![]()

1

Setting the Scene

![]()

1

The Bell Tolls

Half the company it used to be

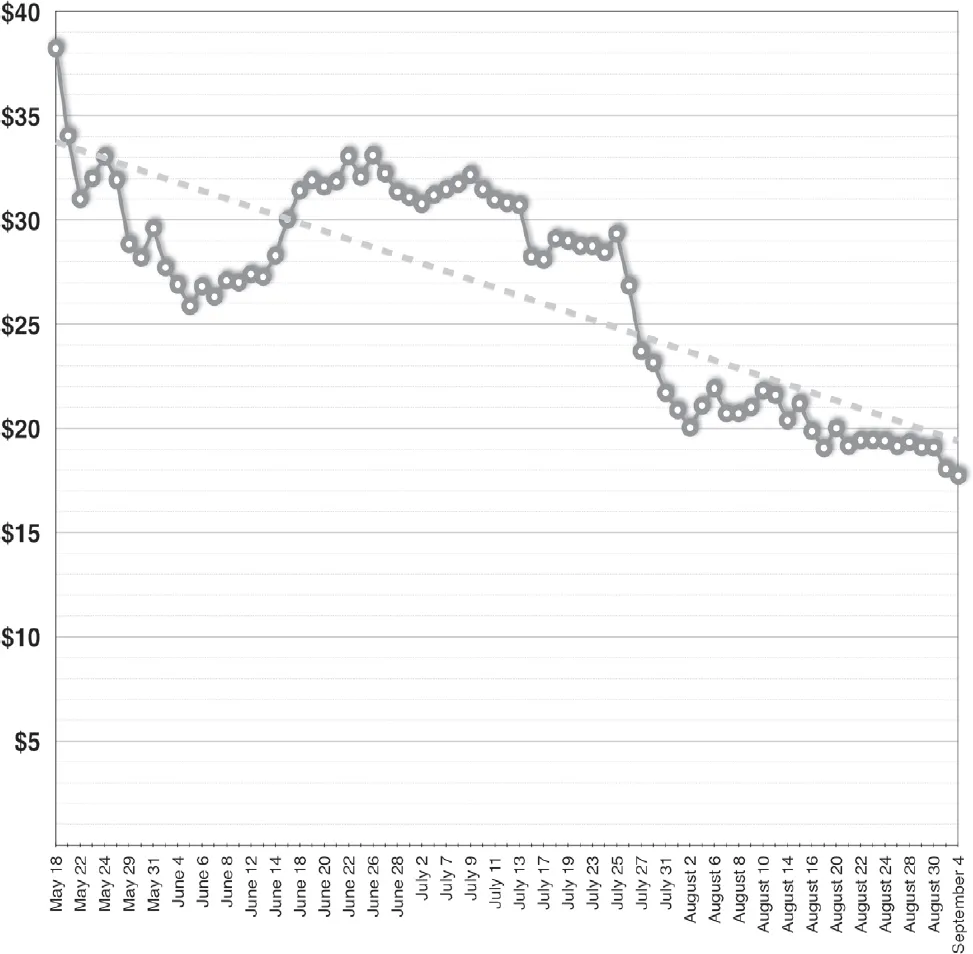

Figure 1-1. Facebook’s closing stock price following its 2012 IPO

(May 18–September 4)

On September 4, 2012, 109 days after standing up in front of an expectant world as the second largest stock market initial public offering (IPO) in US history, Facebook’s stock closed at $17.73, 53%—and more than $50 billion in value—below its hopeful origin as not just a public company but as a referendum on social media. (See Figure 1-1.)

A referendum on Mark Zuckerberg—the wunderkind who had been fictionally immortalized in an Oscar-winning Aaron Sorkin screenplay—for whom “a million wasn’t cool.”

A referendum on Zuckerberg’s vital business partner, Sheryl Sandberg, and her sparkling record in government and business and passion for equality that had not yet expressed itself in a best-selling book but was on display at TED conferences.

A referendum, it seemed, on the very concept of the new Silicon Valley, which was no longer about either Silicon or its valley as networks of shuttles whisked the young software developers who had inherited this part of the earth to and from their preferred San Francisco playground.

There was no saving grace. No apparent way to talk yourself out of the surrounding facts: the overall economy was recovering, and highly regarded technology companies like Google and Apple—hell, even the NASDAQ—were up 10% in the same time frame.

No. Facebook stood starkly alone in its decline, and $17.73 didn’t look like the bottom. BMO Capital was setting their future price estimate at $15, implying Facebook was well on its way to eroding its IPO valuation by a soul-crushing three-quarters. Influential analyst eMarketer announced lower than expected revenue projections for the year. And only a month hence, October 2012 would bring the ending of the post-IPO lockup of 1.2 billion shares of Facebook’s stock, introducing a frighteningly large amount of new supply to overwhelm the already flagging demand for the stock.

Facebook’s new narrative hued more closely to the dismissed carcasses of once high-flying technology darlings like Groupon, Zynga, and MySpace.

“Facebook was not originally created to be a company,” proclaimed its own materials shared with partners to aid them in understanding the company’s unique culture. Maybe, the pundits gathering in droves around the declining company suggested, not-a-company is how it would end.

No Moves Left?

One of the biggest reasons the 53% slide felt much worse than merely a halfway point was that at the time only three consumer technology companies had come back from a decline of that scale to thrive and grow beyond their former glory. They are technology royalty: Apple, Google and Amazon. With hall-of-fame CEOs: Steve Jobs, Larry Page, and Jeff Bezos. As of September 4, 2012, however, the vast majority of observers judging Zuckerberg felt—to paraphrase Lloyd Bentsen’s infamous debate retort—that he was no Steve Jobs. No Larry Page. No Jeff Bezos.

In public, everyone will gladly caution you not to confuse stock price with intrinsic business value. But behind closed doors, these stock downturns usually brought with them vicious cycles of negative external perception and declining internal morale and productivity. They usually made convenient excuses for new and prospective customers to pull back. Usually made recruiting great talent—especially in the obscenely competitive market that is Silicon Valley—much more difficult. And usually disrupted internal flow while management teams scrambled for answers.

Worse yet, leading up to the IPO, Facebook’s leadership—Zuckerberg, Sandberg and others like respected chief financial officer David Ebersmann—had seemingly done everything right. Nine hundred million monthly users. A profitable business. Oversubscribed IPO roadshow. Largest IPO market valuation in the United States.

From the outside, it now appeared, they were out of moves. From the outside, this looked like the end. Or—much worse in the mind of an innovator like Zuckerberg—a long decline to irrelevance similar to the likes of HP and Yahoo. And for 109 days, he had not appeared in public to counter those perceptions.

This is the story of how Facebook got to that point, its amazing recovery and what lies ahead:

Chapter 2 shows how everything at Facebook starts with Mark Zuckerberg.

Chapters 3–

12 are the 10 lessons in Facebook’s rise from also-ran to the recovery from the troubled IPO to becoming the reigning

juggernaut of the most important shift in consumer media in six decades: the unprecedented rise of mobile screens.

Chapters 13–

16 look at the big moves Facebook intends to make in the future and what happens if Facebook wins in all its ambitions.

And

Chapters 17–

18 dissect how failure is a part of Facebook’s success but that even Facebook may eventually get disrupted.

![]()

2

Finding Your Inner Zuck

Everything at Facebook starts with Mark

Zuckerberg, but it doesn’t end there

To tell any Facebook story, you have to first put its lead—Mark Zuckerberg—on stage and give him some context. A path to walk, and a reason to walk it. A tribe to belong to. An origin story from a time before the movie, the hacker’s den in Palo Alto and the Harvard dorm room that hints at how this kid from the comfortable embrace of a close, upper-middle-class American family in the leafy Hudson Valley suburb of Dobbs Ferry 20 miles north of New York City would possibly become a global connector whose work may mean more to people in places like Africa, Southeast Asia, Columbia, Egypt and India than it does even to those in the United States.

Steve Jobs, the patron saint of standout CEOs, during his memorable June 2005 Stanford University commencement address, said, “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.”

Looking backward through Zuckerberg’s life, we see what Jobs meant: the mission to make the world more open and connected has stayed the same for Zuckerberg since the very beginning, he has simply pursued it at an ever larger scope. A scope so large by now that even he—by his own admission—could not have foreseen it in the beginning.

So we go back to that beginning. To the split-level home on that leafy corner of Russell Place and Northfields Avenue in Dobbs Ferry and a pre-teen Zuckerberg—fresh off having been taught programming basics by his dad—building a simple messaging program dubbed ZuckNet to connect the six Zuckerbergs and the computers in their house with those in his dad’s dentist office attached to the house (the Painless Dr. Z they called him in Dobbs Ferry).

Connecting beyond Zuckerberg’s childhood home is a story of motive and opportunity. Motive because that house was separated from Ardsley High School and his friends by a valley with 10 lanes of traffic in the form of the Saw Mill River Parkway and Interstate 87. And opportunity because Zuckerberg, born in 1984, was an early Millennial growing up in an upper-middle-class suburb, making him a member of the first demographic to have computers and the consumer-accessible Internet throughout their teens, allowing them to feel connected all the time, independent of physical barriers and distances, and to build things on top of that connectivity. Zuckerberg has become a global connector not despite his somewhat privileged upbringing but precisely because of it.

To be sure, the Saw Mill River Valley is no DMZ, no border fence, no cultural, economic, political or religious barrier, but it nevertheless drove home for Zuckerberg the power and potential of digital connectedness. And, while he—like all of us—would use search engines to navigate information on the Internet, he realized in those early days that there was no such tool for people. The origins of Zuckerberg as a leader and of Facebook as a company lie in those twin realizations.

But first came CourseMatch, a system that put the social and academic interests of the Harvard community online so students could know more about prospective classmates. Shortly after followed a site with 500 images of Roman art history, shared with the rest of the students in his class to pool notes in order to study for a final exam (on which the students proceeded to get historically high grades). With FaceMash a few months later, he pushed both his development (based on downloading student’s pictures after hacking into data on nine of Harvard’s 12 houses via local networks or the Internet) and the site’s social interactions (asking users to rate the looks of others students) beyond the lines of good taste, copyright law and privacy, landing himself on probation with Harvard and in need of having to apologize to campus women’s groups. Without the misstep of FaceMash, however, which taught Zuckerberg not only to respect privacy but to make controlled data sharing a central feature, it is much less likely that he would have launched thefacebook.com at Harvard the way he did in February 2004.

Having conquered Harvard, U.S. universities followed. Then high school students. Then all Americans. Through translations, Facebook expanded to dozens of—and eventually to more than a hundred—countries (more on all this in Chapter 5). Not satisfied with connecting people in just one way, Facebook developed Messenger and acquired Instagram and WhatsApp (more in Chapters 9 and 13). With their fastest growing app ever, Facebook Lite, they began to support all those around the world who can scarcely afford occasional Internet access, and with efforts including satellites, drones the size of 737s and lasers, they are now looking to connect even the unconnected (more in Chapter 14).

Every journey of connecting billions starts with connecting the first six in your own house. Zuckerberg has simply not stopped since. Looking back, it’s no exaggeration to say that the 32-year-old has been working to make the world more open and connected for more than two decades.

Member of a Very Small Group

During those two decades, he has become a member of a very small group of people who run consumer technology companies that invent the future for us, create the things we cannot live without, and touch hundreds of millions and sometimes billions of lives. Abstract people that, like Beyoncé or Batman, go by a single name: Grove, Jobs, Bezos, Hastings, Page, Zuckerberg, Musk. They become someone we seemingly cannot know, so we settle for the media—and in very special cases, Aaron Sorkin—possibly explaining them to us in oversimplified shorthand: paranoid, mercurial, focused, renegade, cerebral, socially awkward visionary.

They built the microprocessors in our computers and then had the audacity to make us care about what was “inside.” Triggered the advent of the personal computer and ushered in the most sweeping change in consumer technology ever with the iPhone. Built us a store for everything after starting with books out of a garage. Made us “feel lucky” with the quality of search results and launched an operating system now used by 80% of smartphones. Let us watch what we wanted when we wanted and first beat Blockbuster and then traditional television itself. Wrote down a three-step plan to building the first new public American car company to be founded in a century, proceeded to build the best-selling car in its category—which just happened to be electric—and then received nearly 400,000 preorders for a car that didn’t exist. Connected a billion people a day and considered it just a beginning.

They are very unique but have three profound similarities (beside the regrettable fact that they are all white men, an important subject for an entire collection of books that still need to be written beyond Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In):

1. They have the will to keep acting on an “achievable-unachievable” mission: Because they aim for long-term change at large scale, they are doubted, mocked and eventually competed with. Consistently leading progress toward things that do not yet exist in the face of opposition from the outside—and complexity on the inside—may wear down more ordinary leaders, but not this tribe. Steve Jobs’ biggest breakthrough in “building tools for the mind that advance humankind” came thirty years after his first. Jeff Bezos is in his third decade of building “earth’s most customer-centric company.” Kids born the year Larry Page started “organizing the world’s information and making it universally accessible” will be waiting for college acceptance letters this year. Zuckerberg (“make the world more open and connected”) and Elon Musk (“accelerate the advent of sustainable transport”) are just getting warmed up in the second decades of their missions.

The notion of mission had its defining moment in front of the U.S. Congress on May 25, 1961, when the newly elected John F. Kennedy proposed that “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.” Sadly, the vast majority of corporate...