![]()

1 Introduction

As technological advancements continue at rapid speeds, it is easy to think that everything has changed. Letters are replaced by e-mails, landline telephones are replaced with mobiles and Internet telephony, and print and television news are dinosaurs that somehow continue to limp on despite having gone instinct years ago.

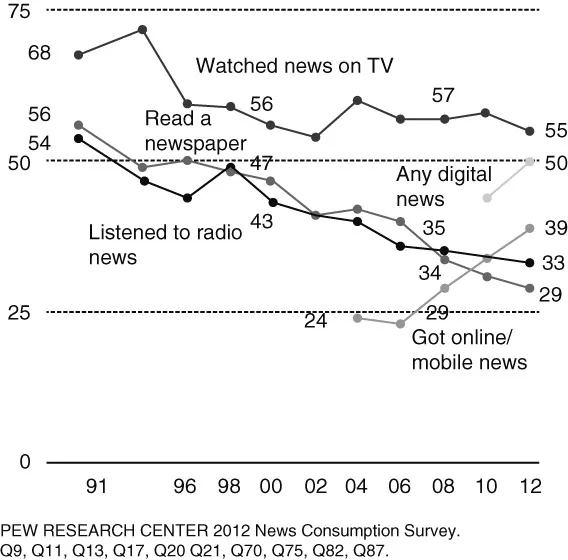

This last point, however, is not borne out by the evidence. Audiences may have declined, they may have aged, and they may also seek additional sources of news, but over the last 20 years, television has continued to be the biggest source of news for Americans. The Pew Research Center compiled data from its “Where People Got News Yesterday” surveys from 1990 onward, which revealed that television news still has the highest percentage of news consumers of any type of news source, as shown in Figure 1.1.1 Television news still matters.

Television reaches a mass audience, beaming moving pictures from around the world into everyone’s living rooms. By 1960, 90 percent of American homes had a television set; 98 percent had televisions by 1978.2 Nielsen reports that in 2009, more than half of American homes had at least three televisions and that, on average, there are more televisions in American homes—2.86 per home—than there are people, 2.5 per home.3 The most recent numbers available show further increase in the reach of television: Nielsen estimates that in 2014, there were 116.3 million homes with at least one television in them and, “that nearly 296 million persons age 2 and older live in these TV homes.”4 Since its spread into American homes, television has become the primary way people get information about the world around them. This level of penetration of the daily lives of citizens combined with the advent of cable, satellite, and digital technology allowing for faster news cycles and 24-hour news channels gave birth to the idea of the CNN Effect. Although it is named for CNN, the 24-hour Cable News Network, and inspired by that network’s round-the-clock coverage of the Persian Gulf War and US military intervention in Somalia, the CNN Effect has been a broad theory: television news coverage, either broadcast or cable, of major issues would force government action, a sort of humanitarian “if they see it, they will come” argument.

Figure 1.1 Where People Got News Yesterday

I began this project as a test of the CNN Effect with the intention of examining the human rights content of television news in the US and UK as a way of determining whether human rights television news coverage could drive human rights policy or the other way around, and whether this would be the same across two different countries with two different media systems. During the long process of collecting and analyzing data, however, it became apparent that there is not very much television coverage of human rights at all in either country. There is, in fact, so little human rights coverage on television news that it is impossible to support the idea of a CNN Effect on human rights issues. The violations, it seems, are not being televised.

In 1970, Gil Scott-Heron recorded “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” a spoken word poem about the numbing power of television, referencing musical acts, political figures, and popular advertising campaigns as a way of pointing out that they are a distraction from the revolution, which will be live. Since then, the phrase has been adapted and remixed in various ways by musicians, filmmakers, and intellectuals to the point that it has become part of popular culture, divorced from Scott-Heron’s original usage. Artists ranging from Public Enemy to Elvis Costello have used the phrase for their own purposes, and this book is titled in the same vein. There is no doubt that there are tremendous human rights violations occurring every day in many places around the world, as well as within the US itself. But these issues are not covered by television news in either the US or the UK—the violations are simply not televised.

That is not to say, however, that this study has not revealed important data. Examining the small amount of human rights content in television news in the US and UK yields insights to what television news producers and policy makers do and do not consider to be human rights, what types of human rights stories get covered, and what, if anything, audiences can learn about human rights from watching television news. Although sources for news abound today, with multiple print, television, and especially Internet outlets available, television news still holds a tremendous market share. Thus discovering what human rights information is conveyed by television is an important task, which is pursued in this study through four different cuts at the television news data.

First, Chapter 2 briefly reviews the relevant communication studies and international relations literatures to build the foundation for the content analyses by defining terms and highlighting the most salient points for comparison between the media and human rights systems in the US and UK. Chapter 3 consists of a content analysis of all of the stories containing the phrase human rights from one US network nightly news broadcast from 1990–2009, which illustrates the amount of human rights coverage in the US in the post-Cold War period and examines both the issues and the countries that are covered in the context of human rights in the US. Objective rankings of human rights conditions throughout the world are analyzed to see what could be getting coverage but is not. Chapter 4 begins the comparative part of this study by analyzing one month of transcripts/shooting scripts for evening news broadcasts in the US and UK in 1990 to see what, if any, kinds of stories might be covering human rights issues without explicitly using the phrase human rights. Comparisons are made to rankings of human rights conditions during that time period as well as to American and British print news to see both what violations are occurring and what print journalists find to be newsworthy. Chapter 5 avoids the potential shortcomings of transcripts and shooting scripts by viewing the actual broadcasts as audiences would have seen them. One week of evening news broadcasts for the US and UK from 1990–2009 are analyzed in conjunction with human rights ranking data to see which stories are covered in each country, how deeply stories are covered, and how that coverage differs from the US to the UK. Chapter 6 takes a case study approach, analyzing all of the television coverage of China, Somalia, and Sudan over time to see what share of each country’s coverage is devoted to human rights. Chapter 7 concludes the study, summarizing the results from the four different television news content analyses and expounding on their implications for media and human rights in the US and UK.

Each of the four different ways of looking at human rights coverage in television news shows a slightly different part of a very small picture, proving definitively that the human rights violations will not be televised.

Notes

![]()

2 Human Rights and the Media in the US & UK

Before examining the human rights content and impact of television media in the US and UK, theoretical lenses, definitions, and local context need to be carefully specified. This chapter will explore the relevant schools of international relations theory: the Constructivists and, more specifically, the theories of NGO action and influence. The meaning of human rights, including its historical and legal origins and possible differentiation from international humanitarian law, is clarified; related terms such as genocide and crimes against humanity are also defined. This chapter also explores the differing contexts of the American and British approaches to human rights. Theories from the field of communications studies and political science are examined to shed light on the concepts of framing, the CNN Effect, and the direction of causality of media influence, followed by a survey of the existing literature on human rights in the media. Finally, the chapter offers a sketch of the broadcasting systems of the US and UK to further contextualize the results of the content analyses that make up the bulk of this study.

International Relations Theory

There is a growing body of literature that is exploring the role of media and communications in international relations both theoretically and empirically. The non-state constructivists focus on the actions, norms, and values of states and non-state actors. The evolution of a norm begins with norm entrepreneurs convincing states to abide by a specific norm, and as states do so, a cascade occurs, where an evolving norm becomes an established norm, the expected and appropriate behavior for all states (Finnemore & Sikkink 1998). Thomas Risse (2000) uses the example of public human rights commitments made by human rights–violating states who, nevertheless, wish to appear to be playing by the rules of civilized states. This leads to the self-entrapment of the state in those commitments, which empowers domestic resistance, transnational advocacy networks, and NGOs to achieve changes in state action.

Norm entrepreneurs cannot influence states qua states but must seek to convince the individuals who comprise those states, either as bureaucrats, elected representatives, or citizens who will subsequently pressure their governments; additionally, norm entrepreneurs themselves are either individuals or groups, networks, or organizations that consist of individuals (Florini 1996). It is therefore important to empirically examine the processes by which individuals are influenced, with one such process being the news media. Jeffrey T. Checkel (1997) argues that in some political systems, such as liberal and corporatist systems, society can wholly or partially constrain state options to drive state behavior in the direction of adopting international norms. Analyzing media coverage of immigration issues in German newspapers, Checkel finds some support for claims of its influence.

More recent work has sought to acknowledge the complex interrelationships between states, non-state actors, and flows of information. Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle’s (2014) work on strategic narratives adapts international relations theories to the real world, where information and communication are real forms of power with real effects. Monroe Price explores the essential role media flows have in shaping international affairs (2002) and the way states are influenced by information as well as the way they seek to control that information (2015).

Social Movements, NGOs, and the Outside Strategy

Social movements and NGOs have also been explored both theoretically and empirically. Keck and Sikkink (1998) map out the relationships between individuals and domestic NGOs in developed and underdeveloped countries, as well as the transnational actors, conferences, and technologies that help bring them together into transnational advocacy groups. Media coverage is a vital part of the information and symbolic politics that network activists use. The authors describe the boomerang process, whereby third-world actors (NGOs, groups, or individuals) provide facts and/or testimony to more powerful first-world allies, who in turn exchange their greater financial, media, and political resources for the information and the international credibility of working directly with the third-world groups. First world and international actors (state officials, NGOs, groups, or individuals) may advocate for change in the original state’s policies or for their own government to pressure the original state. NGOs need to be able to “mobilize their own members and affect public opinion via the media” (23) by “cultivat[ing] a reputation for credibility with the press, and packag[ing] their information in a timely and dramatic way to draw press attention” (22). Snow et al. (1986) argue that social movement organizations (SMOs) perform interpretive actions in constructing, maintaining, and aligning frames or interpretive schema to create meaning. Moreover, they contend that these actions are so vital, those SMOs that cannot frame effectively will cease to exist.

Most social movements, transnational actors, and NGOs seek to change government policy, either their national government’s or another state’s. To that end, they pursue strategies that can be loosely classified into two categories: inside strategies of directly trying to influence policy makers, such as lobbying, and outside strategies of protest politics or attempting to influence the public, which then pressures policy makers. Ruud Koopmans (2004) argues that social movements are now less dependent on direct confrontations with polic...