- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

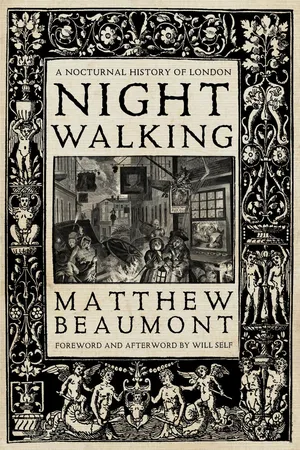

In this brilliant work of literary investigation, Matthew Beaumont shines a light on the shadowy perambulations of poets, novelists and thinkers: the fetid, treacherous streets known to Chaucer and Shakespeare; William Blake and his ecstatic peregrinations; the feverish ramblings of opium addict Thomas De Quincey; and, among the lamp-lit literary throng, the supreme nightwalker Charles Dickens. We discover how the nocturnal city has inspired some and served as a balm or narcotic to others. In each case, the city is revealed as a place divided between work and pleasure, the affluent and the indigent, where the entitled and the desperate rub shoulders.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

1.

Crime and the

Common Nightwalker

The Middle Ages and After

Contrary to Civility

Nightwalking has been a crime for a millennium or more. It has been on the statute books in England and its former colonies since the late thirteenth century. Before then it was a common-law offence. In the medieval period, those who for one reason or another inhabited the streets of London and other cities at night had a proverbial reputation for being villainous, and were liable to be arrested and detained. ‘Night-walkers’ were among those whom Richard of Devizes enumerated as proof of the evils of the capital in his Chronicle of 1192 or 1193: ‘Actors, jesters, smooth-skinned lads, Moors, flatterers, pretty-boys, effeminates, pederasts, singing- and dancing-girls, quacks, belly-dancers, sorceresses, extortioners, night-walkers, magicians, mimes, beggars, buffoons.’ It is a list of those denizens of the city who can under no circumstances be trusted. ‘If you do not want to live with evil-doers,’ he concludes, ‘do not live in London.’1

Vestiges of the long history of legislation against nightwalking in England are visible even today in the United States. In the state of Massachusetts, for instance, you can still technically be arrested as a nightwalker. Chapter 272, Section 53 of the General Laws of the state dictates that, among other malefactors, ‘common night walkers, common street walkers, both male and female’ can be punished by imprisonment for up to six months, or by a fine of up to $200, ‘or by both such fine and imprisonment’.2 A ‘common night walker’ in Massachusetts, as a legal case from the late 1980s indicates, is generally taken to mean ‘someone who is abroad at night and solicits others to engage in illicit sexual acts’.3 On occasion, though, the police invoke the law in order to detain women in poorer neighbourhoods who, instead of soliciting for sex, merely happen to be carrying condoms.

In a contemporary legal context, then, in part because there are more female prostitutes than male ones, the phrase has come to be more closely associated with women than men. It is effectively synonymous with ‘streetwalker’. Historically speaking, however, the term ‘common night walker’ has not been restricted to female prostitutes – as the distinction in the Massachusetts statute book between ‘common night walkers [and] common street walkers, both male and female’ suggests. Indeed, until at least the seventeenth century, so the Oxford English Dictionary indicates, the phrase ‘nightwalker’ was applied fairly indiscriminately to men and women; and thereafter, even if it was increasingly used as a synonym for ‘streetwalker’, it often retained its fuzzy, murky associations with male criminal activities. As recently as the 1960s – the decade in which William Castle’s lurid thriller The Night Walker (1964) appropriated the term and imparted sinister, dreamlike associations to it – there was a case in Massachusetts involving a man convicted of being ‘a common night walker’. He successfully petitioned against this charge precisely on the grounds that the formulation was so capacious as to be unconstitutional.4

Elsewhere in the United States nightwalking continues to be associated with men as well as women, as it was in medieval and early modern England. It indicates all kinds of vagrant activity at night. ‘An idle or dissolute person who roams about at late or unusual hours and is unable to account for his presence’ is the definition of a nightwalker offered by two legal commentators who summarized a number of relevant statutes in the 1960s.5 The ordinance against vagrants in Jacksonville, Florida, for instance, includes a reference to nightwalkers. In its infinite leniency, the state doesn’t construe a single night’s wandering as criminal, necessarily. ‘Only “habitual” wanderers, or “common night walkers”’, the authors of a legal textbook explain, ‘are criminalized.’ ‘We know, however, from experience,’ they rather drily add, ‘that sleepless people often walk at night.’6 The sleepless, the homeless and the hopeless, then, are all susceptible to this archaic charge.

The statute against nightwalkers in Massachusetts, where the Pilgrim Fathers first colonized North America in 1620, was first instituted in the late seventeenth century. In 1660, colonial law made provision that the state’s nightwatchmen should

examine all Night Walkers, after ten of the clock at Night (unless they be known peaceable inhabitants) to enquire whither they are going, and what their business is, and in case they give not Reasonable Satisfaction to the Watchman or constable, then the constable shall forthwith secure them till the morning, and shall carry such person or persons before the next Magistrate or Commissioner, to give satisfaction, for being abroad at that time of night.7

One such magistrate was Thomas Danforth, who investigated the disruptive behaviour of a group of approximately twenty young people, consisting of black people, maids and even students from Harvard University, during the winter of 1676–1677. Thirteen of them were admonished with costs for ‘meeting at unseasonable times, and of night walking, and companying together contrary to civility and good nurture to vitiate one another’, and two others were fined or whipped.8 Nightwalking was indelibly identified with disruptive or subversive social activity. The all-too-familiar fear that black people, women and working-class men might corrupt middle-class youths was a persistent one, and the nightwalker statute in Massachusetts was regularly reinforced by proclamations.

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, as in urban settlements throughout North America, there was in the early modern period no right to the night – particularly for plebeians. The adjective ‘common’, when it appertained to nightwalkers, implied that, in addition to being repeat offenders, the culprits were of mean social station. Almost by definition, the poor could not ‘give satisfaction for being abroad’ after dark. In the streets at night, the itinerant were an inherent threat to society.

Black Spawn of Darkness

The specific origin of the attempt to criminalize the poor at night in late seventeenth-century Massachusetts, later rolled out to other states, lies in England in the late thirteenth century, when a rudimentary national criminal justice system was first instituted. In 1285 Edward I introduced the Statute of Winchester (‘13 Edw. 1’ in the legislative record).

The first of a series of so-called ‘nightwalker statutes’, the Statute of Winchester, or Statute of Winton, was a concerted response to rising crime levels, especially at nighttime, in England’s expanding towns and cities. ‘Because from day to day robberies, homicides and arsons are more often committed than they used to be …’, the relevant section of the statute begins. This legislation ordained that every walled town should close its gates from sunset to sunrise and should operate a night-watch system. The city’s constables or watchmen were expected to arrest strangers abroad at night – by definition suspected of being felons – and to deliver them to the sheriff. Private citizens were also authorized to raise the hue and cry in order to pursue, apprehend and detain those walking about after dark – ‘and for the arrest of such strangers no one shall have legal proceedings taken against him’.9 For the purposes of this statute, implicitly, ‘strangers’ were simply people who failed to carry lanterns or torches – the poor.

Among other measures implemented by the Statute of Winchester in order ‘to abate the power of felons’, then, it confirmed the authority of the night watch. This rudimentary police force – whose principal duty, like that of all police forces, was to protect property – had been introduced in 1253. At that date, as the topographer John Stow indicated in his Survey of London (1598), Henry III ‘commanded watches in the cities and borough towns to be kept, for the better observing of peace and quietness amongst his people’.10 Edward I’s statute instructed these watches, as ‘in Times past’, to ‘watch the Town continually all Night, from the Sun-setting unto the Sun-rising’, and stipulated that, ‘if any Stranger do pass by them’, they should hold them until morning before handing them over to the sheriff.11

Anyone on the streets at night with no good reason was automatically liable to arrest. In the medieval and early modern periods, strangers in the night were feared like evil spirits (the more furtive or predatory of them sometimes blackened their faces so as to conceal themselves or appear more threatening). They were the agents or perpetrators of ‘the works of darkness’ whom St Paul, in his Epistle to the Romans, insists must be cast aside. In the popular imagination, before the diffusion of Enlightenment values in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the identities of vagabonds, robbers, ghosts, demons and other imaginable or unimaginable inhabitants of the night were fluid, if not interchangeable, in the dark.12 Nightwalkers seemed spiritually as well as socially other to respectable citizens (whom priests enjoined, in St Paul’s words again, to put on ‘the armour of light’).

In the labyrinthine spaces of London, prior at least to the institution of street lighting from the end of the seventeenth century, and the concomitant rise of a distinctive ‘nightlife’, the night was intuitively frightening. It retained its ancient biblical and mythological associations with anarchy, chaos and evil – what Shakespeare’s contemporary John Fletcher enumerated as ‘the night, and all the evills the night covers, / The goblins, Hagges, and the blacke spawne of darknesse’.13 In the night, ordinary sounds acquired sinister overtones. The abrupt movement of a shadow glimpsed from the comparative comfort of an interior inspired preternatural or uncanny fear. Even the air at night was thought to be particularly noxious or pestilential. In this climate of heightened tension, prior to its more systematic ‘colonization’ by the culture of the day from the later seventeenth century, any individual who ventured into the streets at night without a light implicitly identified themselves with what Craig Koslofsky has called ‘the Devil’s nocturnal anti-society’.14 The night, in other words, was the domain of felons and demons.

‘The modern city’, Johan Huizinga wrote a century ago in The Autumn of the Middle Ages, ‘hardly knows pure darkness or true silence anymore, nor does it know the effect of a single small light or that of a lonely distant shout.’15 Popular terror of the darkness, which the authorities no doubt exploited in order to preserve social order, made even innocent nocturnal activities – the scramble of a midwife hurrying through the streets to deliver a child, for example – seem intrinsically nefarious, and potentially satanic. Those who loitered in the nocturnal streets without purpose at all, probably because they were homeless, were indefensibly alien. In legal terms, night was ‘an aggravating circumstance’, as the French medievalist Jean Verdon has demonstrated, and criminals therefore received heavier sentences for crimes committed after sunset: ‘Malefactors were not merely infringing the rules of public order; acting under cover of darkness, they were demonstrating their evil intentions, their deep perversity, and premeditation.’16

It is a prejudice that had an ancient, long-established provenance. The Twelve Tables, the legislation that formalized Roman law in the mid fifth century BCE, decreed that, whereas thieves apprehended during the day had to be taken to the magistrates, ‘where anyone commits a theft by night, and having been caught in the act is killed, he is legally killed’. In medieval and early modern London, as in ancient Rome, acts conducted under the cover of darkness were in legal terms stained with the ineliminable pigment of a blackness both moral and mythological.

Prison for Nightwalkers

The Statute of Winchester and its successors formalized the existing common law against male and female nightwalkers. As the great Jacobean jurist Edward Coke formulated it, the provision against nightwalkers was in affirmation of the common law.17 Before 1285, common law had stipulated that citizens were free to detain any suspicious character if he or she proved unable to offer a satisfactory explanation for their presence in the streets after nightfall.

The first book of English common law, the Liber Albus (1419) or ‘White Book’, compiled by John Carpenter, the Town Clerk to the City of London, contained a number of references to cases involving people ‘going or wandering about the streets of the City after curfew [had] rung out’ at the churches in Cheapside (these cases included one chaplain committed ‘for being a nightwalker’). It confirmed that, in order to maintain the peace, it had long been ordained

that no one be so daring as to go wandering about within the said city, or in the suburbs, after the hour of curfew rung out at the church of Our Lady at Bow, unless he be a man known to be of good repute, or his servant, for some good cause, and that with a light; the which curfew shall be rung at the said church between the day and the night. And if anyone shall be found wandering about, contrary to this Ordinance, he is to be forthwith taken and sent unto the prison of Newgate, there to remain until he shall have paid a fine unto the City for such contempt, and have found good surety for his good behaviour.18

To go wandering about in the City of London or its suburbs to the south and west after the night-bell had been sounded was indeed to be daring. ‘Of late walking cometh debate’ is the father’s mild but nonetheless ominous observation in ‘How the Wise Man Taught His Sonne’, a conduct poem composed in Middle English in the early fifteenth century.19

If medieval nightwalkers were not taken to Newgate, they were confined in the Tun, which was purpose-built for their imprisonment. The Tun was a stone construction – so called because it looked like a cask o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction: Midnight Streets

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Part Four

- Afterword

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Nightwalking by Matthew Beaumont in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.