eBook - ePub

In Search of Excellence

Thomas J. Peters, Robert H. Waterman, Jr.

This is a test

Share book

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

In Search of Excellence

Thomas J. Peters, Robert H. Waterman, Jr.

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The "Greatest Business Book of All Time" (Bloomsbury UK), In Search of Excellence has long been a must-have for the boardroom, business school, and bedside table.

Based on a study of forty-three of America's best-run companies from a diverse array of business sectors, In Search of Excellence describes eight basic principles of management -- action-stimulating, people-oriented, profit-maximizing practices -- that made these organizations successful.

Joining the HarperBusiness Essentials series, this phenomenal bestseller features a new Authors' Note, and reintroduces these vital principles in an accessible and practical way for today's management reader.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is In Search of Excellence an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access In Search of Excellence by Thomas J. Peters, Robert H. Waterman, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Leadership. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BetriebswirtschaftSubtopic

LeadershipPART ONE

THE SAVING REMNANT

1

Successful American Companies

The Belgian Surrealist René Magritte painted a series of pipes and entitled the series Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe). The picture of the thing is not the thing. In the same way, an organization chart is not a company, nor a new strategy an automatic answer to corporate grief. We all know this; but like as not, when trouble lurks, we call for a new strategy and probably reorganize. And when we reorganize, we usually stop at rearranging the boxes on the chart. The odds are high that nothing much will change. We will have chaos, even useful chaos for a while, but eventually the old culture will prevail. Old habit patterns persist.

At a gut level, all of us know that much more goes into the process of keeping a large organization vital and responsive than the policy statements, new strategies, plans, budgets, and organization charts can possibly depict. But all too often we behave as though we don’t know it. If we want change, we fiddle with the strategy. Or we change the structure. Perhaps the time has come to change our ways.

Early in 1977, a general concern with the problems of management effectiveness, and a particular concern with the nature of the relationship between strategy, structure, and management effectiveness, led us to assemble two internal task forces at McKinsey & Company. One was to review our thinking on strategy, and the other was to go back to the drawing board on organizational effectiveness. It was, if you like, McKinsey’s version of applied research. We (the authors) were the leaders of the project on organizational effectiveness.

A natural first step was to talk extensively to executives around the world who were known for their skill, experience, and wisdom on the question of organizational design. We found that they, too, shared our disquiet about conventional approaches. All were uncomfortable with the limitations of the usual structural solutions, especially the latest aberration, the complex matrix form. Yet they were skeptical about the usefulness of any known tools, doubting they were up to the task of revitalizing and redirecting billion-dollar giants.

In fact, the most helpful ideas were coming from the strangest places. Way back in 1962, the business historian Alfred Chandler wrote Strategy and Structure, in which he expressed the very powerful notion that structure follows strategy. And the conventional wisdom in 1977, when we started our work, was that Chandler’s dictum had the makings of universal truth. Get the strategic plan down on paper and the right organization structure will pop out with ease, grace, and beauty. Chandler’s idea was important, no doubt about that; but when Chandler conceived it everyone was diversifying, and what Chandler most clearly captured was that a strategy of broad diversification dictates a structure marked by decentralization. Form follows function. For the period following World War II through about 1970, Chandler’s advice was enough to cause (or maintain) a revolution in management practice that was directionally correct.

But as we explored the subject, we found that strategy rarely seemed to dictate unique structural solutions. Moreover, the crucial problems in strategy were most often those of execution and continuous adaptation: getting it done, staying flexible. And that to a very large extent meant going far beyond strategy to issues of organizing — structure, people, and the like. So the problem of management effectiveness threatened to prove distressingly circular. The dearth of practical additions to old ways of thought was painfully apparent. It was never so clear as in 1980, when U.S. managers, beset by obvious problems of stagnation, leaped to adopt Japanese management practices, ignoring the cultural difference, so much wider than even the vast expanse of the Pacific would suggest.

Our next step in 1977 was to look beyond practicing businessmen for help. We visited a dozen business schools in the United States and Europe (Japan doesn’t have business schools). The theorists from academe, we found, were wrestling with the same concerns. Our timing was good. The state of theory is in refreshing disarray, but moving toward a new consensus; some few researchers continue to write about structure, particularly that latest and most modish variant, the matrix. But primarily the ferment is around another stream of thoughts that follows from some startling ideas about the limited capacity of decision makers to handle information and reach what we usually think of as “rational” decisions, and the even lesser likelihood that large collectives (i.e., organizations) will automatically execute the complex strategic design of the rationalists.

The stream that today’s researchers are tapping is an old one, started in the late 1930s by Elton Mayo and Chester Barnard, both at Harvard. In various ways, both challenged ideas put forward by Max Weber, who defined the bureaucratic form of organization, and Frederick Taylor, who implied that management really can be made into an exact science. Weber had pooh-poohed charismatic leadership and doted on bureaucracy; its rule-driven, impersonal form, he said, was the only way to assure long-term survival. Taylor, of course, is the source of the time and motion approach to efficiency: if only you can divide work up into enough discrete, wholly programmed pieces and then put the pieces back together in a truly optimum way, why then you’ll have a truly top-performing unit.

Mayo started out four-square in the mainstream of the rationalist school and ended up challenging, de facto, a good bit of it. On the shop floors of Western Electric’s Hawthorne plant, he tried to demonstrate that better work place hygiene would have a direct and positive effect on worker productivity. So he turned up the lights. Productivity went up, as predicted. Then, as he prepared to turn his attention to another factor, he routinely turned the lights back down. Productivity went up again! For us, the very important message of the research that these actions spawned, and a theme we shall return to continually in the book, is that it is attention to employees, not work conditions per se, that has the dominant impact on productivity. (Many of our best companies, one friend observed, seem to reduce management to merely creating “an endless stream of Hawthorne effects.”) It doesn’t fit the rationalist view.

Chester Barnard, speaking from the chief executive’s perspective (he had been president of New Jersey Bell), asserted that a leader’s role is to harness the social forces in the organization, to shape and guide values. He described good managers as value shapers concerned with the informal social properties of organization. He contrasted them with mere manipulators of formal rewards and systems, who dealt only with the narrower concept of short-term efficiency.

Barnard’s concepts, although quickly picked up by Herbert Simon (who subsequently won a Nobel prize for his efforts), lay otherwise dormant for thirty years while the primary management disputes focused on structure attendant to postwar growth, the burning issue of the era.

But then, as the first wave of decentralizing structure proved less than a panacea for all time and its successor, the matrix, ran into continuous troubles born of complexity, Barnard and Simon’s ideas triggered a new wave of thinking. On the theory side, the exemplars were Karl Weick of Cornell and James March of Stanford, who attacked the rational model with a vengeance.

Weick suggests that organizations learn and adapt v-e-r-y slowly. They pay obsessive attention to habitual internal cues, long after their practical value has lost all meaning. Important strategic business assumptions (e.g., a control versus a risk-taking bias) are buried deep in the minutiae of management systems and other habitual routines whose origins have long been obscured by time. Our favorite example of the point was provided by a friend who early in his career was receiving instruction as a bank teller. One operation involved hand-sorting 80-column punched cards, and the woman teaching him could do it as fast as lightning. “Bzzzzzzt” went the deck of cards in her hands, and they were all sorted and neatly stacked. Our friend was all thumbs.

“How long have you been doing this?” he asked her.

“About ten years,” she estimated.

“Well,” said he, anxious to learn, “what’s that operation for?”

“To tell you the truth” — Bzzzzzzt, another deck sorted — “I really don’t know.”

Weick supposes that the inflexibility stems from the mechanical pictures of organizations we carry in our heads; he says, for instance: “Chronic use of the military metaphor leads people repeatedly to overlook a different kind of organization, one that values improvisation rather than forecasting, dwells on opportunities rather than constraints, discovers new actions rather than defends past actions, values arguments more highly than serenity and encourages doubt and contradiction rather than belief.”

March goes even further than Weick. He has introduced, only slightly facetiously, the garbage can as organizational metaphor. March pictures the way organizations learn and make decisions as streams of problems, solutions, participants, and choice opportunities interacting almost randomly to carry the organization toward the future. His observations about large organizations recall President Truman’s wry prophecy about the vexations lying in wait for his successor, as recounted by Richard E. Neustadt. “He’ll sit here,” Truman would remark (tapping his desk for emphasis), “and he’ll say, ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen. Poor Ike — it won’t be a bit like the army. He’ll find it very frustrating.”

Other researchers have recently begun to accumulate data that support these unconventional views. The researcher Henry Mintzberg, of Canada’s McGill University made one of the few rigorous studies of how effective managers use their time. They don’t regularly block out large chunks of time for planning, organizing, motivating, and controlling, as most authorities suggest they ought. Their time, on the contrary, is fragmented, the average interval devoted to any one issue being nine minutes. Andrew Pettigrew, a British researcher, studied the politics of strategic decision making and was fascinated by the inertial properties of organizations. He showed that companies often hold on to flagrantly faulty assumptions about their world for as long as a decade, despite overwhelming evidence that that world has changed and they probably should too. (A wealth of recent examples of what Pettigrew had in mind is provided by the several American industries currently undergoing deregulation — airlines, trucking, banks, savings and loans, telecommunications.)

Among our early contacts were managers from long-term top-performing companies: IBM, 3M, Procter & Gamble, Delta Airlines. As we reflected on the new school of theoretical thinking, it began to dawn on us that the intangibles that those managers described were much more consistent with Weick and March than with Taylor or Chandler. We heard talk of organizational cultures, the family feeling, small is beautiful, simplicity rather than complexity, hoopla associated with quality products. In short, we found the obvious, that the individual human being still counts. Building up organizations that take note of his or her limits (e.g., information-processing ability) and strengths (e.g., the power flowing from commitment and enthusiasm) was their bread and butter.

CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS

For the first two years we worked mainly on the problem of expanding our diagnostic and remedial kit beyond the traditional tools for business problem solving, which then concentrated on strategy and structural approaches.

Indeed, many friends outside our task force felt that we should simply take a new look at the structural question in organizing. As decentralization had been the wave of the fifties and sixties, they said, and the so-called matrix the modish but quite obviously ineffective structure of the seventies, what then would be the structural form of the eighties? We chose to go another route. As important as the structural issues undoubtedly are, we quickly concluded that they are only a small part of the total issue of management effectiveness. The very word “organizing,” for instance, begs the question, “Organize for what?” For the large corporations we were interested in, the answer to that question was almost always to build some sort of major new corporate capability — that is, to become more innovative, to be better marketers, to permanently improve labor relations, or to build some other skill which that corporation did not then possess.

An excellent example is McDonald’s. As successful as that corporation was in the United States, doing well abroad meant more than creating an international division. In the case of McDonald’s it meant, among other things, teaching the German public what a hamburger is. To become less dependent on government sales, Boeing had to build the skill to sell its wares in the commercial marketplace, a feat most of its competitors never could pull off. Such skill building, adding new muscle, shucking old habits, getting really good at something new to the culture, is difficult. That sort of thing clearly goes beyond structure.

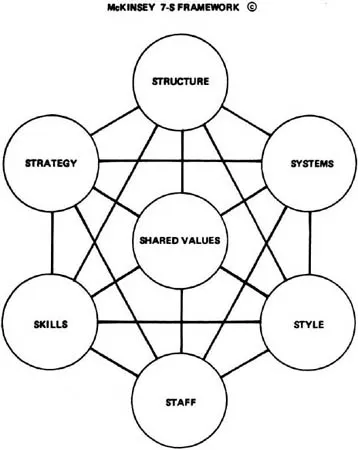

So we needed more to work with than new ideas on structure. A good clue to what we were up to is contained in a remark by Fletcher Byrom, chairman and chief executive of Koppers: “I think an inflexible organization chart which assumes that anyone in a given position will perform exactly the same way his predecessor did, is ridiculous. He won’t. Therefore, the organization ought to shift and adjust and adapt to the fact that there’s a new person in the spot.” There is no such thing as a good structural answer apart from people considerations, and vice versa. We went further. Our research told us that any intelligent approach to organizing had to encompass, and treat as interdependent, at least seven variables: structure, strategy, people, management style, systems and procedures, guiding concepts and shared values (i.e., culture), and the present and hoped-for corporate strengths or skills. We defined this idea more precisely and elaborated what came to be known as the McKinsey 7-S Framework (see figure on next page). With a bit of stretching, cutting, and fitting, we made all seven variables start with the letter S and invented a logo to go with it. Anthony Athos at the Harvard Business School gave us the courage to do it that way, urging that without the memory hooks provided by alliteration, our stuff was just too hard to explain, too easily forgettable.

Hokey as the alliteration first seemed, four years’ experience throughout the world has borne out our hunch that the framework would help immeasurably in forcing explicit thought about not only the hardware — strategy and structure — but also about the software of organization — style, systems, staff (people), skills, and shared values. The framework, which some of our waggish colleagues have come to call the happy atom, seems to have caught on around the world as a useful way to think about organizing.* Richard Pascale and Anthony Athos, who assisted us in our concept development, used it as the conceptual underpinning for The Art of Japanese Management. Harvey Wagner, a friend at the University of North Carolina and an eminent scholar in the hard-nosed field of decision sciences, uses the model to teach business policy. He said recently, “You guys have taken all the mystery out of my class. They [his students] use the framework and all the issues in the case pop right to the surface.”

In retrospect, what our framework has really done is to remind the world of professional managers that “soft is hard.” It has enabled us to say, in effect, “All that stuff you have been dismissing for so long as the intractable, irrational, intuitive, informal organization can be managed. Clearly, it has as much or more to do with the way things work (or don’t) around your companies as the formal structures and strategies do. Not only are you foolish to ignore it, but here’s a way to think about it. Here are some tools for managing it. Here, really, is the way to develop a new skill.”

But there was still something missing. True, we had expanded our diagnostic tool kit by quantum steps. True, we had observed managers apparently getting more done because they could pay attention with seven S’s instead of just two. True, by recognizing that real change in large institutions is a function of at least seven hunks of complexity, we were made appropriately more humble about the difficulty of changing a large institution in any fundamental way. But, at the same time, we were short on practical design ideas, especially for the “soft S’s.” Building new corporate capability wasn’t the simple converse of describing and understanding what’s not working, just as designing a good bridge takes more than understanding why some bridges fail. We now had far better mental equipment for pinpointing the cause of organizational malaise, which was good, and we had enhanced our ability to determine what was working despite the structure and ought to be left alone, which was even better. But we needed to enrich our “vocabulary” of design patterns and ideas.

Accordingly, we decided to take a look at management excellence itself. We had put that item on the agenda early in our project, but the real impetus came when the managing directors of Royal Dutch/Shell Group asked us to help them with a one-day sem...