![]()

CHAPTER 1

Christianity, Gender, and Literacy in Northeast China

This is a book about dialogue between and within categories that are constructed as dichotomies: Christian and nonbeliever, missionary and convert, foreign and native, male and female, and above all the sacred and the profane. It tells the story of different groups of people dealing with one, ostensibly universal, religious activity: the translation and dissemination by French Catholic missionaries of the Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP) of Catholicism in late imperial China, and of the understanding, absorption, and transformation of the message by other actors, specifically rural Chinese Catholics, in their interactions with foreign missionaries—in the particular context of northeast China between the 1840s and the 1900s.

Examining the letters and the historical context in which the missions were produced, this book explores answers to some perennial questions about the ways in which Christianity (Catholicism in this specific case) took root in modern China, and how Chinese Catholics, especially rural and female Catholics, participated in this process to form and transform identity in the context of the nineteenth century.

This is a study rooted in analytical categories: gender and religion, knowledge and behavior, experience and explanation, concept and language, public and private, and imperial and colonial. Understanding how Catholicism took root in local Chinese society requires a study of the mechanisms, institutions, actors, and processes that interpreted the Catholic message through specific language, behavior, and beliefs. This involves pursuing questions such as how the Catholic Church translated the catechism to introduce concepts and rituals of the Christian faith to the Chinese; how it designed regulations that governed missions to enforce church discipline on missionaries, catechumens, and converts; how it made use of systematic parish reports to measure and assess the success of local religious experience; and how local converts, in turn, appropriated this religious language to both articulate and manipulate their new sense of self.

Finally, this is an examination of language, literacy, and a communicative world constructed by two written and oral languages: French and Chinese.1 Language provides historical actors with an important instrument for articulating ideas and emotions. Literacy is the key to success in preserving and transmitting these ideas and emotions reliably. Understanding language through literacy proves particularly important for world religions in a transnational context, for literacy is a prerequisite for any interaction between oral languages and written texts. The intercultural exchange and transformation of ideas depend to a large extent on translation, not only between French and Chinese in this case, but also between the divine and the secular, the numerical and the literal, and the quantitative and the qualitative. This book is an endeavor to unpack the history of this process. It is inspired by Chinese Catholic converts’ appropriation of religious language, their practice of literacy, and their private sentiments, and it ends with an exploration of the models and norms that Christianity and the Catholic missions in China offered to them.

CHRISTIANITY IN MANCHURIA

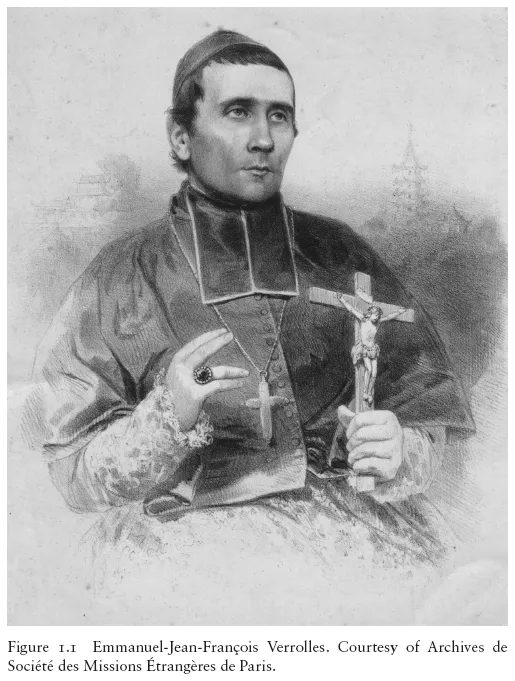

On February 22, 1846, Bishop Emmanuel-Jean-François Verrolles (1805–1878), the first apostolic vicar of Manchuria, delivered a public speech in the cathedral of Metz. After fifteen years in China, including five in Manchuria subsequent to the founding of the mission in 1840, this was Verrolles’s first return to France.

I remained alone. This is why I come back to look for new colleagues. After fifteen years’ absence I see once more the beautiful land of France, the country so dear to my heart, which I will nevertheless leave again, and forever. You may find my language incorrect, maybe even barbaric, but that should not surprise you: when one has lived fifteen years surrounded by Chinese without speaking any language but theirs, it is rather natural that one loses the habit of expressing oneself easily in French. . . . My Chinese Christians are poor, poor to the worst degree. . . . In these missions so desolate whose miseries I have described to you, among people exposed to so many temptations and of such natural timidity, we are nonetheless often comforted and edified by flashes of a heroic faith and courage, worthy of the best ages of the Church.2

Verrolles’s speech deeply moved his audience. In the nineteenth century, as the Catholic revival in Europe and the French government’s imperial goals in the Far East began to converge, French Catholic missionaries formed the vanguard in (re)evangelizing and (re)exploring the vast land of China.3 As one of these trailblazers, Verrolles was the only missionary in the mission when he arrived in Manchuria in 1840. Manchuria turned out to be alien not only to the French audience but also to the early missionaries. Maxime-Paul Brulley de La Brunière (1816–1846), Verrolles’s first assistant, joined him in 1842. He soon felt similarly out of place. In a letter to a friend, de La Brunière complained, “I am a foreigner. I cannot understand well their language, which is so different from that of Jiangnan.”4

A controversial and historically loaded term, “Manchuria” refers geographically to northeast Asia, including the entire region of China’s northeast frontier, which, after the Manchu conquest of China in the seventeenth century, consisted of the three Qing military districts of Shengjing, Jilin, and Heilongjiang.5 This vast area of northeast China, about twice the size of France, was first known as Tartary, according to the writings of early missionaries such as Ferdinand Verbiest (1623–1688).6 By the 1830s, “Manchuria” had emerged as the more common toponym of this region in various accounts and gradually replaced the older term “Tartary.”7 Manchuria was converted into “Three northeast Provinces” by the late Qing government. After the collapse of the Qing in 1911, this region was often known as Dongbei or northeast China. On the map of today’s China, it consists of three provinces: Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang.

As the homeland of the Manchu, who founded the Empire of the Great Qing (1644–1912), the last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, Manchuria remained a significant but relatively isolated frontier area until the early twentieth century. This was largely due to the Qing government’s changing immigration policies, which aimed to maintain the Manchu homeland and to uphold the “Manchu way.”8 In the first two decades after the Manchu took over Beijing, from 1644 to 1667, the Qing government issued a series of edicts to encourage immigration to Manchuria for cultivation. This policy, however, was abolished in 1668. Subsequently, the official Qing ban on immigration to Manchuria by Han Chinese lasted until the end of the nineteenth century. In 1860, the Qing government partially lifted the ban on immigration, and in 1897, the ban was abolished altogether. Because of these policies, the late nineteenth century witnessed a large wave of immigration to Manchuria when various natural disasters afflicted other areas of China.9

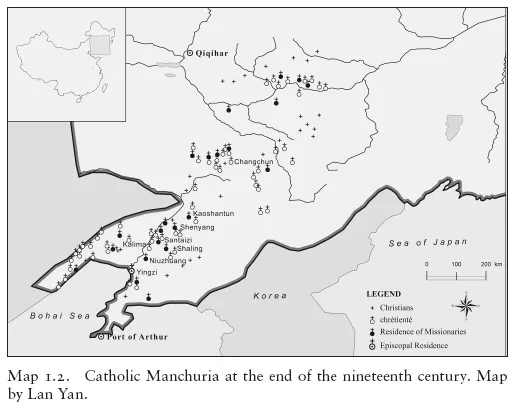

Given this immigration background, one feature of Christianity in Manchuria is that the area’s Christian population predates the presence of missionaries. The earliest Christians in Manchuria may have arrived as early as the fourteenth century from Mongolia.10 When Ferdinand Verbiest visited Manchuria with Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661–1722) in 1682, he recorded that he saw some Chinese Christians who resided in Kaiyuan, a city in Liaodong.11 Later, in the fiftieth year of Emperor Kangxi’s rule (1711), the Portuguese missionary Carlos de Resende (1664–1746) visited Liaodong and recorded that there were more than three thousand Chinese Christians.12 Chinese official documents first recorded Catholics in Manchuria in the twelfth year of Emperor Qianlong’s rule (1747). In their memorial to the throne dated in 1747, Da’erdang’e (?–1758), general of Fengtian, and Su Chang (?–1768), prefectural magistrate of Fengtian, reported that there were eight Catholic churches and more than one hundred Chinese Catholic converts distributed over six counties in the region.13

In the nineteenth century, the majority of Manchuria’s Christians were Catholic migrants from other parts of China. The immigrant Catholic families scattered throughout the vast land of Manchuria, and they included the Du family of Santaizi and the Su family of Biguanbao in Liaoning, as well as the families of Li, Ding, and Xiao of Xiaoheishan in Jilin. The local Chinese gazetteers include many accounts of how immigration brought Christianity into northeast China. In 1796, for example, eight families, including five Catholic families, moved to Bajiazi, which literally means “eight [ba] households [jiazi],” in Jilin. These Catholic settlers did not see a priest until Verrolles visited them in 1842. Verrolles soon decided to build a Catholic community there, and in 1844 a Catholic church was erected in the village.14

Of these Christian immigrants, most were voluntary migrants from Zhili, today’s Hebei, and Shandong, which had been visited by European missionaries since the seventeenth century. There were also involuntary Christian migrants exiled to Manchuria during the century-long prohibition of Christianity started by Emperor Yongzheng (r. 1722–1735) in 1724. During the time of prohibition, the Qing court prescribed that “officials who convert to Christianity be dismissed, [and] common converts be exiled to Xinjiang or Heilongjiang.”15 In his work on Catholic missions in China, the Italian missionary Pasquale D’Elia recorded that in 1814, two Chinese Catholic converts from Guizhou, a southwestern province, were exiled across to the northernmost province of Heilongjiang on the other side of the country.16

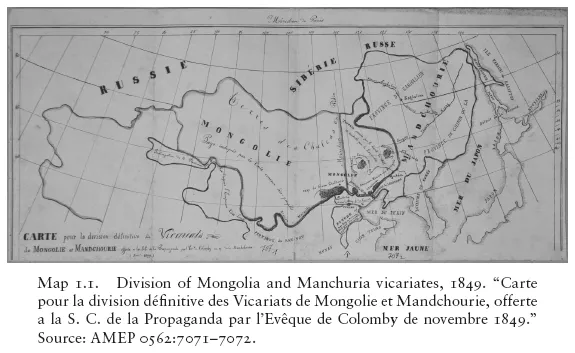

Before Verrolles, only a few missionaries had ever visited northeast China, but the evangelical enthusiasm for the area was longstanding. In the 1650s of the early Qing, Jesuits Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1592–1666) and Johannes Nikolaus Smogulecki (1611–1656) expressed their willingness to go to Manchuria in succession, but both were rejected by Emperor Shunzhi (r. 1643–1661), for the emperor believed Manchuria was too vast and barren to receive missionaries.17 After Pope Alexander VIII established the diocese of Beijing in 1690, Manchuria attracted interest among missionaries in Beijing, some of whom began to make trips to Manchuria to proselytize. These pioneer missionaries included the French missionary Dominique Parrenin (1665–1741) and an unidentified missionary from the Netherlands.18 In 1703, in his letter submitted to the Society of Jesus, Jesuit missionary François Noël (1651–1729) mentioned a Manchu prince, his family, and fifty servants, who all converted to Christianity. He also talked about an ambitious plan to establish a base in Mukden or Shenyang to spread Christianity to Manchuria and further to Korea and Japan.19 Since the seventeenth century, Lazarists and Franciscans had worked in the bordering areas of east Mongolia and west Manchuria. After Verrolles arrived in Manchuria, he noticed that old Christian communities did exist along the border of Manchuria and Mongolia.20 Verrolles located these old Christians in an 1849 map in six established Christian communities, including the Christian community of Xiwanzi in southeast Mongolia, the district of Rehe, and communities in today’s east Mongolia and west Jilin.21

In 1838, Manchuria was detached from the diocese of Beijing, and Pope Gregory XVI established the apostolic vicariate of Manchuria-Mongolia; two years later, the Manchuria-Mongolia vicariate was divided into two. The independent Manchuria Mission, or the apostolic vicariate of Manchuria, was established on August 28, 1840. The Roman Catholic Church entrusted the mission to the French Missions Étrangères de Paris. The MEP’s takeover of Manchuria marked the start of a new age of Catholic missions in northeast China, one conducted under French missionaries and the French protectorate.22

In many ways, the story about Verrolles and his colleagues in the vast land of Manchuria went far beyond these graphical representations. Manchuria is a unique immigrant society. The most recent and largest migration to Manchuria happened in the late nineteenth century along with the rapid expansion of imperialism and Catholic missions in China. For Catholic immigrants newly settled in the vast land of Manchuria, religion became a crucial resource. The missionaries’ agenda to establish a Catholic community and to found a local church also fit the Christian settlers’ desire for stability, security, and a common identity. Thus the development of Christianity in Manchuria was not just about how missionaries converted settlers. It was also about how settlers made use of Christianity to establish their new lives. In many cases, the nineteenth-century Catholic mission did not introduce to local people in Manchuria a new, foreign religion but rather introduced the global institution of the Catholic Church. In this historical process, France and French missionaries, especially the MEP, played a particularly important role.

THE MISSIONS ÉTRANGÈRES DE PARIS AND THE PAYS DE MISSION

It is not accidental that the French Missions Étrangères de Paris emerged as a major player in Catholic Manchuria. A Roman Catholic missionary society devoted to the evangelization of non-Christian countries, the MEP was established in Paris in the late 1650s for the purpose of founding churches, training a native clergy, and supervising Catholic missions.23 This new religious society differed from other comparable Catholic orders in China, such as the Jesuits, the Franciscans, and the Dominicans. The MEP is a société de droit pontifical (society of pontifical jurisdiction) composed of bishops, priests, and brothers. In the nineteenth century, it required all its priests and seminarians to (1) enter the society by the age of thirty-five; (2) meet the prerequisite of at least three years of mission experience; and (3) have either French nationality or French as the mother tongue.24 The French language requirement corresponded closely to the power shift within the Roman Catholic Church, specifically the decline of Portugal and the rise of France.

By the seventeenth century, when the conflict between Rome and the Portuguese Padroado grew severe, the existence of a group of loyal priests became essential to Rome.25 The MEP was directly accountable to the pope and operated under the supervision of the Propaganda Fide, the Roman center of evangelization, which aimed to organize worldwide Catholic missions that would be independent of national rivalries and specific religious orders and congregations. To fulfill the need for priests in mission areas and to free missionaries from the patronage of political powers, the Propaganda Fide established an evangelization order of apostolic vicars above all congregations.26 In the seventeenth century, the stated policy of the MEP was to serve God instead of a specific country or congregation in the Far East. One early MEP priest even wrote in the late seventeenth century, “What could be more stupid than undergoing a dangerous journey to reach this extremely distant land to serve a country or a congregation but not Jesus Christ?”27

Contrary to the missionar...