- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

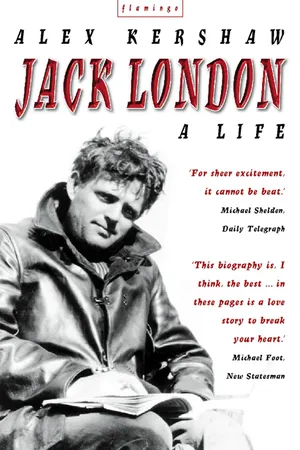

JACK LONDONEPUB ED EB

About this book

A full-blooded, pacy biography of one of the most charismatic writers of the century, whose life and work were to inspire Hemingway, Steinbeck, Kerouac and Mailer. 'We cannot help but read on': TLS. 'The energy, dynamism and sheer bursting life-force of Jack London bowls you over': Scotsman.

- Jack London's life story (1876–1916) is as dramatic as any of the fiction he wrote. Born illegitimate in San Francisco, he was (in his teens) an oyster pirate, seal-hunter, hobo, Klondike goldminer – and spectacular drinker.

- On publication of The Call of the Wild in 1903, he became the most highly publicised writer in the world. Subsequent books, including Martin Eden, White Fang, The Iron Heel, The People of the Abyss, John Barleycorn, The Sea Wolf, continue in print as world classics in many languages.

- Apart from writing 50 books, he lectured for the Socialist Party in America; was a war correspondent in Korea and Mexico; introduced surfing to the West Coast; sailed the seven seas in his yacht, the Snark.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

1

Aloha Hawaii

Somehow, the love of the Islands, like the love of a woman, just happens. One cannot determine in advance to love a particular woman, nor can one so determine to love Hawaii. One sees, and one loves or does not love. With Hawaii it seems always to be love at first sight.

JACK LONDON, ‘My Hawaiian Aloha’

DURING HIS PREVIOUS VISIT to Hawaii, at the height of his fame, Jack had learned to surf, to ride the waves that batter the island’s golden shores. Ten years later, in 1916, the sands in front of his beloved Seaside Hotel have washed away. Razor-sharp coral is all that remains. Now his Pacific paradise soothes neither his body nor his brain.

In pain from his rheumatic joints, Jack begins to shave. Once a ‘blond beast’, with the face and body of a ‘Greek god’, he is not yet forty but feels like an old man: his ankles are swollen, his deep blue eyes are bloodshot and lifeless. Months ago, he stopped exercising – he who once prized his image as the he-man of American letters, who boxed, surfed, fenced and swam to the peak of fitness for so many years. Now it hurts even to look in the mirror. The face that gazes back, ravaged by serious illness, is surely not that of America’s greatest ever literary hero.

Jack sips his fruit juice and begins to pick at his breakfast. The juice is essential for washing out the poisons in his body. Suddenly, he feels sick. He runs to the toilet and vomits. When he returns to the veranda, ghostly white, he lights another cigarette and watches the sun appear from behind the palm trees lining Waikiki Beach.

He can hear the first rumble of traffic passing behind his bungalow; even here, in the middle of the unending Pacific, Ford’s damned automobile has arrived. So this is what his century has brought: rubber tyres and prophylactics and the stink of gasoline. It seems to him now that the world, not just his body, has become old and tired. ‘The world of adventure is almost over now,’ he has recently written. ‘Even the purple ports of the seven seas have passed away, and have become prosaic.’

He turns to the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, the newspaper his Japanese valet, Sekine, leaves by his desk every morning. As he reads about the latest carnage in Flanders’ poppy fields, he is suddenly filled with rage. The mad dog of Europe – Germany – must be stopped. In France, tens of thousands are dying like cattle in the genocide they are already calling the Great War. Had he not predicted the horrors of trench warfare? The maze of mud, stinking of death, awash with the blood of a doomed generation.

His wife is awake. She is walking about the beach-house. Catching her eye, he mouths her a kiss. A few minutes later she is at his side, rubbing his swollen ankles. Can she fetch him anything?

‘I’m all right – don’t bother,’ he says. ‘You’re never up in time to see the huge breakfast I tuck away – three cups of coffee, with heavy cream, two soft-boiled eggs, half a big papaia.’

Jack loosens his royal-blue kimono and moves his chair towards the shade to protect his sickly skin from the sun. He dare not tell her that he throws up his breakfast every morning, nor that he seldom changes out of his bathing trunks and sandals because it takes too much effort to dress.

His wife is calling to him. She still has slim ankles, an innocent face, the snub nose of a small child. ‘Are you going to swim with me today?’ she asks.

‘Yes – I believe I will … No, I’m right in the thick of this new box of reading matter from home. Oh, I don’t know – the water looks so good … But no; I’ll go out in the hammock where I can read and watch you.’

All his life, Jack has looked to books for a philosophy of life, and to take him away from the ‘fever of living’. As an idealistic young man, he read everything he could about the great thinkers of the late nineteenth century: Nietzsche, Darwin and Marx. Now he is immersed in Jung’s seminal Psychology of the Unconscious. He has discovered the most significant of twentieth-century sciences.

Through reading Jung’s earliest writings, Jack is beginning to examine his own life, a story far more dramatic than any of his fifty books which line a shelf in his study. At last, he is studying his addictions and terrors. It is too late for denial.

‘Personality is too vague for any of our vague personalities to grasp,’ he once believed. ‘There are seeming men with the personalities of women. There are plural personalities. There are two-legged human creatures that are neither fish, flesh, nor fowl. We, as personalities, float like fog-wisps through glooms and darknesses and light-flashings. It is all fog and mist, and we are all foggy and misty in the thick of the mystery.’

Now the mists are being blown away. Slowly, Jack is turning his back on the beliefs of his youth, the mistaken philosophies that have damned his life. How naive of him to have thought that knowledge of the external world is all that counts, that the soul is not to be trusted …

Time to write. Time to begin his daily therapy. For twenty years his routine has never altered. Every day a thousand words before lunch, without fail, whether caught in a gale rounding Cape Horn, waiting for cannibals to attack, or lying hungover in bed in an expensive hotel in New York.

Jack picks up a blunt pencil, lights another filterless Russian Imperiale cigarette, one of sixty he smokes a day, and begins to scribble on the envelopes of several letters from his readers. He still receives hundreds each week, many from aspiring writers. He has rarely refused them advice, and still takes great pleasure in helping young men achieve success.

‘I assure you, in reply to your question,’ he writes, ‘that after having come through all of the game of life, and of youth, at my present mature age of thirty-nine years I am firmly and solemnly convinced that the game is worth the candle. I have had a very fortunate life, I have been luckier than many hundreds of millions of men in my generation have been lucky, and, while I have suffered much, I have lived much, seen much, and felt much that has been denied to the average man. Yes, indeed, the game is worth the candle. As a proof of it, my friends all tell me I am getting stout. That, in itself, is the advertisement of spiritual victory.’

Here in Hawaii, Jack feels distant from his past. The cobalt waters seem to wash much of it away. Yet when he turns his eyes to the shade, he still sees images he can never erase: of the frozen Arctic wastes, heavy with the ‘white silence’, where wolves had called his name; of gold nuggets glinting in the half-light; of great fires and storms that destroyed his dreams; of smoke-filled halls and red-flag-waving crowds; of fist-fights in dockside bars and midnight hours spent with twittering Oriental whores.

This afternoon, after he completes his thousand words, perhaps he will play high-stakes poker with the entrepreneurs who have turned Hawaii into a tourist destination for the rich. He used to threaten to string such men up in the streets. Once, he agreed with Karl Marx: ‘Accumulation of wealth … is at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation …’

The sun is unbearably hot. It has wrapped the snow-capped volcanoes in haze. Jack wants to spend this afternoon doing more than lounging in a hammock under a palm tree or marvelling at the genius of Charlie Chaplin in a muggy movie theatre. He aches to feel the soothing, milky waters, to surrender himself to the Pacific, the ocean he tried to master in his youth.

His wife looks concerned. In the distance she sees the heavy surf, yet she follows her husband into the water and towards the ‘smoking curlers’, her forty-five-year-old body still that of a woman ten years younger, supple and slim as ever in her clinging wool bathing suit. Beyond the shallows, through thick wracks of seaweed they crawl, the crashing of the waves on the reef growing louder at every stroke.

‘Keep flat, keep flat,’ Jack commands as the breakers tower above them.

They swim on, past the surf into the calmer, deeper waters, below them strange marine life, coral all the colours of the rainbow. For half an hour they idle in the cobalt-blue ocean. Then Jack begins to sink. His ambition has outreached his strength yet again. He grabs at her, as a drowning man might grab at a piece of flotsam in an empty ocean. She goes under, swallows water, loses her swimming-cap, and then surfaces, blinded by her red hair, gasping for air.

‘Relax,’ she soothes. ‘Make yourself slack – slack in your mind; and your body will slack. Yield. Remember how you taught me to yield to the undertow.’

Mercifully, men on surfboards suddenly appear from behind a wave. In an instant, it seems, they lay Jack on a board, massage his cramped muscles, and then his wife ferries him to the shore.

For a few hours, he manages to hide his humiliation from her. ‘You’re so little,’ he finally says. ‘So frail, little white woman.’

Jack takes hold of her arm. ‘Look at that arm, with its delicate bones,’ he smiles proudly. ‘I could snap it like a clay pipe-stem, and yet your arms never failed in the sea today.’

He points to his head. ‘That’s where it comes from,’ he says. ‘That’s where it resides – that’s what makes the trivial flesh and bone able to do what it does.’

As the sun begins to set, Jack retires for cocktails. There is a long night ahead, and he must fortify himself well in advance. Three years ago he wrote a book, John Barleycorn, which he called his ‘alcoholic memoirs’. To the last page he catalogued a life of heavy drinking and then denied that he was an alcoholic.

But look at him now – feeling like a saint because only a couple of glasses get him jingled. Because his kidneys no longer process the alcohol.

‘Sometimes I think I’m saturated with alcohol, so that my membranes have begun to rebel,’ he says. ‘See! How little in the glass, and this is my first drink today.’

At dinner, against doctors’ orders, he gorges on raw aku, a Pacific fish. Like a ravenous wolf, he adores barely cooked meat: roast duck, lamb chops, tuna steaks. Any still-bloody flesh will do. His favourite midnight snack used to be a ‘cannibal sandwich’: raw beef chopped fine with small onions.

He has always had a great appetite, and can remember writing to his first girlfriend about the hunger he felt as a boy. He was so starved for meat, he claimed, that he stole from lunchboxes at school: ‘Great God, when those youngsters threw chunks of meat on the ground because of surfeit, I could have dragged it from the dirt and eaten it … This meat incident is an epitome of my whole life … Hungry! Hungry! Hungry! From the time I stole meat and knew no call above my belly, to now when the call is higher, it has been hunger, nothing but hunger.’

Jack swallows another chunk of raw fish and begins to rave about Psychology of the Unconscious. His wife listens patiently. She has learned that she must stand by ‘night and day, for his instant need’. For the next few hours, until he burns himself out, she struggles to get a word in edgeways. He is argumentative, and often pushes a point too far before exploding with resentment. Soon, she knows from experience, he will become less bullish, and will begin to rant about his current pet hate: East Coast socialists, the bleeding-heart liberals wearing their social conscience on their starched sleeves, whose beliefs now taste like ashes in his mouth.

A few weeks ago, after a decade as America’s highest-profile revolutionary, Jack resigned from the Socialist Party in disgust. His brothers wouldn’t support his call for America to go to war against the Kaiser. They had no guts. Now they accuse him of betrayal, of going soft. He has become, they sneer, one of the fat capitalists he once despised.

‘Radical!’ Jack snorts, lurching about in his chair. ‘Next time I go to New York, I’m going to live right down in the camp of these people who call themselves radicals. I’m going to tell them a few things, and make their radicalism look like thirty cents in a fog! I’ll show them what radicalism is!’

They think he’s finished. The critics write him off as a hack, a tragic sell-out, the author of a couple of brutal stories about dogs.

‘Just wait!’ he cries. ‘Wait until I’ve got everything going ahead smoothly, and don’t have to consider the wherewithal any more. Then I’m going to write some real books!’

A few drinks later, Jack changes tack again. He loosens his black tie and unbuttons his white silk shirt.

‘My mistake was opening the books,’ he almost whispers. ‘Sometimes, I wish I had never opened the books.’

His wife smiles. One day, she has already resolved, she will tell the world about her husband. His has been the story of ‘a princely ego that struggled for full expression, and realised it only in a small degree’.

It is now pitch black. Late at night, Jack often becomes maudlin and sentimental.

‘You are the only one in the world who could live with me,’ he says. ‘Bear with me. Please. You’re all I’ve got.’

‘I will,’ she soothes. ‘I will.’

After dinner, at 10.30, Jack retires to his sleeping-porch fronting the ocean. He and his wife have slept apart for several years because of her nightly battles with insomnia.

Until 2 a.m., as every night, he reads his mail. Then the quest for a few hours’ peace begins in earnest. To help him through the night he consults his medicine chest, the most important object in his life. It contains an array of pain-killers: strychnine, strontium sulphate, aconite, belladonna, morphine, and that sweetest of all escapes – opium.

‘Oh, have no fear, my dear,’ he reassures his wife whenever he reaches for his stash of narcotics. ‘I’ll never go that way. I want to live a hundred years.’

Jack is now his own anaesthetist. He prescribes himself enough to stop the pain, just as he used to down bottles of whiskey.

He takes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Foreword: The Valley of the Moon

- Part One

- Part Two

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Notes

- Praise

- Books by Jack London

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access JACK LONDONEPUB ED EB by Alex Kershaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.