![]()

1

Conceptualizing democratic consolidation in Turkey

Cengiz Erişen and Paul Kubicek

Democracy is an attribute of states, but the interconnected elements of democracy affect all citizens and groups within a state, interactions among them, and the processes and outcomes of policy-making. Above all else, democracy suggests that the interests and voices of citizens matter. In most conceptualizations of democracy, individuals enjoy expansive rights that empower them and help constrain state power. In its fullest and most ideal form, democracy helps individuals utilize their freedoms and lead more fulfilling, happy lives (Dahl 2000).

This book explores the understanding and practice of democracy in Turkey. Our aim is to unpack the manifold aspects of democracy that affect Turkish citizens and political actors. To that end, we examine the extent of democratic consolidation in various domains, what Wolfgang Merkel (2004) has labeled the “partial regimes” of democracy. The overall goal of the project is not merely to catalog or describe democracy in contemporary Turkey but to employ theories and perspectives both to understand and analyze a dynamic political environment.

We believe this is a relevant and timely scholarly endeavor. First, Turkey is a rising power in a difficult region. Fueled in part by a growing economy as well as ambitious leadership, Turkey in the early years of the twenty-first century has gained an enhanced profile in world affairs. Turkey, of course, has a long history as an important ally of the USA and is aspiring to join the European Union (EU). It is also an important partner for Russia, and has asserted itself, in both political and economic arenas, in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the post-Soviet space. What happens in Turkey matters both to the region and to major players in world affairs. A stable and democratically successful country could even act as a model for neighboring states.

Second, Turkey is an evolving country, one whose democracy is still, in many ways, a work in progress. Turkey has formally been democratic since the introduction of multiparty elections in 1946, and democracy has been periodically interrupted by military intervention. Turkey’s most recent re-democratization dates from the early 1980s, and since then numerous reforms have helped buttress democratic institutions and practices. This, however, has not been a linear or consistent process. There have been ups and downs, accomplishments as well as setbacks. The first years of government under the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi [AKP, or AK Party]) in the early 2000s rank as one of the most dynamic and successful periods in terms of democratic reform. Spurred in part by the prospect of joining the EU, the AKP pushed through measures to expand freedoms of expression and organization, grant rights to the Kurdish minority, curtail the political power of the military, and end human rights abuses such as torture. Civil society also became more active. However, in the 2010s the AKP government has been accused of becoming increasingly authoritarian. This has been evidenced most clearly in the crack-down on media and on protests – the Gezi Park demonstrations in 2013 rank as the largest and best known – but extends into other realms as well, including commitment to rule of law and minority rights. Political polarization is pronounced. Beyond the formal political arena, democracy remains challenged by other factors, including struggles for gender equality and a growing gap between the rich and the poor. Several commentators, including some contributors to this volume, have even raised the question of whether the problems in Turkey have grown so acute that it may make more sense to reconsider whether Turkey meets the general criteria to be regarded as democratic.

Third, Turkey has unique importance as the Muslim country with the most extensive experience with democracy. The notion of Turkey as a “role model” for other Muslim states, particularly given its secular and democratic system, has often been invoked by academics and policymakers (Karpat 1959: x, xi; Lewis 1987: xi; Toprak 2005). What is emphasized in that model, however, has varied over time. Under the AKP, a self-described “conservative democratic” party that has roots in earlier Islamist parties, there has been discernible movement away from the assertive secularism of the Kemalist model and toward an approach that allows for a greater role of religion in the public sphere. For example, the vexed headscarf issue – bans on which became one of the most polarizing issues in Turkey – was solved in a manner that granted pious Muslims greater freedom. Scholars have noted the movement away from authoritarian, state-imposed secularism and the rise of a “post-secular society” (Göle 2012). For some, this is the evidence to show that Turkey stands as a good example as a “Muslim democracy” led by a “post-Islamist” party (Nasr 2005; Dağı 2006). Others, however, remain wary of the AKP’s allegedly religious agenda. Critics of the government also bemoan its increasingly oppressive policies in certain domains of politics such as media and freedom of speech. Still others note the continued difficulties faced by ethnic (e.g., Kurdish) and sectarian (e.g., Alevi) minorities. All these factors together question the validity of the argument that Turkey could be a model for the region (Kubicek 2013).

Fourth, despite Turkey’s lengthy and dynamic democratic record, it is largely absent in most of the leading scholarly literature on democratization. Most of the comparative work is regionally focused, but because Turkey does not fit neatly into a democratizing region (e.g., Latin America, post-communist Europe, Africa), it rarely features in such work.1 While there are, to be sure, numerous country-level studies of Turkey, many are primarily descriptive and focus on one particular domain or policy area (e.g., the Kurdish question, party development, the role of religion, relations with the EU, foreign policy). These studies often present historical observations of events that could benefit from more rigorous, theory-driven analysis and empirical examination. To that end, in this study we endeavor to cover a broad range of topics and their association with democracy. At the same time, while we do not develop or advance a single grand theory to account for developments in Turkey, we aim to utilize various theories with respect to democratization and advance a theory-informed common framework to orient our study. Indeed, one objective is to have our contributors, notable scholars expert in the various domains of democracy examined in each chapter, introduce theoretical perspectives that they believe best contribute to understanding the topic at hand. While not, in a strict social science manner, a test of competing theories, we believe this approach will allow us to assess the value of different theories and approaches to the multi-faceted issue of democratic consolidation in Turkey.

Finally, the above-mentioned debates about Turkish democracy offer an opportunity to reflect, in a rigorous manner, upon the very notion of democratic consolidation. Despite various shortcomings – which will be analyzed throughout this volume – Turkey remains democratic in the most limited and formal sense insofar as political leadership is determined and held accountable by the vote of the people in competitive elections. The AKP’s power, although troubling to some, is a reflection of its popularity, even as its leading figure, President (formerly Prime Minister) Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, remains a source of polarization. Although the AKP’s rivals are handicapped in various ways, there is both opposition to the AKP – at times quite vociferous – and specific criticism of Erdogan’s actions and policies. No political actor has been able to successfully challenge the legitimacy of having elections determine who should wield political power. In this respect, democracy has become the “only game in town,” which Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan (1996: 5) posited as the hallmark of a consolidated democracy.

However, whether Turkey has a well-functioning democracy is another question, and it hinges on what one means by democracy. While acknowledging that Turkey meets the criteria of what might be called a minimal or electoral democracy whose main attribute is the holding of competitive, multiparty elections, this volume adopts a more holistic understanding of democracy. This is grounded on the idea that democracy is more than just an electoral system; a successful democracy is manifested in several arenas (Linz and Stepan 1996) and/or embedded in interdependent partial regimes and external conditions (Merkel 2004). These components have attitudinal, behavioral, institutional, and constitutional elements and may be considered at the micro and macro levels. At the micro level, we refer primarily to factors formed and operating at the individual level. These include political values, political behavior, identity, orientation toward religion, media influence on citizenry, and public opinion on governmental performance and policies. At the macro level, we refer, inter alia, to overarching conceptualizations of democracy by political elites, the institutional settings that relate to political parties, constraints on the executive, and how the broader socio-economic context affects political development. By analyzing these factors, which will be developed more below, one can begin to unpack the concept of democracy and democratic consolidation and obtain a fuller, more nuanced view of democracy’s fault lines. In this way, our work seeks to address an additional research question – one that could be asked in a number of settings2 – namely why there is a gap between formally democratic rules on the one hand, and, on the other, practices and outcomes that are found wanting by many conceptualizations of democracy.

Democracy as a series of embedded regimes

Of all the concepts in political science, democracy may be the most dissected and modified. David Collier and Steven Levitsky (1997) famously counted over 500 adjectives that have been used to describe it, and our goal is not to add to this number. Seeking to employ a useful framework that allows one to overcome the fallacy of electoralism (Karl 1990) in minimalist definitions while at the same time avoiding maximal definitions that focus on slippery concepts such as social justice, we borrow from Wolfgang Merkel (2004, 2014) and his notion of “embedded democracy.” We believe this concept has great utility, as it both breaks down democracy into a series of operationalizable, discrete, yet interrelated elements while preserving it as a single, holistic system that can be studied in all its complexities. This perspective, one should note, is well grounded in democratic theory, borrowing from literatures emphasizing various prerequisites for democracy such as socio-economic development and broad agreement on the contours of the nation and the development of an effective state (Lipset 1959; Rustow 1970; Boix and Stokes 2003), those that focus more on institutional design and elite bargaining (Schmitter et al. 1986; North 1990; Higley and Gunther 1992; Linz and Stepan 1996; Weingast 1997), those that emphasize supportive elements such as a “civic” or democratically oriented political culture (Almond and Verba 1963; Inglehart and Welzel 2005), and those that stress the role of economic institutions and rule of law (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). Merkel’s refined conceptualization of democracy is also very similar to those employed by other scholars whose works have been seminal in the literature on democratization (Dahl 1971; Barber 1984; Schmitter and Karl 1991; Linz and Stepan 1996; Diamond 1996).

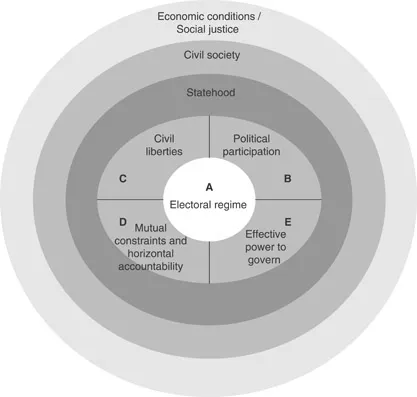

In brief, Merkel’s notion of embedded democracy rests on the claim that in order for a democratic electoral system to function properly – in other words, for there to be competitive elections whose winners both reflect popular preferences and peacefully assume political power – other behavioral, institutional, and structural elements must be in place. Merkel labels each of these supporting elements, as well as the electoral system itself, a “partial regime” of democracy. These are labeled A–E in Figure 1.1. For Merkel, there is an “equiprimordiality” and “inseparability” of civil and political rights as well as the need for institutions to check power and uphold rule of law (Merkel 2014). Thus, while the electoral regime remains the center of a well-functioning democracy, it is nested

Figure 1.1 The concept of “embedded democracy” (source: Merkel (2014)).

within other elements which ensure it functions well. These are: (1) a system that secures political participation and rights, including rights to organization and expression, which are, among other factors, manifested in the development of various political parties and politically oriented groups and movements that allow citizens to exercise these rights as well as a free media that allows multiple political viewpoints to be expressed and disseminated in society; (2) strong support for civil liberties, including a host of rights (e.g., freedom from unjust detention, surveillance, and property seizures) that limit the power of the state and safeguard exercise of political rights; (3) mutual constraints and horizontal accountability, including constitutional provisions for the separation of powers, judicial independence, and rule of law; and (4) effective power to govern, meaning only those officials and institutions which are duly elected by voters or selected through constitutional means (e.g., legally appointed judges) to exercise meaningful political authority, and no other group (e.g., the military, an oligarchy) has reserved powers or a veto on policy. Finally, beyond formal institutional arrangements, these five partial regimes are in turn nested in supportive external conditions, what could also be called prerequisites, including effective state capacity to maintain order and implement policy,3 a vibrant civil society committed to democratic principles (including tolerance of competing groups and rejection of the use of violence to achieve political aims), and sufficient socio-economic development to provide resources (e.g., material, intellectual) to citizens to buttress democratic institutions.4

These concepts, to be sure, reflect an ideal type of democracy; few (if any) states would have a perfectly consolidated democracy by these standards. In this respect, all democracies – not just Turkey’s – are works in progress, although, to be sure, there is no teleology that directs countries continually toward greater democracy. These concepts also reflect what many would call liberal democracy,5 and may be opposed by other conceptualizations (e.g., majoritarian democracy) that de-emphasize expansive rights for citizens and the need for checks on elected officials who have won the support of the majority of citizens. This distinction in the Turkish case will be explored in Chapter 6 by Paul Kubicek.

Significantly, Merkel suggests that all these components are complementary and interdependent, meaning that deficiencies (or improvements) in one sphere will spill over into the others. Thus, while Merkel’s framework does not explicitly elucidate processes of democratization from start to finish, one can use his model not only to describe a regime at a given moment in time but also to assess some of its dynamics. Indeed, Merkel’s framework provides a theoretically informed means to assess how a crisis or problem within a given partial regime or condition can produce a broader fault line that runs throughout the entire democratic system. It is to this issue that we now turn.

Fault lines of democracy

We have mentioned that it would be difficult to argue that any democratic system is fully “embedded” or consolidated in the sense that there are no cracks in its edifice or deeper interior. Numerous threats to democracy can emerge, either by weakening elements of a fairly well-entrenched democratic system or by presenting a formidable obstacle to democratic consolidation in a democratizing state. One can use the notion of embedded democracy to assess systematically from where these threats may emerge and which regime or condition they predominant...