net income.”2 These tropes of slavery and cynical exploitation are linked to corporal discipline. Such “beatings,” as HRW calls them, are administered to force children to bring more money to their greedy, affluent marabouts:3 “Beatings were most frequently reported within the context of failing to return the daily quota, although there were tens of talibés who were also beaten for failure to master the Quranic verses.”4 The testimony of HRW’s child informants—that corporal discipline was meant to serve a pedagogic purpose—is dismissed.5

On alms seeking, child labor, and corporal punishment, as on many other topics, the report does not contextualize its data. Instead, HRW indulges in unsubstantiated claims about the quality of Qurʾanic education, which it does not attempt to measure or document in any way: “Tens of thousands of talibés in Senegal are failing to receive either a religious education or an education in other basic skills.”6 More troubling is that nowhere does HRW seriously ask why parents send their boys away to learn the Qurʾan in this way. The report’s authors acknowledge that nearly all students in such daaras were taken there by their parents, most of whom are fully cognizant of the hardships their children will endure.7 But this only leads them to condemn parents, too, making them coconspirators in child neglect and endangerment. Nowhere in “Off the Backs of the Children” does HRW come to terms with the fact that many parents are sending their sons to such schools because they want them to suffer significant hardship in their pursuit of Islamic knowledge. Nor do these outside observers grasp that marabouts are expected to discipline their charges, especially their live-in students (njàngaan).

The Untanned Hides of the Children of Adam

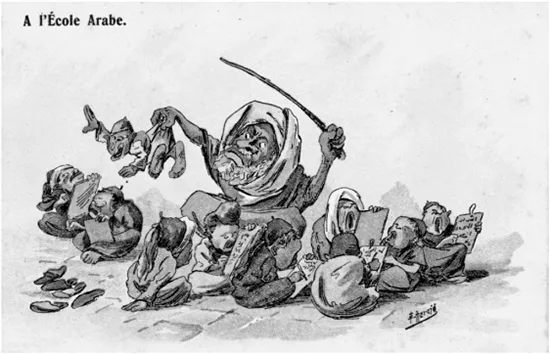

Such sensationalist depictions of the daara have drawn a fair amount of attention. In the process, they have helped raise advertising revenues for multimedia conglomerates and donations to human rights organizations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOS), and the numerous Christian mission groups that attempt to proselytize Muslim children in West Africa. The plight of the taalibé has become a cottage industry. In most cases, the outrage is certainly sincere and motivated by a desire to protect children, but it is based on a shallow understanding of what Qurʾan schooling means to—and does for—African Muslims. When the daara is framed in this way, religious freedoms and parents’ rights tend not to enter the equation. This kind of caricature of the daara did not originate with human rights groups. Senegalese colonial and postcolonial archives are full of government reports—beginning in the 1850s—that resemble Off the Backs of the Children. Attacks on Qurʾan schools were a major component of French assimilation policy and the colonial mission civilisatrice (civilizing mission) in Africa. My goal here is neither to rehash attacks on Qurʾan schools nor to highlight their imperialist precedents.8 Instead, I want to develop quite a different framework for understanding the disciplining of the body and the taming of the ego that take place in the daara.

Early twentieth-century postcard illustrated by cartoonist and colonist Édouard Herzig (1860–1926). Herzig, a white settler in Algeria, painted racial, cultural, and religious caricatures of North African Muslims. Colonial administrative reports on Qurʾan schooling in North and West Africa tended to exaggerate the themes he distorted visually here. Much contemporary reporting on Qurʾan schooling in West Africa does as well.

This chapter offers an interdisciplinary exploration of the epistemology of Qurʾan schooling. My analysis here is based largely on oral histories, autobiographical narratives, and archival accounts of dozens of students who grew up in Senegambian Qurʾan schools during the twentieth century. It is also informed by roughly three years of living in Senegal and participant observation in Muslim intellectual and social life. Finally, these sources are augmented by Arabic texts about—and practices of—schooling that range in time from the early days of Islam down to the present. These include hadith reports, teacher training manuals, treatises on the pursuit of knowledge, and other texts. My goal is to construct a kind of historical ethnography of the daara, the Senegambian Qurʾan school, in the past century or so and to use this portrait as a window onto the role of embodiment in Islamic epistemology.

This means paying careful attention to controversial practices within the daara—among them mendicancy and corporal punishment—and attempting to understand the role they play in schooling as well as the epistemology underlying them. In short, it means beginning our inquiry with how bodily discipline shapes lowly clay into the Walking Qurʾan. This brings us to the saying that opens this chapter. Many students who grew up in Senegambian Qurʾan schools in the twentieth century cited an aphorism (often purported to be a hadith) that any part of the body struck—or more specifically, scarred—while learning the Qurʾan would never burn in the hellfire. I have not yet found such a hadith, but in all likelihood, this was an oblique reference to the Prophetic saying that is the epigraph of this chapter: “If the Qurʾan were on an untanned hide and was thrown into a fire, it would not burn.”

Many classical theologians understood this saying to mean that the body of one who memorized the Qurʾan was exempt from the hellfire.9 Indeed, my interlocutors often discussed it in this context: people who had memorized the Qurʾan spoke of being promised freedom from the fire.10 This idea was sometimes discussed as a full-body absolution for the hāfiẓ, but more often it was represented as the liberation of the specific limbs that had been corporally chastised. It was as if the saving Word of God had been beaten into those pieces of flesh, thus sanctifying them. Some people showed me their scars, proudly or solemnly indicating where the short lashes often used in the daara had written the Qurʾan on their previously “untreated hides.”

Yar: Education, Discipline, and the Lash

West African Muslims have attached a profoundly positive value to suffering and hardship in pursuit of knowledge.11 In fact, in Wolof, the association of physical discipline with education is encoded even at the level of language. Contemporary Wolof speakers use the word yar primarily to mean “educate” or “raise.” It is also the most common noun meaning “education.” Yet the root meaning of the word yar is far more concrete—a “lash” or “switch.” Only by extension did the word come to mean discipline, moral education, and education more broadly. In the first-person testimonies, yar was a defining symbol of life in the Qurʾan school.12 An indication of its symbolic importance can be found in the illustrations that decorate the pages of the Cahiers Ponty. Three images far surpassed the others in frequency of represent...