- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

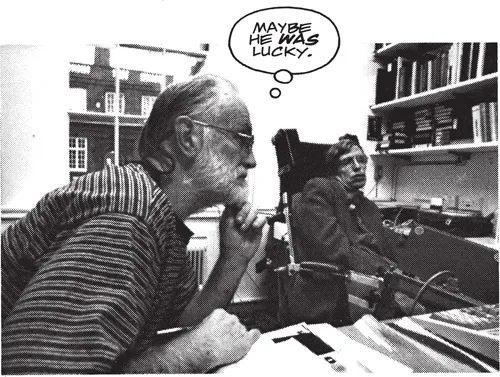

'An ideal introduction [to Stephen Hawking]' - Independent 'Astonishingly comprehensive - clearer than Hawking himself' - Focus

Stephen Hawking was a world-famous physicist with a cameo in The Simpsons on his CV, but outside of his academic field his work was little understood. To the public he was a tragic figure - a brilliant scientist and author of the 9 million-copy-selling A Brief History of Time, and yet spent the majority of his life confined to a wheelchair and almost completely paralysed.Hawking's major contribution to science was to integrate the two great theories of 20th-century physics: Einstein's General Theory of Relativity and Quantum Mechanics.J.P. McEvoy and Oscar Zarate's brilliant graphic guide explores Hawking's life, the evolution of his work from his days as a student, and his breathtaking discoveries about where these fundamental laws break down or overlap, such as on the edge of a Black Hole or at the origin of the Universe itself.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

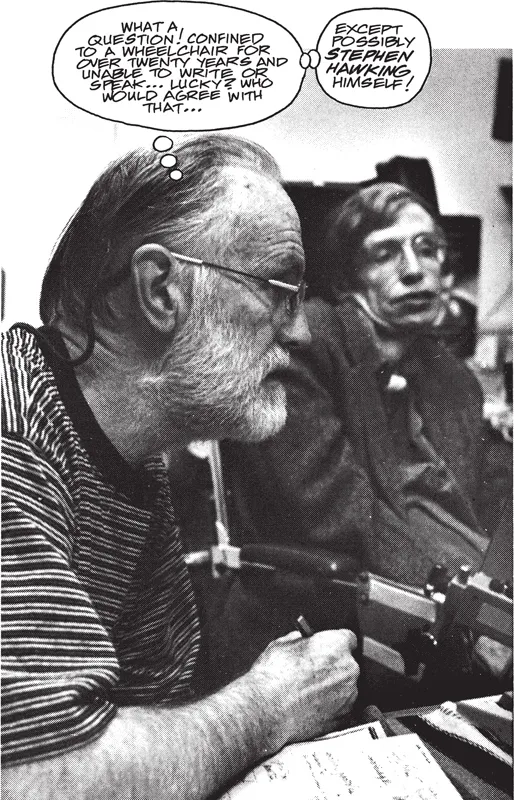

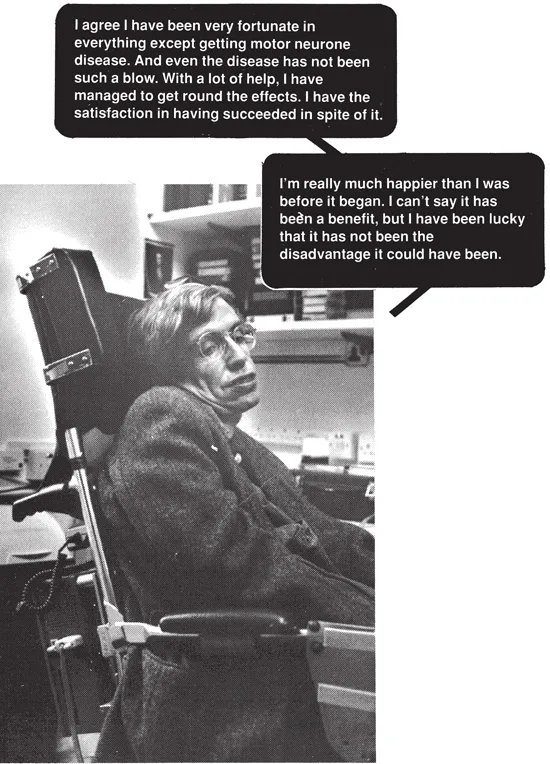

The Luckiest Man in the Universe

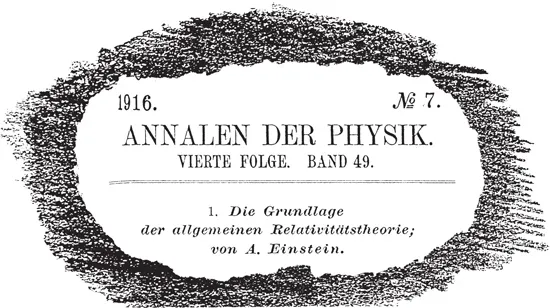

The General Theory of Relativity

- First, major breakthroughs in observational astronomy – reaching out to the most distant galaxies – have made the Universe a laboratory to test cosmological models

- Second, Einstein’s general relativity has been proven over and over again to be an accurate and reliable theory of gravitation throughout the entire Universe.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- The Luckiest Man in the Universe

- The General Theory of Relativity

- Newton: The Concept of Force

- Four Kinds of Force in the Universe

- The Principia: Describing Newton’s Universe

- Newton and Hawking

- The Concept of Mass

- Albert Einstein, the Saviour of Classical Physics

- Einstein and Hawking

- Einstein’s Happiest Thought

- Finding the Right Equation

- The Field Equations – What do they mean?

- Visualising Curved Space: the Rubber Sheet Model

- The Bending of Starlight: Eclipse of 29 May 1919

- Solving Einstein’s Equations: Hawking’s Starting Material

- 1) The Schwarzschild Geometry

- The Critical Radius

- 2) Friedmann: the Expanding Universe

- Precursor to the Big Bang: Lemaître’s Primordial Aim

- 3) Oppenheimer: on Continued Gravitational Collapse, 1939

- 1 September 1939

- 1942 … A Turning Point in the Story

- The Death of Einstein

- The Hawking Era

- The Unselfish Thesis Supervisor

- Something You Need to Know: What is a Singularity?

- The Evolution of the Universe

- 1965: a Big Year for Hawking

- An Unstoppable Mind

- The Sixties Revolution

- Dallas 1963

- Something You Need to Know: the Electro Magnetic Spectrum

- 1963: Quasars

- 1965: the Cosmic Background Radiation

- Something You Need to Know — Thermal Radiation

- History of the Universe

- Black Holes — Wheeler Gives the Media a Buzz Word

- The Age of Black Holes

- What is a Black Hole ?

- The Birth and Death of Stars

- The Laws of Thermodynamics

- How Stars Collapse to Form White Dwarfs, Neutron Stars & Black Holes

- Observational Evidence for Black Holes

- The 1970s: Hawking and Black Holes

- Hawking’s Eureka Moment

- Now Back to Black Holes …

- Controversial Birth of a New Idea

- August 1972, Les Houches Summer School on Black Hole Physics

- The Uncertainty Principle & Virtual Particles

- February 1974, The Rutherford- Appleton Laboratory, Oxford

- Hawking and the Vatican – a Modern Day Galileo

- Hawking and the Early Universe

- Why Do We Need Quantum Theory?

- Quantum Cosmology

- Quantum Gravity or TOE

- Quantum Cosmology and Complex Time

- Waves and Particles: Nature’s Joke on the Physicists

- The Strange World of Quantum Mechanics

- Quantum Cosmology: Applying Schrödinger’s Equation to the Universe

- DAMTP: 17 February 1995

- Inflation

- Inflation and Quantum Fluctuations

- The Anthropic Principle

- Hawking’s Nobel Prize

- COBE: the Greatest Discovery of All Time (?)

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app