![]()

Manitoba Studies in Native History XI

“A National Crime”

The Canadian Government and the

Residential School System, 1879 to 1986

John S. Milloy

The University of Manitoba Press

![]()

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part 1 – Vision: The Circle of Civilized Conditions

1 The Tuition of Thomas Moore

2 The Imperial Heritage, 1830 to 1879

3 The Founding Vision of Residential School Education, 1879 to 1920

Part 2 – Reality: The System at Work, 1879 to 1946

4 “A National Crime”: Building and Managing the System, 1879 to 1946

5 “The Charge of Manslaughter”: Disease and Death, 1879 to 1946

6 “We Are Going to Tell You How We Are Treated”: Food and Clothing, 1879 to 1946

7 The Parenting Presumption: Neglect and Abuse

8 Teaching and Learning, 1879 to 1946

Part 3 – Integration and Guardianship, 1946 to 1986

9 Integration for Closure: 1946 to 1986

10 Persistence: The Struggle for Closure

11 Northern and Arctic Assimilation

12 The Failure of Guardianship: Neglect and Abuse, 1946 to 1986

Epilogue: Beyond Closure, 1992 to 1998

Appendix

Notes

References

Index

![]()

Preface

This book, as does every book, has a history of its own. It has its causes, its passage from research to writing, and therein lies its character. The initial version of this book was a report to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996.

Research on the residential school system was conducted in a number of archives: The National Archives of Canada in Ottawa, the Presbyterian, Anglican, and United Church Archives in Toronto, and the Deschatelets Archives of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in Ottawa. These represent the most significant documentary collections for the history of the school system now open to the public. There are, however, other records in regional, provincial, and diocesan archives, and in private holdings, throughout Canada.

The National Archives files provided federal government records for the years up to approximately the early 1950s. The Department of Indian Affairs provided information on the schools operating after that period. The Department retains a very significant number of files that are still closed to general researchers. The Royal Commission secured access to this documentation only after protracted and difficult negotiations, which, while in the end were successful, delayed the completion of the project. Only one member of the research team was allowed to review the material and then only after signing an agreement setting out a detailed research protocol and obtaining an “enhanced reliability” security clearance.

Work in the Department’s collection was carried out under particular restrictions. In general, all files up to 1993 were made available. However, information that the Department determined fell within the bounds of Solicitor-Client Privilege or Confidences of the Queen’s Privy Council within the last twenty years was not disclosed. All other files, including those carrying access restrictions (Confidential or Protected, for example) were to be made available. Most critically, the Department of Indian Affairs collection was made available only under the provisions of the Privacy Act, which stipulates that no disclosure of personal information, in the meaning of the Act, may be made in a form that could reasonably be expected to identify the individual to whom it relates. The text and endnotes have been amended under the direction of Royal Commission and Department of Indian Affairs lawyers to comply with that stipulation.

Another research restriction that has determined the form and character of this study arose from discussions between the research team and staff at the Commission who were involved in the planning of the project. We decided not to organize an oral history component – that is, we decided not to conduct interviews with former residential school students – because it would have been impossible to provide interviewees with any post-interview support. To have asked former students to reveal their too-often difficult experiences in school and thereafter without being able to offer such support, we felt to be unethical.

![]()

Acknowledgements

This book could not have been completed without the assistance and cooperation of many individuals. I am most grateful to the Commissioners – G. Erasmus, R. Dusssault, J.P. Meekison, V. Robinson, M. Sillett, P. Chartrand, and B. Wilson – for having provided the opportunity to undertake this research and for their determination that no documentary stone be left unturned in a search for information about the school system.

The project researchers – F. McEvoy, S. Heard and I – owe thanks to staff and consultants at the Royal Commission: D. Culhane, M. Castellano, A. Reynolds, N. Schultz, N.-A. Sutton, L. Forbotko, R. Chrisjohn, D. Reaume, all of whom provided generously much-needed support, direction, and invaluable advice. The staff of the Oblate, Anglican, Presbyterian, and United Church Archives, and the National Archives of Canada were most cooperative in identifying sources and making files available. At the Department of Indian Affairs, K. Douglas facilitated research on the closed INAC collection, making a difficult situation manageable and productive; and John Leslie, an expert on the history of the Department, provided advice and direction. Computer, clerical, and editorial assistance were provided by K. Cannon, Managing Editor of the Journal of Canadian Studies; Carol Little at the Trent University History Department; Jessa Chupik-Hall, M.-J. Milloy, and Bridget Glassco.

Special thanks are owed to Professor G. Friesen for his advice on recasting the manuscript, on moving it from report to book, and, in that venture, to the members of the Manitoba Studies in Native History Board and the staff at the University of Manitoba Press, particularly Director, David Carr, and Managing Editor, Carol Dahlstrom.

Finally, I owe a sizeable personal debt to Clare Glassco, Jeremy Milloy, Bridget Glassco, M.-J. Milloy, and Molly Blyth for unstinting support and understanding in what has been, over the last five years, an all-consuming and too-often cheerless project.

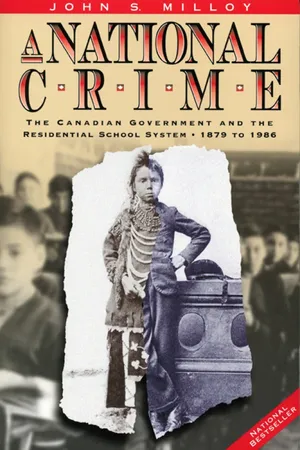

A potential pupil (Anglican Church of Canada,

General Synod Archives, P75-103, S8-21, MSCC)

![]()

Introduction: Suffer the Little Children …

In 1939, the Anglican Church published and circulated to its parishioners a pamphlet celebrating its work in “Indian and Eskimo Residential Schools.” The pamphlet traced the history of the church’s involvement in Aboriginal education from “the origins of these Institutions in Western Canada” thanks to the efforts of the Reverend John West in the Red River Settlement in 1820. From that “small beginning this system of Indian education, under Divine Guidance and help, has gradually developed until we have at the present time nineteen schools of the residential class.” Individual Anglicans, the text continued, as well as “Sunday Schools, Bible Classes, A.Y.P.A.’s [Anglican Young Peoples’ Associations], etc.,” could follow in West’s footsteps; they, too, could “help” if they would “‘adopt’ an Indian boy or girl in one of the Indian Boarding Schools.” Only $30 a child was required. Contributors would “be sent the name of the child, age, school and a photo.”

As an inducement, no doubt, the pamphlet contained a variety of photographs of students and of the schools – each in its own way meant to be an illustration of the care given the children and the fine educational work being done. There were pictures of children dressed in neat, bright uniforms, smiling confidently at the camera, one of a “sewing class … in which the girls [were] taught mending and plain sewing” and another of boys “sacking vegetables” in a field with the accompanying note: “meat, vegetables, butter and eggs are in most cases produced by the Schools for their own use.” There were pictures of happy times – “A Christmas party in one of [the] Residential schools” and of healthful, carefree activities – a “physical education class” and “The Scout Troop … Typical of Troops in many of the Schools.”

There were, of course, pictures of the schools themselves described as “fine, new,” and “modern” – impressive structures seemingly well-maintained. They were “valuable … as centres of education” but also “for the help they [gave] in saving the lives of children who would otherwise perish” if left in their communities marked by disease and pove...