![]()

CHAPTER 1

“THEIRS NOT TO REASON WHY”

New York Harbour, November 30, 1917

What had he gotten himself into? Captain Aimé Le Médec had been on the job for eleven years. He had always been supremely confident of his ability to meet any challenges that man or the sea threw at him. Until now. Le Médec knew—only too well—the dangers of the voyage upon which he and his men were about to embark. There was no question this was his most dangerous assignment ever. Nor was there any question that this was one trans-Atlantic crossing he was not eager to make.

The captain was a brave man; cowards and nervous Nellies tend not to become mariners. At age thirty-nine, Le Médec had no burning desire to be a hero, but he knew he had no say in the cargo his ship carried.

Orders were orders, and the captain accepted that he must obey them, especially in wartime. As the master of a lowly tramp steamer and an officer of the French naval reserve, Le Médec was subject to military discipline and to punishment, if ever it came to that. The punishment for insubordination, mutiny, or desertion would be prison, if he was lucky. If he was not, could it be a firing squad, he wondered? But none of that mattered. Le Médec was a patriot. He would do his duty for France.

The captain’s superiors had directed him to deliver a load of munitions from New York to the killing fields of Western Europe, and he would do so. Le Médec remembered what that Englishman, the poet Lord Tennyson, had mused in his famous poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade”: “Theirs not to make reply, / Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die.”

Instant obliteration. That was the terrifying prospect Captain Aimé Le Médec and his forty-man crew faced as their plodding ship prepared to steam out of New York harbour. They were bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then, it would be on to their home port of Bordeaux. That is, if the SS Mont-Blanc was lucky enough to make it that far.

The members of the ship’s crew, French citizens with a few colonials mixed in, were aware to a man that theirs were le salaire de la peur—the wages of fear. Besides having to run the usual wartime gauntlet of German U-boats that lurked in the depths of the North Atlantic, they faced additional danger on this trip. Packed to the gunwales, the ship was carrying more than enough munitions and barrels of high-octane benzol fuel to blow the ship and all souls on board her into eternity, and perhaps beyond, in the blink of an eye.

After more than three years of bloodletting in Europe, Germany had made a desperate and ultimately ill-advised decision to initiate unrestricted submarine warfare in the sea lanes between North America and Europe. That move had brought the United States into the war on the side of the Allies on April 6, 1917. Once that happened, New York City became a major port of embarkation for Allied troops, supplies, and munitions bound for the Western Front. The already busy waters in and around New York teemed with wartime traffic.

Most seafarers believed the harbour there was too shallow, too murky, for even the most daring of U-boat commanders to venture into. American military officials were not so sure of that; the German enemy was as devious as he was ruthless. The United States navy left nothing to chance. Following the lead of the Royal Navy in Halifax and other Allied ports, Uncle Sam’s patrol boats installed an anti-submarine net across the Verrazano narrows. This effectively sealed the entrance to New York harbour and provided protection against submarine attacks in a war that became bloodier by the day.

By December 1917, the fighting in Europe was into its fourth calendar year. The carnage had dragged on much longer than Aimé Le Médec—or anyone else—had ever expected or even feared. However, after just six months of involvement, America’s military and industrial muscle were already making themselves felt. Momentum in the war was beginning to tip in the Allies’ favour.

The British and American navies were sinking as many as ten U-boats each month, faster than German shipyards could replace them. Despite this, the threat of submarine attacks in “U-boat alley” remained high for the captains and crews of Allied—and neutral—ships. In December 1917, for example, German torpedoes sent dozens of ships, almost 400,000 tons of cargo, and hundreds of sailors to the bottom of the Atlantic.

Captain Le Médec knew all about the threat posed by German U-boats. He understood, too, that even in ideal sea conditions his ship, which was rusting, in poor repair, and much slower than most merchant ships, was a sitting duck.

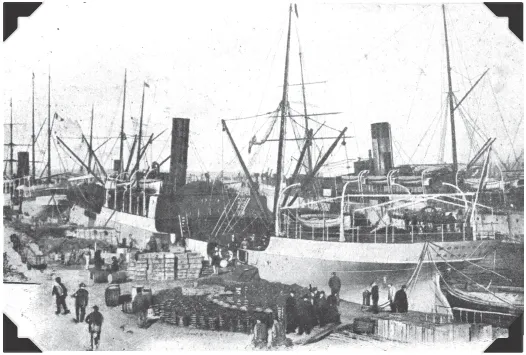

THE MONT-BLANC WAS a typical ocean-going cargo vessel in the early decades of the last century. She was a serviceable 325 feet from bow to stern—slightly longer than an American football field. However, at 3,121 gross tons, she was a minnow compared with the elite passenger liners that plied the waters between Europe and North America. The RMS Olympic, the sister ship of the RMS Titanic, was a prime example.

Three massive propellers powered the Olympic through the waves at a top speed of twenty-one knots—about twenty-five miles per hour. The Mont-Blanc crawled along at a relative snail’s pace. Her three-cylinder, 247-nominal-horsepower “single-screw steam engine” cranked a solitary propeller. Going all out, even when she was shiny new, the ship could only have reached eleven knots—a little under thirteen miles per hour—“in ballast,” as old salts say when describing a ship that is sailing with empty cargo holds.

Launched in June 1899 at the Raylton Dixon & Company shipyards in Middlesbrough, England, the Mont-Blanc was a for-hire “tramper,” a packhorse of the sea that carried goods and passengers for money. Yet she was built “to Lloyd’s [Register] highest class,” a complex set of standards that had as much to do with pegging the level of insurance premiums a ship’s owner paid as they did with the quality of the vessel’s construction.

In her first year afloat, the Mont-Blanc was owned by the Société Générale des Transports Maritimes à Vapeur shipping line. As such, she travelled between Marseille, on France’s Mediterranean coast, and sundry ports of call in Brazil and Argentina. However, owing to the ever-shifting financial tides of maritime commerce, title to the Mont-Blanc passed through various hands. By 1906, the ship had seen too much hard use, hauling bulk shipments of ore. Her centime-pinching French owner was intent only on wringing as much profit as possible from his investment. Thus, he scrimped on upkeep and maintenance, with predictable effect. After just seven years in service, the Mont-Blanc’s glory days were already in her wake. She was old before her time.

THE SS MONT-BLANC IN THE PORT OF MARSEILLE PRIOR TO HER MAIDEN VOYAGE ON SEPTEMBER 23, 1899. (COURTESY OF M. ALAIN CROCE)

IN DECEMBER 1915, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT)—popularly known as “the French Line”—purchased the Mont-Blanc. As the French government’s preferred carrier, CGT ships hauled mail and provided other public services. When the Mont-Blanc joined the CGT fleet, it was a given that she would serve the needs of France. With that in mind, the new owners sent the ship into dry dock for the repairs and updating she needed to ensure her continued seaworthiness. As one observer noted, the Mont-Blanc had been “pushed to the very limits of safety and sea-worthiness.”1

The ship had undergone a facelift, a refit, at Bordeaux in September 1917. Workers there had serviced the engine and carried out other essential upgrades. In addition, the workers had painted the Mont-Blanc a sombre camouflage-grey and had fitted her with two cannons—a 90-mm one on the foredeck, another astern. There was room on deck to store a few shells for each weapon, “ready to be fired in case of necessity,” as Aimé Le Médec noted.2 The rest of the ammunition, 300 rounds, was stowed belowdecks; if the ship’s gunner needed shells, someone ran to fetch them.

Deck guns had become standard additions to Allied merchant ships in World War I. The crews were under orders to shoot it out with any German U-boat that was bold enough to surface before launching its attack; that had happened often in the early months of the war. Not so much by December 1917. Regardless, the Mont-Blanc’s armaments added an element of military muscle to her profile. The weaponry was intended to deter an enemy attack rather than to defend against one.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1914, the CGT fleet had included just twenty-five vessels. When, on July 28, the opening salvos of “the War to End All Wars” shattered the peace in Europe, the French government decreed that henceforth all large French cargo ships were under the direction of the French Admiralty and were subject to military orders. The navy did not commandeer them; instead, it mobilized the officers of the country’s merchant marine, drafting the vessels into the French naval reserve. No ship sails without a master and officers.

CGT captains were told what cargoes their ships would carry, when they would carry them, and to what ports of call. “I was then under the orders of the French government,” said Aimé Le Médec.3

Even after her refit, when carrying a full load of cargo the Mont-Blanc’s top speed was a glacial eight to eight and a half knots. That being so, she had been fortunate to survive the first three years of the war unscathed. However, by late 1917, with the German navy expanding the range and intensity of its U-boat campaign, the chances of a lumbering vessel such as the Mont-Blanc falling victim to a torpedo had increased dramatically. In the autumn of 1917, she had defied the odds yet again to make an incident-free, but nerve-racking, passage from Bordeaux to America. The Mont-Blanc had been carrying just a few crates of machine parts when she arrived in New York City on November 94 after being at sea for three weeks and enduring the bone-numbing cold of the North Atlantic.

As was generally the case when a tramp steamer delivered her load, the captain and crew had no idea where their next assignment would take them or what their ship’s next cargo would be. Such matters were for the shipping company’s local agent to arrange. It was the agent’s job to represent the vessel’s owner in customer dealings. In the case of the CGT line in 1917, the customer was invariably the French military.

In New York City, Captain Le Médec’s orders were to proceed to the CGT’s Hudson River pier, at the foot of West 14th Street. There, he was to take on another small load of machinery parts and then wait for further instructions. The Mont-Blanc’s crew members were fine with that. Once the men had finished their daily tasks, they had some time to explore the streets of New York City and savour the earthy pleasures that sailors on the prowl seek out. Meanwhile, Captain Le Médec could only cool his heels and wonder about his next assignment. When finally he learned what it was, he had cause for concern.

TWICE DURING THE MONT-BLANC’s three-week stay in New York City, Le Médec and Edward Flower, the assistant maritime inspector in the French government’s office and the CGT’s local agent, visited the offices of the British Admiralty. There the two men met with Commander Odiarne Coates, the senior Royal Navy (RN) officer in New York who was the port’s convoy officer. The forty-nine-year-old Coates had retired in 1913 after a twenty-nine-year naval career, but like many other RN veterans, he had returned to duty when the war began.5 It was Coates’ job to see to it that the Mont-Blanc was included in a naval convoy for her return voyage to Bordeaux. Flower served as the interpreter in conversations between Coates and Le Médec, whose grasp of English was iffy at best.

When the commander queried the Frenchman about his ship’s technical specifications and nautical capabilities, Le Médec was chagrinned. “Je ne sais pas,” he said repeatedly. “I don’t know.”

That was true. The voyage from Bordeaux had been his first aboard the Mont-Blanc. After signing on with the CGT in 1906 as a second officer, it had taken him a decade to work his way up to become a captain. Le Médec had persisted. Being just five feet, three inches tall and a shade over 125 pounds, he was used to big challenges, both in the physical environment of the sea and in life. However, whatever the captain lacked in physical stature, he more than made up for with his courage and strength of character.

Back home in France, members of the Le Médec family knew their Aimé as a man of steely determination with a nimble, inquisitive mind. He was detail-oriented and when at sea insisted on doing things “by the book.” At home, he was more relaxed and easygoing. Le Médec collected souvenirs of his voyages to exotic ports of call—a...