![]()

Chapter 1: Not Blacks, but Citizens

Racial Rhetoric and the 1959 Revolution

During a heated televised interview on 25 March 1959, just three days after his first speech announcing the revolution’s campaign to eliminate racial discrimination, Cuban leader Fidel Castro had to defend his intentions against naysayers who disapproved of the new government’s integration plans. Castro recounted what he saw as a troubling event. He described a recent rally where audiences cheered wildly when he discussed lowering telephone taxes, reducing rents, and opening private beaches; yet the same crowd fell silent, or “made ugly faces” when he talked about “helping the negro.” After asking what the difference was between one injustice and the other, the young leader of the 26th of July Movement (M 26-7) concluded that the discrepancy resulted from “people who call themselves Christian and who are racist . . . people who call themselves revolutionaries but are racist . . . [and] people who call themselves good but are racist.”1 By openly critiquing Cubans for their hypocrisy and silence on racial inequality and publicly addressing the problems of people of color, Castro distinguished himself and other revolutionary leaders from past regimes.

Cuba’s state-sponsored campaign to eliminate racial discrimination began officially in March 1959, in response to pressure from Afro-Cuban groups demanding that racial justice be included in emerging revolutionary policies.2 “We have heard that Fidel Castro is thinking about this injustice . . . we hope that now we can begin to erase the discriminatory practices used by many people in business and industry,” wrote the presidents of the San Miguel de Padrón Social Union in February 1959.3 The following month, Castro made his first official announcement about the “hated injustice” of racial inequality. In front of thousands of Cubans, he outlined plans for blacks and whites to work and attend school together.4 Newspapers across the island reprinted Castro’s March speech and opened a brief three-year public dialogue about how to eliminate racial discrimination and ease racial tensions on the island. The official publication of M 26-7, Revolución, printed speeches from the rally under the headline, “A Million Workers: More United than Ever!” Revolución’s coverage of the event also included a small text box noting that the “Four Great Battles for the Well-being of the Cuban People” were to “1. Reduce unemployment; 2. Lower the cost of living; 3. Raise salaries of workers who earn the least; and 4. End racial discrimination in the work place.”5 Similarly, Noticias de Hoy, newspaper of the Cuban Communist Party (also known as the Partido Socialista Popular, or PSP, after 1944), published the 22 March speech under the headline, “In our country, of [Antonio] Maceo and [José] Martí, Oppression will not return.”6 Together, these headlines reveal key components of the young revolution’s racial rhetoric, specifically an emphasis on ending public discrimination in work centers and schools and the importance of mobilizing the legacies of nineteenth-century independence heroes to legitimize the new government and unify the population.

The revolution’s choice to speak to the unequal situation facing Cubans of color was somewhat surprising given M 26-7’s vagueness about race during the 1950s war against Fulgencio Batista. The guerillas’ platform and Castro’s speeches called for a return to the Constitution of 1940 and general social welfare reforms, but did not reference racial tensions in any substantive way. However, the need to unify the nation against U.S. opposition and respond to pressure from Afro-Cuban leaders led the post-1959 government to incorporate plans to eliminate discrimination into its public platform within months of taking power from Batista. In doing so, Castro built what would become the revolution’s legacy as an antiracist government and paved the way for Afro-Cuban defense of and defiance against the new government.

1950s Understandings of Race: M 26-7’s Platform vs. the Popular Press

Like political movements before them, M 26-7 was vague about its future plans to govern the island in the 1950s, especially in relation to racial politics. Castro, a member of the Orthodox Party, stepped into the spotlight of the anti-Batista coalition when he and a small group of rebels attacked the Moncada military barracks on 26 July 1953. The attack was a colossal failure, many died and even more were arrested, but as word spread about the uprising, Cubans rallied around the young men and women standing trial for treason against the state. In what would become one of his most famous speeches, “History Will Absolve Me,” Castro defended his actions to a full courtroom and defined his plans for building a new Cuba. “The problem of the land, the problem of industrialization, the problem of housing, the problem of unemployment, the problem of education, and the problem of people’s health: these are the six problems we would take immediate steps to solve along with restoration of civil liberties and political democracy.”7 Castro invoked statistics to paint a portrait of the hundreds of thousands of farmers without land, underpaid teachers, and rural laborers living in substandard housing who would benefit from his movement. However, despite the myriad of detail in the 189-page speech, the young rebel remained silent on the issue of racial discrimination—a topic he later promoted as strongly as he advocated for the more well-known Agrarian Reform. As historian Hugh Thomas notes, “To read ‘History Will Absolve Me’ would suggest that Castro was addressing a racially homogenous nation.”8

The absence of a specific program directed toward Afro-Cubans was especially glaring in comparison to the detailed ideological and political plans outlined in M 26-7’s Program Manifesto (1957). Listing the ten focal points of the revolution, including a desire for national sovereignty, an independent economy, and a strong education and employment sector, the Manifesto employed quotations from Martí to introduce each bullet point of the group’s platform. M 26-7 foreshadowed the type of postracial program Castro would later promote by using Martí’s words as a launching point for their policies. Because while the nineteenth-century Cuban patriot had emphasized the need to build a raceless Cuba after independence, a nation “without whites, without blacks, just Cubans,” Martí’s writings included few specifics about how to construct the idealized “nation for all.” In a similar manner, point number four of M 26-7’s Manifesto offered only a dim assessment of the island’s social inequalities and plans to tackle them. “From Martí, M 26-7 takes the position in respect to social problems. . . . In agreement with this concept, no group, class, race, or religion should put its interests over the common good, nor consider itself indifferent to the larger social order.”9 Like other pre-1959 references to discrimination, this statement placed racial prejudice among a long list of other intolerances. Only in the final pages of the Manifesto did the group mention plans to include an “educational plan for understanding others and racial integration.”10 As one of the more direct statements made by Castro and M 26-7 about race before overthrowing Batista, this declaration fit with their general ideological foundation mirroring that of nineteenth-century patriots. The young rebels repeatedly announced that they were completing the unfinished revolutions of 1868 and 1895; therefore their speeches and correspondence before 1959 rarely mentioned race outside of vague references to Martí’s language of “not rich or poor, not white or black.”11

And while M 26-7 did not directly address race or the situation of Afro-Cubans in public speeches or private correspondence, popular Cuban magazines, newspapers, and other political movements engaged with blackness and whiteness on a daily basis.12 Articles, advertisements, and political cartoons depicted blacks and mulatos “negatively” as either ignorant and poor, or “positively” for their physical strength and creative abilities using familiar colonial tropes. Cuba’s oldest general-interest magazine, Bohemia, was founded in 1908 and provided a weekly mix of contemporary political commentary, historical analysis, and up-to-date fashion advice. Despite having its editorial office in Havana, Bohemia’s circulation throughout the island meant that the magazine both reflected and influenced popular opinions nationwide. Bohemia reinforced notions of Afro-Cuban poverty and helplessness by printing images of homeless and poverty-stricken black communities or barrios humildes. The magazine frequently ran articles about unemployment and the plight of the urban and rural poor to highlight the economic challenges facing Cuba in the 1950s. Photographs of blacks and mulatos almost always accompanied these articles.13 Drawing attention to the poverty existing in some black neighborhoods was an important part of the magazine’s political commentary and social justice project; however, the lack of positive portrayals of Afro-Cubans to balance the pervasive visuals of black slums reaffirmed popular notions of blacks and mulatos as social pariahs.

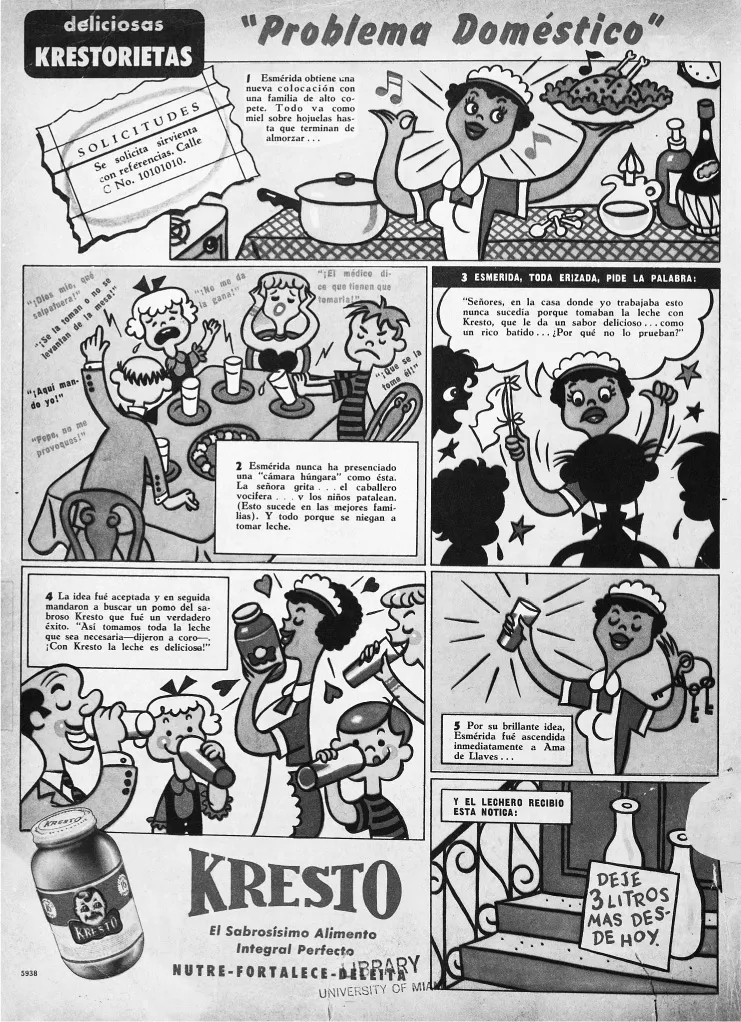

Cuban advertisers linked blackness to service positions in the 1950s using familiar race and class norms. Advertisements published in Bohemia built on consumer aspirations for a middle-class lifestyle and the very real economic hierarchies on the island where an overwhelming percentage of the domestic servants in white homes were Afro-Cuban.14 In a full-page color advertisement for Kresto, a sweet flavoring used to enhance the taste of milk, the company introduced the character of Esmérida, a brown-skinned Afro-Cuban maid, to promote their product (figure 1.1).15 The six-panel advertisement is structured like a comic strip and titled “Domestic Problem.” It paints a heteronormative lunch scene in a white family’s home where a business suit-clad father, a mother in a black gown, a blonde daughter, and an athletic son sit in the dining room while Esmérida, dressed in a recognizable white apron and maid’s hat, cooks and serves lunch. According to the advertisement, everything was going well until the meal ended and the whole family began to argue because the children did not want to drink their milk: “The Senora cried . . . the gentleman yelled, and the children fussed. (This happens in even the best families).” Esmérida assesses the scene and quickly intervenes by waving a white flag and offering a solution: “In other houses where I have worked, this [commotion] never happens because they drink their milk with Kresto, which gives it a delicious flavor.” The family agrees to try Kresto and in the final panels everyone (with the exception of Esmérida) happily consumes their beverages, while the text explains that for her “brilliant” idea the family promoted Esmérida and gave her the keys to the house. She becomes the “Ama de Llaves” (head domestic worker with access to the house’s keys).

Figure 1.1 “Domestic Problem.” Kresto milk flavoring advertisement. From Bohemia (4 January 1953). Courtesy of the Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami.

A number of themes about race in 1950s Cuba arise from this advertisement. Not only does the advertiser locate Esmérida as a lifelong servant who has held other domestic positions, the company also uses visual cues such as the expensive attire worn by the white family to contrast white economic success with black servitude. The advertisement invites readers to identify with upper-class leisure lifestyles by implying that it is advantageous to have a black maid not only for her cooking prowess, but also for her ability to solve domestic problems. And while the piece concludes by celebrating Esmérida and giving her new responsibilities in the home, her success is based on preparing, not participating in, the family meal. In her new position she continues to be cast as a grateful but accommodating subordinate as she is shown kissing the bottle of Kresto and beaming when she is given the keys to the house.

Other marketing campaigns also situated blackness and whiteness at opposite ends of the beauty and economic spectrum. Advertisers linked dark skin to domestic service and ugliness (via exaggerated black features) while setting fair skin and straight hair as the standard of Cuban beauty and financial success. To market the Tu-py brand of coffee, promoters introduced an Afro-Cuban waiter with dark skin and excessively full lips frozen in a wide smile (figure 1.2).16 The advertisers give the waiter the same name as the brand—the coffee and the black character that serves it are both identified as “Tu-py.” In doing so, they made it impossible for readers to distinguish the black male body from the product being promoted or the service he/it provides. Tu-py became even more of an unreal or invisible caricature in subsequent advertisements as the producers of the campaign alternated between representing him as a sketch (like a political cartoon) and using a photograph of a black minstrel doll. In each Tu-py ad, marketers reinforced the idea of Afro-Cubans, at worst, as nonhuman caricatures and, at best, as happy and contented servants by drawing blacks with oversized lips set in compliant grins.

Figure 1.2 “The best flavor of Tu-py: The preferred coffee everywhere.” From Bohemia (9 November 1952). Courtesy of the Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami.

In contrast, advertisers for Allyn’s hair-straightening cream sold their product, a chemical relaxer, using photographs of a white woman with long, shiny, dark hair (figure 1.3). This advertisement did not use a dark-skinned face or curly hair like the ones in the Kresto and Tu-py advertisements, despite claiming that the cream was created “especially for persons of color—men, women, and children.” Instead, Allyn’s cream relied on Cuban norms of Spanish fair-skinned and straight-haired beauty to encourage readers to strive for straighter tresses.17

Not all representations of Afro-Cubans in 1950s magazines followed these stereotypes of poverty, servitude, and unattractiveness. A few articles, especially those published each year in December commemorating the death of mulato general Antonio Maceo, recognized Afro-Cuban participation in the wars of independence and Cuba’s victory against Spain.18 One journalist highlighted how “the Habanero [Martí] and the spirited Oriental [Maceo] joined together as brothers and baptized the opposite poles of the country with their spilt blood” to reinforce the often repeated claim that the sacrifice of both Martí and Maceo erased the shame of slavery from the island and united the races in brotherly fraternity.19 Another article titled “The Past That Still Lives Today: The Death of Acea” described the valor and bravery of Colonel Isidro Acea, an Afro-Cuban soldier...