![]()

PART I

An Issei-Nisei Family

PART I INTRODUCES THE HIRABAYASHI FAMILY, TRACING ITS roots back to Nagano prefecture, northeast of Tokyo. As compilers of the book, we have drawn freely from Gordon's personal correspondence and a number of his published and unpublished papers covering his parents' background and his own upbringing, as well as from interviews and conversations that he had with Roger Daniels, Jeanne Sakata, Paul Tsuneishi, Tom Ikeda, and Jim Hirabayashi.

Quotes from Shungo Hirabayashi are from an extensive oral history that Jim Hirabayashi took with his father in 1971.

Religion and spirituality make up a key theme in Gordon's upbringing and youth. What is most interesting in this regard is the way that his parents' participation in Mukyōkai, a Christian sect, laid the foundations for his own spiritual beliefs, which he began to explore seriously on his own when he went off to college at the University of Washington (UW), where he became a Quaker. In this sense, it is no accident that Uchimura Kanzo, the founder of Mukyōkai, noted his strong sympathies toward the Quakers he met when he studied Christianity in the United States.

Beyond this, readers will see that while Japanese language and values were an integral part of Gordon's upbringing, so were elementary and secondary school and all-American activities such as the Boy Scouts. It was in the Scouts, incidentally, that Gordon had his first real brush with race and racialization, at the tender age of eleven. Experiences along these lines enabled him to be surprisingly mature when he faced discrimination at the university level and found his mentors caught between their ideals and the racial color line they adhered to in their daily lives.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Hotaka to Seattle

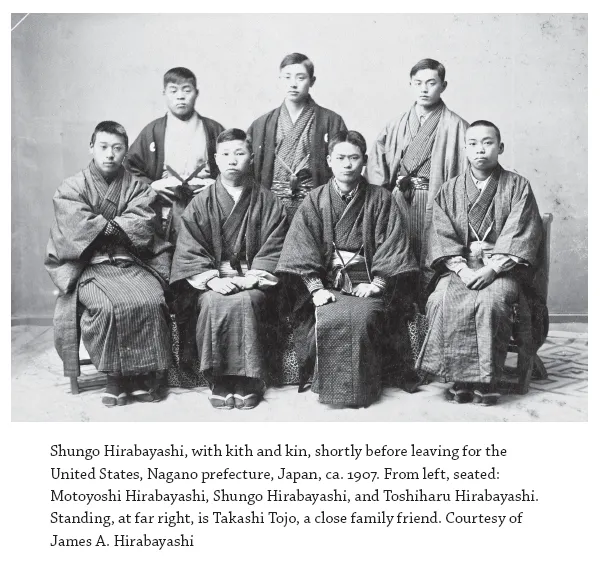

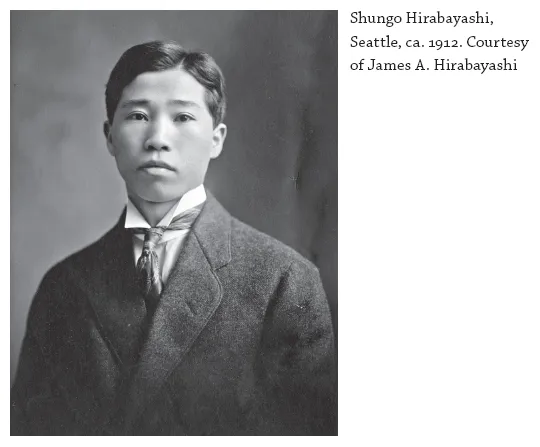

MY DAD, SHUNGO, CAME FROM HOTAKA, A TOWN IN THE FOOTHILLS of the Japanese Alps in Nagano prefecture. There was a neighborhood of a dozen Hirabayashi households in a rural setting at the edge of town. He was the eldest son in one of the Hirabayashi households. His father was a clerk in the town office, and his mother tended what was left of their farm, a few small rice paddies. It was the beginning of the twentieth century, and it was hard times for the peasantry. In order to underwrite industrialization, as Japan began competing with the colonizing Western powers, the Meiji government imposed heavy taxes on farms and other property. Even as a teenager, Dad wondered about his future: “My prospects are not good.”

With the military victories in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, the prestige of the samurai tradition was transferred onto the modern military forces. Dad was inspired by this militaristic spirit:

Among the youth everyone wanted to join the army, and I went to the village office to enlist, but I was told that I was not old enough and was rejected. Wondering what I should do, I heard about a man who went to America and made a fortune in five years. Then came the recruiters for overseas work, and they said, “If you want to go to America, learn English and Christianity.” Before hearing about America, I did not want to go there because Christianity was associated with America, and I was against foreign religions. I had even gone once with my school friends to harass the missionaries who had come to evangelize in the neighboring town.

I wanted to go to America, so I went to the house of Iguchi Kikenji, principal of Kensei Academy, to hear him speak. He talked about the Scriptures, “Christianity is to love people. Love other people as you love yourself. If you are hit on the right cheek, turn your left cheek.” Principal Iguchi argued that violence and war were not the solution to conflict. I was convinced—if Christianity is this way, it is very good.

Iguchi was a disciple of Uchimura Kanzo, the founder of Mukyōkai, a non-church Christian sect in Japan, an unusual Japanese religious denomination. Uchimura had enrolled at the newly established Sapporo Agricultural College in 1877. William Clark, president of Massachusetts Agricultural College, arrived in 1876 to help set up the college. While there, he formed a group, Believers in Jesus Christ, that included all of the first-year students. Uchimura enrolled in 1877 and, pressured by his cohort, joined the student Christian group too.

Uchimura traveled to America in 1884 and visited the Quakers in Pennsylvania who had contributed to his theological perspectives in Japan. He said of Quaker Mary Morris: “I was conscious that she was a partner in my Christian works. She often told me that ‘thee is almost a Quaker theeself.’ I was always sorry that I was ‘almost’ and not ‘entirely.’ Still…my critics recognized in me a strong Quaker influence, and that influence was Mary Morris of Overbrook, Philadelphia.” Uchimura then attended Amherst College in Massachusetts and came under the influence of President Julius H. Seelye: “He opened my eyes to the evangelical truth in Christianity,” he said.

After a semester at Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut, Uchimura returned to Japan in 1888. Reacting negatively to the materialistic orientation of Western Christianity, Uchimura rejected the rituals, priestly hierarchy, dogmas, and liturgy of the traditional Christian church. Instead, he emphasized a personal experience with God and a morality based on truth, hard work, and responsibility to others. On this basis, Uchimura founded Mukyōkai, the non-church Christian movement, by establishing small intimate fellowships where the members shared the responsibility of exercising their faith.

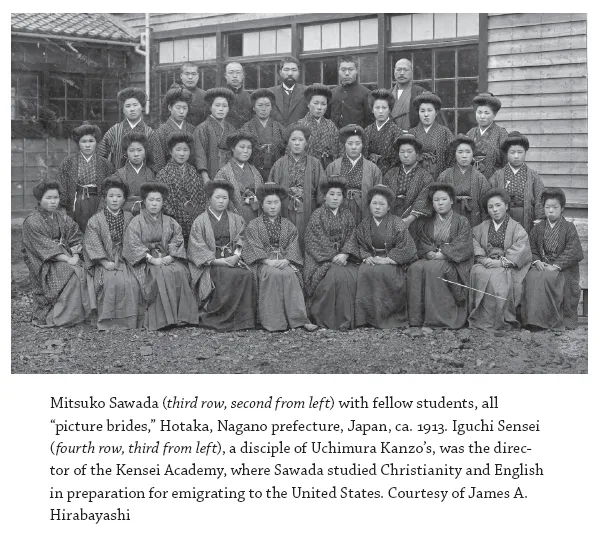

Iguchi, a disciple of Uchimura's, established Kensei Academy in 1898 in Nagano prefecture. The curriculum included Bible study, English, ethics, Chinese language, Confucius, Mencius, and public policy. Boys and girls were not segregated but taught in one room. There was a synthesis of the genuine spiritual traditions of Japan with the Christian gospel as interpreted in the Puritan manner for the betterment of society. Although the government encouraged immigration by urging the young to go to another country to earn money and come back, Iguchi encouraged his students differently. “Have good ambition. Don't go to USA just to make money. Do not be a slave to materialism but go there to build God's kingdom. Live a courageous life. Be a good citizen. Christianity is to love people—love other people as you love yourself. If you strongly have that spirit, there will be no trouble in this world.”

Dad, responding to this very positively, said, “I thought that if Christianity is this way, it is very good. I became convinced, and my heart was changed. With this Christian spirit I came to America, and I have kept that faith all my life.”

SHINKOKYO: THE NEW HOMELAND

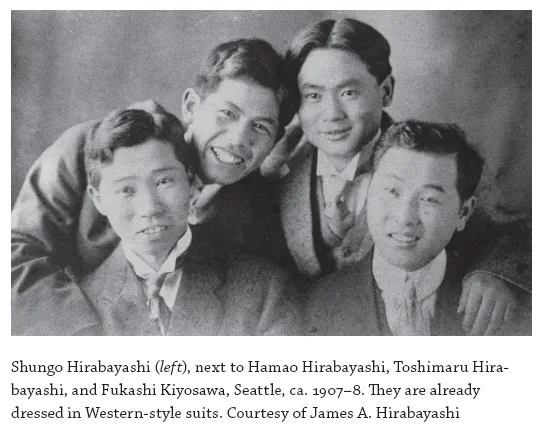

My dad and his Issei associates were mostly young single males from the rural peasantry, the majority of whom had at least an elementary school education. They came as dekasegi, temporary migrants, with the intention of returning to Japan in a few years—rich! This aspiration shifted as gold was not found on the streets. The Gentlemen's Agreement, 1907–8, curtailed Japanese migration to America. Only families of the Issei were allowed to migrate, which led to the development of the “picture bride” custom. The Issei sent for wives and established families, and communities emerged as they began their process of integrating into American society.

Confronted with legal restrictions and general racism, the strong sense of group and communality sustained social protection for the Issei. The tendency toward self-effacement and deference generally was misunderstood by Westerners, who felt that if the Issei thought so little of themselves, they were unworthy of respect. In other circumstances, misunderstanding had produced stereotypes of Japanese as being “sly, inscrutable, untrustworthy, and suspicious.” Two major anti-Japanese arguments were that they presented a “threat against the standard of living” and they were “unassimilable.” That they were not from upper-class origins in Japan may have made it easier for the Issei to accept race discrimination and low status with a measure of fatalism. Japanese traits, in other words, facilitated knowing one's place, doing what is expected, and having the perseverance to survive. In this sense, defense mechanisms for coping with second-class treatment were an Issei adaptive characteristic on the U.S. mainland.

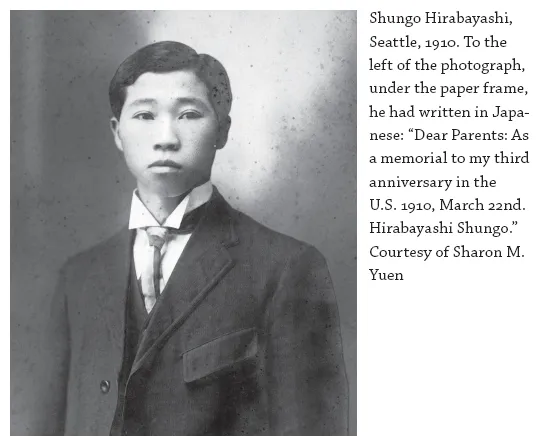

Dad left Japan from Yokohama in 1907.

My dream to go to America came true. Five of us cousins left our families and neighborhood and migrated to America. Initially, we got jobs on the railroad—two teams of four on a handcar. Almost a year later, one of the fellows wanted to run up ahead to see if trains were coming. He jumped off in front of the handcar and was run over. The car cut him in half. After that, none of us went back to work on the railroad. We all took various jobs in Seattle.

A Mukyōkai fellowship group was formed as soon as they settled, and Iguchi Sensei sent many letters and Christian magazines and materials to his former students from Kensei Academy. The Issei from the same town formed the Hotaka Club in Seattle. They also belonged to the Nagano Prefectural Association, a social and mutual aid group, as well as the Nihonjinkai, or Japanese Association, which included all Issei in the Seattle area.

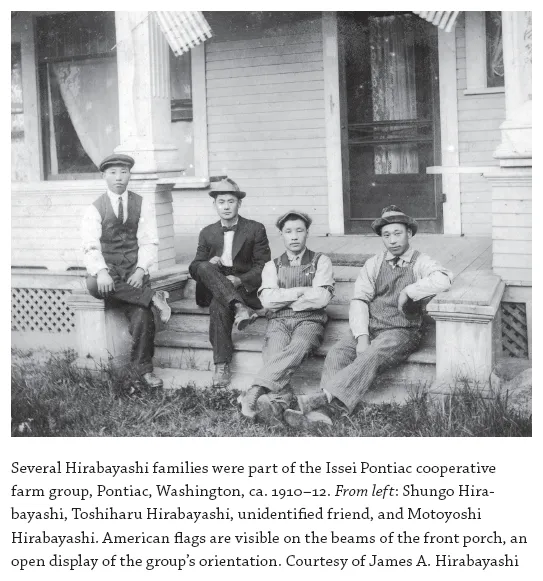

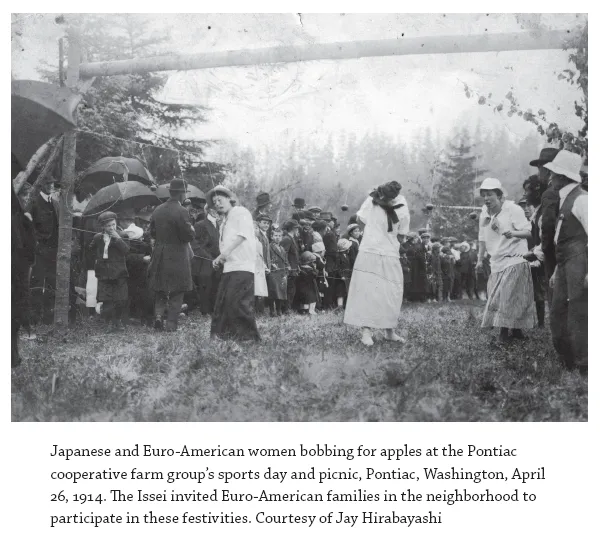

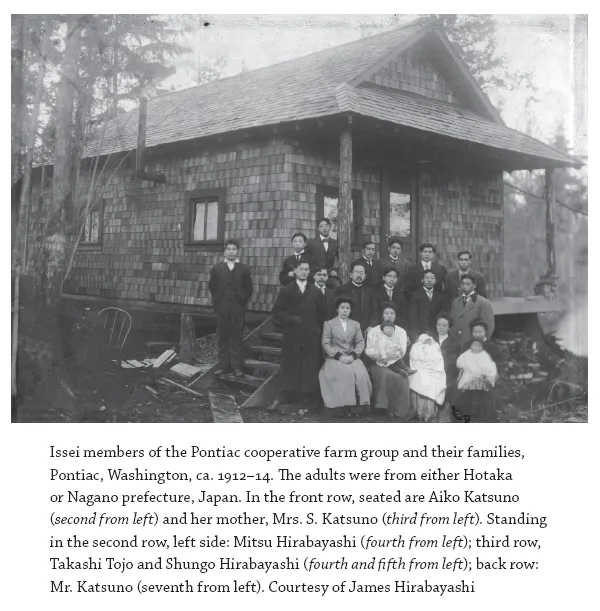

In 1911, several cousins of Dad's, along with friends from Nagano prefecture, formed a collective and began a vegetable garden in Pontiac, on the shore of Lake Washington. Later, this area became part of the Sand Point Naval Air Base. After they brought the harvest in, they hauled vegetables by horse and wagon to the Pike Place Market on the Seattle waterfront. They sponsored picnic gatherings, with food and games, and even invited Caucasian acquaintances who lived in the area to join them. Dad thought of starting a family.

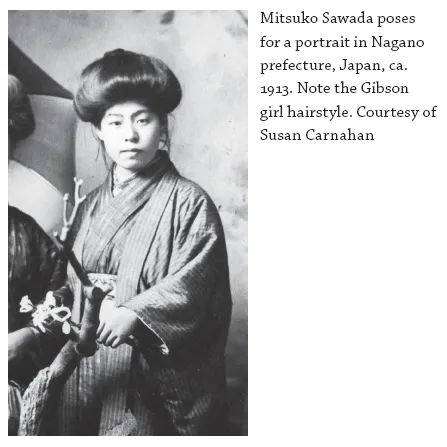

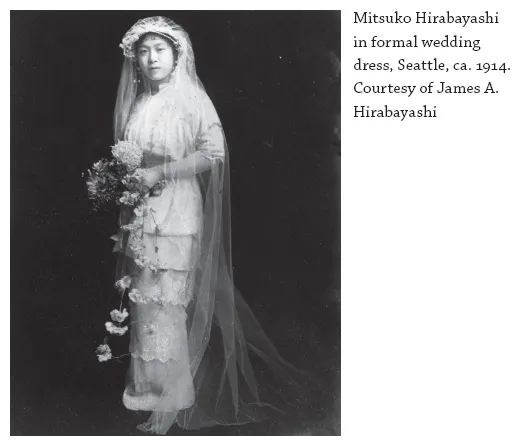

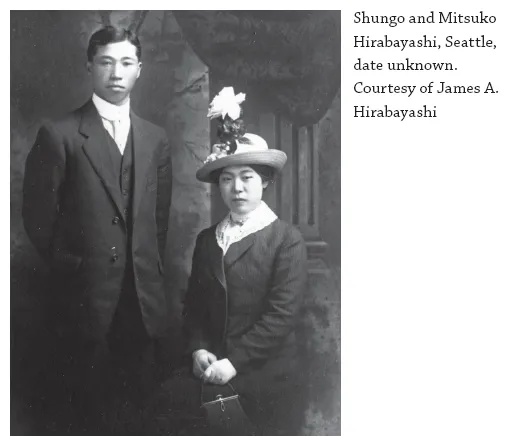

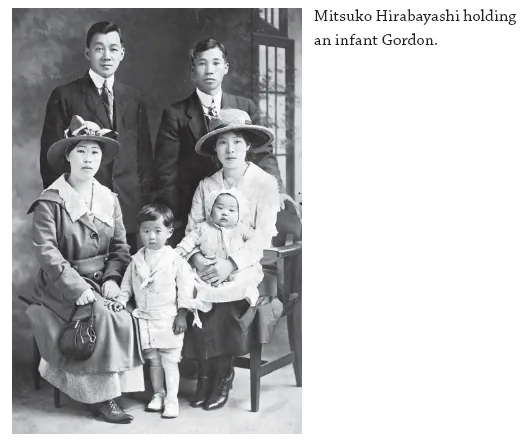

I did not go back to Japan to find a wife but searched for my future wife through my relatives. I trusted everything to my parents. After the families made the arrangements, Mitsu went over to my parents' home, attended Kensei Academy to learn English, and then came to join me in 1914. My family found a real good match for me, so I made a commitment to marry Suzawa Mitsuko. I feel filled with hope for my bright future. We registered as husband and wife in Hotaka, and the following year Mitsu landed in the USA. We had a marriage ceremony in Seattle.

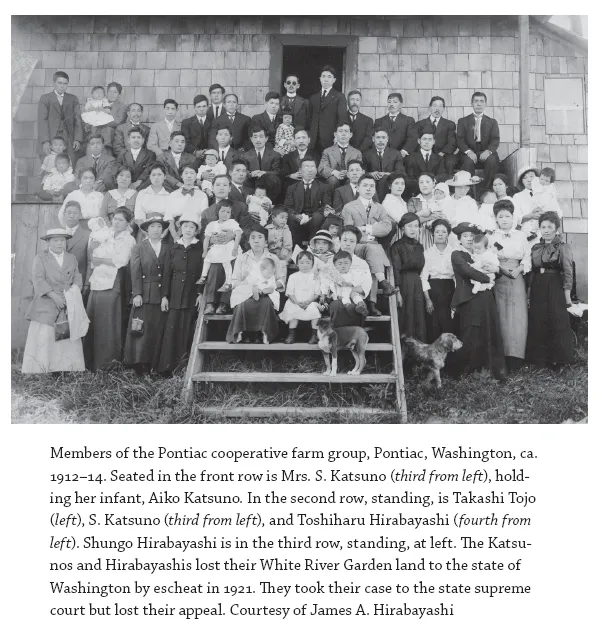

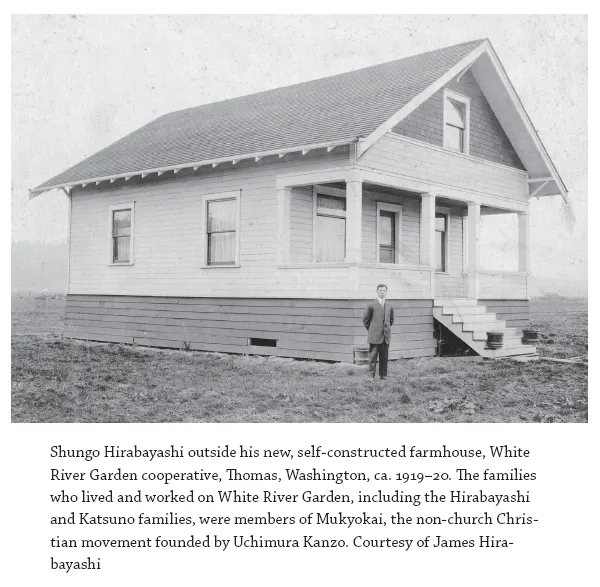

In 1919, four families of the Pontiac collective, including two Hirabayashi families—my father's family and the Toshiharu Hirabayashi family—moved to Thomas, Washington, a rural community twenty miles south of Seattle. These families formed a Christian cooperative, White River Garden, and purchased forty acres of land. Then the difficult development process began: clearing the land of stumps, digging ditches for better drainage, fertilizing the soil, cultivating, and building their homes.

In the early 1920s, John Isao Nishinoiri, a graduate student from Japan, was engaged in field research on Japanese farms on the outskirts of Seattle for his master's degree in sociology at the University of Washington. Nishinoiri wrote:

About five miles south of Kent on the west road leading to Auburn stand four neatly painted houses—this is the White River Garden—they came from the same district in Japan, Azumi in Nagano prefecture. Although four different families live there, they plant, crop, buy, and sell together. Machinery, tools, barns, horses, and all equipment are owned and used in common. Cooperation is not a theory with them; it is a daily practice. This occupational cooperation finds its source in their spiritual cooperation acquired in Japan under the influence of a non-denominational evangelist…[and] binds them together closely.

In spite of the overwhelming materialism of modern American civilization, they maintain their simple Christian faith in its Puritan form. They do not work on Sunday, even in the busiest seasons, and never fail to meet for the purpose of worshipping God. They have no minister, so each of them speaks in turn of his thoughts and experiences. Their simple service is opened and closed with hymns and prayer, and when I attended I felt as if I were sitting with the Puritans of the colonial period.

In Washington State, the 1923 Alien Land Law prevented non-citizens from owning land. Before 1952, immigrant Issei were ineligible for naturalization, so the White River Garden property was purchased in the name of the oldest Nisei in our group, Aiko Katsuno, who was then ten years old. Since she was a minor, they appointed Mrs. Nora Murphy, the wife of Rev. U. G. Murphy, a former missionary in Japan, as her legal guardian. Once the government officials found out about this arrangement, the state of Washington filed suit against White River Garden Corporation, even though it was properly registered in a citizen's name. Government lawyers claimed that the purchase of White River Garden was a deceit and a subterfuge insofar as the real owners of the property were the alien parents.

Unlike others facing similar charges, the Katsunos and Hirabayashis, who developed White River Garden, fought the state and appealed their case to the state supreme court. We lost at each stage, until finally the White River Garden land was taken by the state of Washington. Our families were forced to lease the fields they had formerly owned from the state, in order to continue farming there!

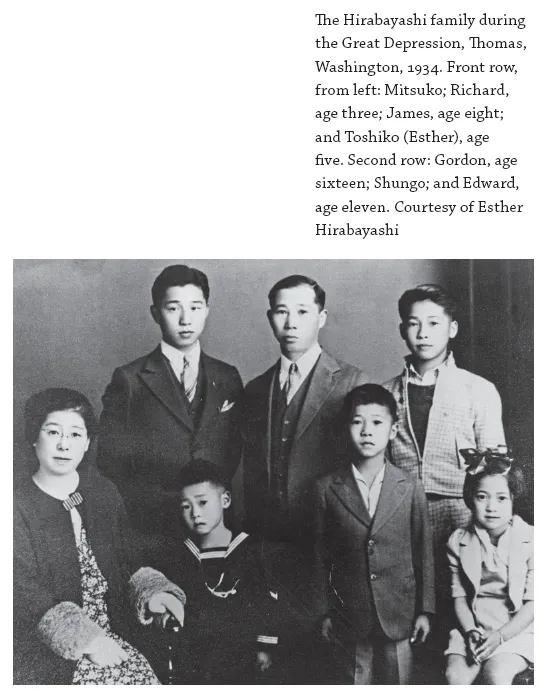

I was a young child then and did not know what was going on, except remembering concerned looks and worries during the komban saiban no sodankai, or evening discussion meetings, on the progress of the court case. There were many late nights like that, which followed a full day's work in the field. There was something that gave strength and meaning to the Mukyokai cooperative members. Their collective belief in the justice of their cause motivated them to confront the state in fighting for what they felt was right. It was also a reflection of the faith they had in God and the genuine fellowship they enjoyed as a group. Something of the spirit demonstrated in their day-to-day living was like a seed in my developing personality and character. The model that these Christian pioneers demonstrated for me must surely have been the source of strength and the guiding light that helped me to confront the government at the time of World War II.

2323__per...