![]()

What are we made of?

It’s probably fair to say that we may live a reasonably enjoyable, profitable, and/or meaningful life without knowing the answer to the question: “What is a quark?”

However, if you should stop to think …

… you will have inadvertently embarked on one of the greatest intellectual, philosophical and scientific journeys it is possible to make.

Philosophy: mind and matter

Traditionally, questions like “What are we made of?” were the domain of philosophers. A famous early attempt at an answer can be found in Plato’s Timaeus (c. 360 BC).

Furthermore, these elements were thought themselves to be made of the Platonic solids (the friendliest of the shapes). In Plato’s theory of everything, earth is made of stackable cubes, the relative compactness of the octahedron lends itself naturally to the air we find all around us, icosahedra flow much as we would expect water to, and the sharpness of the tetrahedron neatly explains why fire hurts when we touch it. (A fifth element, the “aether”, was added by Aristotle to give perfect, unspoilable substance to the heavens.)

Such a theory may well seem like it was formulated in a pub (or the classical equivalent), but even as late as the 18th century, ideas such as Descartes’ Dualism (La Description du Corps Humain, 1647) and Leibniz’s Monads (La Monadologie, 1714) persisted as seemingly reasonable attempts to describe reality.

Metaphysics

With his elements, Plato was trying to understand what the world was made of. Descartes’ Dualism went further, arguing that the stuff that lets us think is different to the stuff we’re made of. This division of all things into mind or matter is a great example of metaphysics – the branch of philosophy that aims to describe and understand all the aspects of what it means to “be”.

And as long as all you’re doing is a little postulation and pontification, there’s nothing wrong with that.

Empiricism

It was with the birth of John Locke’s empiricism* in the 17th century that thinkers started acknowledging that checking one’s ideas against experience might be worthwhile.

This conforms to our modern definition of science and the practice of the scientific method. However, until the 19th century “science” simply meant “knowledge”. The term “natural philosophy” was used to describe purely theoretical musings on the workings of the world.

Experimental philosophy

Lord Kelvin (1824–1907, born William Thomson) established the first university physics laboratory in Scotland, the spiritual home of empiricism. Here, ideas could be tested scientifically.

We have come a long way since the time of brilliant individuals working in what were little more than sheds in the grounds of universities. Experiments at the frontiers of our knowledge now need investments of millions – if not billions – of dollars in Bond villain-esque facilities and equipment, and world-wide networks of computing power for data storage and processing.

And yet, in many ways, modern particle physics retains the spirit of metaphysics. It probes our concept of what is real. One may complain that it’s unfair to stunt the creativity of the human imagination by testing its musings against something as trivial as “reality”. I prefer to think of it just as working out, as best we can, what’s really going on. So far, by testing our ideas with experiments, we have witnessed the triumph of matter over mind.

Figuring out the code

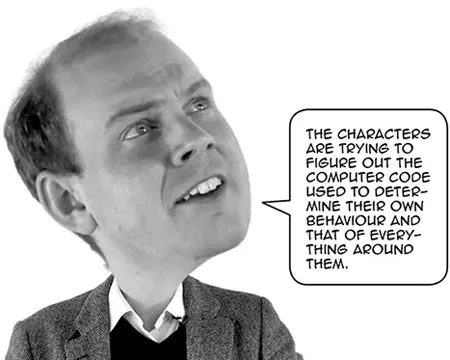

The great Richard Feynman (1918–88), who shared a Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to experimental philosophy, once described science as like trying to figure out the rules of chess by watching a game being played.

The journey described in this book is perhaps more akin to that of a group of characters in a computer game.

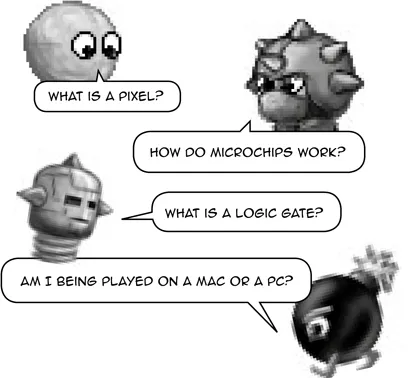

But in terms of this book’s subject matter, I’d expand on the analogy a little. The characters can go further. They can ask:

Likewise, all of the scientific equipment we use is made of the same stuff that we’re trying to find out about, as are the laboratories in which the experiments are performed, as are the scientists performing the experiments – as are you, reading of their efforts and achievements on these pages.

We are not watching the game. We are in the game.

The first atomist

Where did our journey begin? I’d argue that “particle physics” began when we figured out that the atom – the indivisible unit of stuff of which all things are made – is, in fact, divisible. To appreciate the seismic shift this represented in our thinking, we need to understand the theory itself and the historical context.

We’ve already come across one of the first theories of matter – the elements of Plato’s Timaeus.

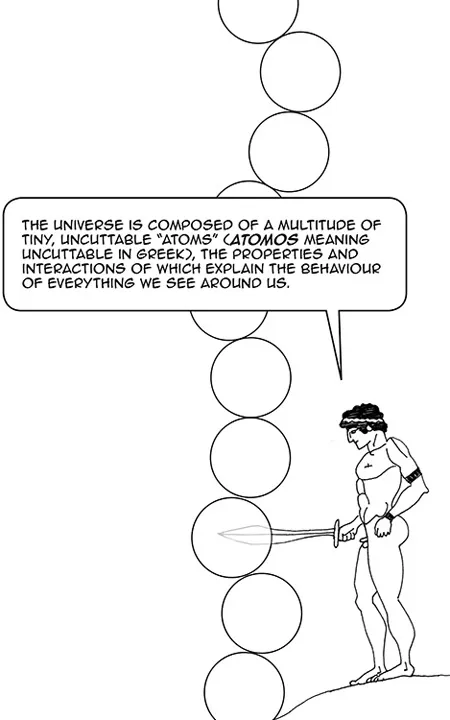

You are probably more familiar with the atomic theory attributed to Thracian philosopher Democritus (460–370 BC).

Democritus was the first atomist and, as we shall see, his idea has successfully weathered the tests of both time and experiment. The alternative...