![]()

PART I

THE BRITISH

![]()

1

STRUCTURE, JURISDICTION, AND IDENTITY

The Geographical, Social, and Political Setting

Mandate Palestine was created in 1917. Before 1917, this territory (called Erets Yisraʾel in Hebrew) was part of the Ottoman Empire. It was divided into three different administrative units—thedistrict of Nablus, the district of Acre, and the subdistrict of Jerusalem.1 British troops stationed in Egypt occupied the southern part of Palestine in 1917 and conquered the northern part of the territory a year later. Palestine was first ruled by a military administration, but civil rule was established in 1920. Palestine was to be part of the mandate system created after the First World War. Unlike the colonial territories of the prewar era, the League of Nations granted mandate territories to Western powers, which were to serve as trustees, usually for a limited period of time, with the aim of eventually establishing self-rule by the local inhabitants. However, the “Mandate for Palestine,” formally granted to Britain by the League of Nations in 1922, did not simply envision eventual local independence. Instead, it required the British to assist in the establishment of a “Jewish national home” in Palestine.2

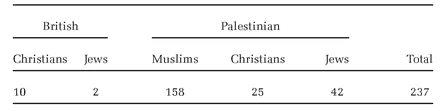

The three decades of British rule in Palestine saw accelerated economic and demographic growth that resulted, to a large extent, from the massive influx of Jewish capital and immigration. Between 1922 and 1944, the country’s population grew from about 750,000 to about 1,700,000 and the Jewish population grew from about 83,000 (10 percent of the population) to about 530,000 (30 percent of the population).3 Between the end of the First World War and the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, four massive waves of Jewish immigration occurred. The first wave occurred between 1919 and 1923 and consisted mostly of ideologically driven socialist workers and farmers from Russia. A second wave of Jewish immigration occurred between 1924 and 1932 and included mainly middle-class Polish Jews fleeing anti-Semitism and economic hardship. The third wave—mostly German Jews fleeing Nazism—occurred between 1933 and 1939. Finally, beginning in 1934 and intensifying after the end of the Second World War, Palestine saw the arrival of about 100,000 illegal Jewish immigrants, most of them Holocaust refugees. The different waves of immigration from different countries led to a large degree of cultural heterogeneity within Palestine’s Jewish community (table 1).

Table 1. Countries of Origin of Legal Jewish Immigration, 1919-1935

Source: Great Britain, Report 1936, 240.

| Country | Number of Legal Jewish Immigrants |

|---|

| Poland | 124,010 |

| Germany | 35,860 |

| Russia | 30,429 |

| Romania | 14,754 |

| Lithuania | 9,305 |

| Yemen | 8,529 |

| United States | 7,674 |

The country’s Arab population also underwent a process of transformation. Late Ottoman Arab society in Palestine was composed of a small upper class of Muslim urban notables, a small group of middle-class merchants (mainly Christians), and a very large group of poor and illiterate peasants and nomads. The thirty years of British rule witnessed a process of urbanization, as Arab peasants from the hills in the east of the country as well as from neighboring lands immigrated to the main cities on the coastal plains, Jaffa and Haifa. The mandate period also saw the emergence of a Muslim middle class composed of lawyers, civil servants, and teachers.4

Despite the ongoing transformation of Arab society during the years of British rule, profound economic and educational gaps existed between Arabs and Jews.5 The Arabs resented the growth of the Jewish community, viewing it as a threat to Arab aspirations for independence. Arab opposition to Zionism and to British rule led to brief but violent riots in 1920, 1921, and 1929, and a prolonged armed Arab rebellion occurred between 1936 and 1939. In May 1939, the British government published a policy statement (the “White Paper”) in which it renounced its obligations under the mandate to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine. The British promised to curtail Jewish immigration and restrict the sale of Arab land to Jews. The publication of the White Paper and the onset of the Second World War brought a period of relative calm to Palestine. Soon after the end of the war, however, the Jewish community began a rebellion against British rule, and in 1947, the British referred the matter of Palestine to the United Nations. In November of that year, the United Nations called for partition of the country. In May 1948, as the last British soldier left Palestine, the State of Israel was established, and a simmering civil war between Palestine’s Jewish and Arab communities morphed into the first full-blown Arab-Israeli war.

During the mandate, the country’s legal system underwent a process of partial transformation. The British expanded the jurisdiction of state courts and strengthened state control over religious courts and other informal tribunals. The British retained some of the legal rules and institutions that existed in the country during the Ottoman era and replaced others. The country’s legal system was thus remodeled from a system based on Islamic and French norms and procedures into one with significant common-law elements, a process often called Anglicization. The ultimate result of Anglicization was a system that was “a mosaic, a pattern made up of many legal pebbles: Ottoman, Muslim, French, Jewish and, above all, English.”6 The next four chapters will discuss Anglicization in great detail. This chapter’s concern is to describe the structure of Palestine’s courts. This structure was created in the late Ottoman era and in the first years of British rule and remained more or less stable for the rest of the mandate period.

The Legal System of Late Ottoman Palestine

During the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire underwent a series of reforms in an attempt to stem its decline in the face of growing European pressure. A major aspect of this process was legal reform. Prior to that period, law in the Ottoman Empire was based on religious Islamic law, but the reforms resulted in a partial secularization. The Ottomans enacted a number of codes (criminal, commercial, and procedural) inspired primarily by French law and codified Islamic civil law in the Mejelle. Religious courts, however, retained exclusive jurisdiction in family-law matters. Thus, when the British conquered Palestine, they found a hybrid system whose norms stemmed from three different sources: Islamic law, French law, and, in matters of family law, the law of each of Palestine’s religious communities.7

The court system of the late Ottoman Empire had a similar mixed nature. The Ottomans established a four-tiered secular court system: justices of the peace in principal towns; courts of first instance in the Ottoman subdistricts; courts of appeal in Ottoman districts; and, at the apex of the pyramid, a French-inspired Court of Cassation in Istanbul. In addition to the regular state courts and to Islamic, Jewish, and Christian religious courts dealing mostly with matters of personal status, the Ottomans created a number of specialized municipal and commercial courts.8 Some non-Muslims living in the empire enjoyed the benefits of the capitulation system, a set of special privileges that entitled holders to be tried in Western consular courts rather than in the regular state courts.9

It is hard to assess the efficiency of the Ottoman legal system in places such as Palestine. Some observers described the Ottoman courts of Palestine as inefficient and Ottoman judges as ignorant.10 Many Westerners believed that corruption was rife.11 Other observers, however, described the system as quite efficient.12 It would also be erroneous to assume that corruption disappeared when the British arrived.13

Legislation, the Attorney General, and the Legal Profession

During the first years of the occupation, the British maintained the legal status quo and retained Ottoman laws. However, because the terms of the mandate required that the British develop the country to facilitate the establishment of a Jewish national home, the British soon began to reform the Ottoman legal legacy, in major part through legislation. When the League of Nations granted Palestine to Britain in 1922, the British enacted the Palestine Order in Council, 1922, a constitutional document that outlined the structure of Palestine’s government. The Order in Council envisaged the establishment of a legislative council composed of British officials and elected local representatives. However, a dispute regarding the proportion of Jewish and Arab representatives in this body forced the British to vest legislative authority in the hands of the British high commissioner of Palestine. An advisory council composed entirely of government officials assisted the high commissioner in legislative matters.14

Table 2. Law and Justice Government Officials, 1920

Source: An Interim Report on the Civil Administration of Palestine during the Period 1 July 1920-30 June 1921 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1921), 25, reprinted in Jarman, Palestine and Transjordan Administration Reports.

The actual task of drafting government legislation was the responsibility of the attorney general and the Legal Department of the government of Palestine. Before legislation was enacted, the attorney general often conducted informal consultations with Arab and Jewish organizations. Legislation also required the approval of the Colonial Office in London. In addition to drafting legislation and advising the government, the attorney general supervised land and other commercial registers, oversaw public prosecutions, represented the government in the courts, supervised legal education, and conducted examinations for the local bar. The power to administer and supervise government courts in Palestine was vested in the chief justice, who was independent of the executive and ranked second to the high commissioner.15 The total number of government officials dealing with legal matters (including judges) was quite small, and most of these officials were not British but Palestinian (table 2).

Late Ottoman Palestine had very few lawyers, and the numbers declined during the First World War.16 By the time the British occupied Palestine in 1917, the number of lawyers remaining in the country “could be counted on the fingers of two hands.”17 After the end of the war, however, those numbers steadily grew, and by the end of 1920, nearly a hundred lawyers had registered, most of them Arab and most without any formal legal education. Of the few lawyers that had such an education, some had studied in Ottoman law schools, while a few were British or British-trained.18 As in many other colonies, Palestine’s legal profession was “fused”—that is, the English distinction between solicitors and barristers was not used, and any advocate could appear before the courts.19 In November 1920 the British opened a law school in Jerusalem known as the Law Classes. In the 1920s about 150 Jewish and Arab students were enrolled, with about forty students in each year of the three- (and later four-) year course of study. In 1922, the British formed the Legal Board (later called the Legal Council) to supervise professional conduct as well as the licensing of advocates. An examination in the law of Palestine and two years of service in the office of a practicing advocate were required to obtain a license.20 In 1922 the first local Jewish bar association was established, and a national Jewish bar association was formed in 1928. A national (but inactive) Arab bar association was established in 1945.21 Throughout the mandate, an influx of foreign Jewish lawyers into the country occurred, many of them from Germany. These lawyers were required to pass a special examination for foreign lawyers before being allowed to practice law in Palestine. By the end of the mandate, about one thousand lawyers were practicing in Palestine, the majority of them Jews (table 3).22

Table 3. Number of Lawyers Practicing before the Civil Courts of Palestine

| Year | Jews | Non-Jews |

|---|

| 1922 | 38 | 85 |

| 1931 | 137 | 93 |

| 1937 | 246 | 112 |

| 19481 | Over 500 | ca. 500 |

| Sources: Reid, Lawyers, 314; Keith-Roach, Pasha, 85; CZA J 108/12, Histadrut Orkhe ha-Din ha-Yehudim be-Erets Yisra‘el: Protocol ha-Moʿetsa ha-Shishit (Jewish Bar Association: Protocol of the Sixth Council), 4 April 1937. |

| 1The numbers for 1948 are based on Reid, Lawyers. |

Although no unified Arab-Jewish lawyers’ association existed and despite political tensions, Arab-Jewish legal cooperation was quite common, and professional alliances often cut across ethnic divisions. Arab and Jewish organizations sometimes cooperated in professional matters.23 Arab-Jewish law partnerships existed, and Arab judges often decided cases involving Jews and vice versa.24 While there are no comprehensive quantitative studies of cross-community representation, a sample study of reported Supreme and District Court decisions from the 1930s and 1940s reveals that about 10 percent of the litigants were represented by lawyers belonging to the other community.25

Cooperation also extended beyond the purely professional sphere. Some of Palestine’s leading Jewish lawyers, such as Gad Frumkin, the only Jewish Supreme Court judge, had been born in Ottoman Palestine and had grown up i...