- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

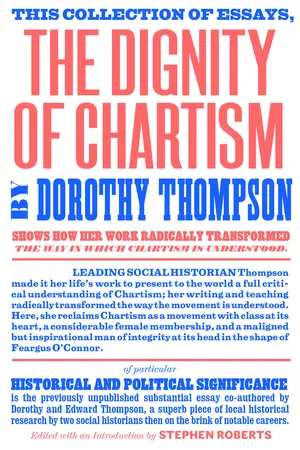

The Dignity of Chartism

About this book

This is the first collection of essays on Chartism by leading social historian Dorothy Thompson, whose work radically transformed the way in which Chartism is understood. Reclaiming Chartism as a fully blown working-class movement, Thompson intertwines her penetrating analyses of class with groundbreaking research uncovering the role played by women in the movement.

Throughout her essays, Thompson strikes a delicate balance between on-the-ground accounts of local uprisings, snappy portraits of high-profile Chartist figures as well as rank-and-file men and women, and more theoretical, polemical interventions.

Of particular historical and political significance is the previously unpublished substantial essay coauthored by Dorothy and Edward Thompson, a superb piece of local historical research by two social historians then on the brink of notable careers.

Throughout her essays, Thompson strikes a delicate balance between on-the-ground accounts of local uprisings, snappy portraits of high-profile Chartist figures as well as rank-and-file men and women, and more theoretical, polemical interventions.

Of particular historical and political significance is the previously unpublished substantial essay coauthored by Dorothy and Edward Thompson, a superb piece of local historical research by two social historians then on the brink of notable careers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

II

A LOCAL STUDY

7

CHARTISM IN THE

INDUSTRIAL AREAS

The history of Chartism has been written more than once from national sources.1 There were a sufficient number of documents in the British Library and the Home Office Papers for the first historians of Chartism to be able to draw a fairly full picture of the movement as it appeared to the authorities in London.2 It should be mentioned that a series of local studies, mainly of industrial centres, is in preparation under the editorship of Professor Asa Briggs of Leeds University. Nevertheless more work remains to be done on the local history of Chartism. One example of the sort of problem on which more light is needed is the well-known division in the movement between the exponents of ‘moral force’ and ‘physical force’. That such a division existed amongst the leadership is very clear from the proceedings of the National Convention of 1839 and from the writings of the movement’s chief journalists (who have often mistakenly been assumed to have been the most influential leaders). However, a study of some local groups in the West Riding, for example, suggests that, although different views on the subject were held, these did not prevent their holders from working amicably together, however much their leaders may have been quarrelling.

What is one to look for in trying to piece together the story in a particular locality? It is clear that the three main periods of activity around the National Petitions of 1839, 1842 and 1848 differed in various ways. These differences become accentuated when a small area is studied, and one of the first points of interest to be established is the level of activity in the area under consideration at these different times. It is also important to note that, although these were the high peaks of national activity, there may have been local outbursts at different times. The second kind of information relates to the form of the Chartists’ activities. These varied considerably from place to place as well as from time to time, and ranged from monster meetings and demonstrations to regular Sunday services with Chartist hymns and sermons, and from torchlight drilling to education classes and choirs. The extent to which Chartists took part in non-political demonstrations such as strikes or agitation for the relief of unemployment varied very much. Local industrial conditions were the determining factor here. In some areas they published their own newspapers and pamphlets and in most areas placards and leaflets. Nearly every important industrial area in the country had some record of Chartist electoral activity, either at the hustings or actually at the poll. An important form of activity about which little is known in most districts is the participation by Chartists in local elections after 1848.3

Having discovered the periods of the greatest activity, and the sort of activity which the local Chartists arranged, the next thing is to gather information about the personalities involved. Who were the local leaders? What were their jobs? How far were they representative of the chief industries of the town? Who were the people who really led the movement? Were they the major national figures who occasionally made visits? Were they local men whose names were little known outside their own towns? Or were the most influential men those intermediate people who did not own newspapers or have already established names outside Chartism, but who became very well-known as travelling missionaries and organizers, e.g. John West and George White?4 What part did women play in the local organization? The answers to these questions will inevitably vary from place to place.

As well as finding out about the Chartists themselves, it is worth asking: who were their allies? Here, perhaps, will be found some of the biggest differences between localities. In the woollen areas, whilst some Tories were sympathetic, the Whigs were hostile. In the cotton towns, however, some sections of the Liberal manufacturers saw the Chartists as possible allies in their fight against the Corn Laws. Such alignments of sympathy varied very much from place to place, but there was certainly not a uniform attitude to Chartism on the part of the established parties. Indeed in the 1847 election, when O’Connor was returned in coalition with the Tory candidate at Nottingham, Ernest Jones secured a sizeable vote in coalition with the radical Edward Miall, editor of the Nonconformist.5 As well as political allies, there were usually tradesman who found it profitable to sympathize with Chartism – most centres had at least one Chartist pub, and often a Chartist grocer and butcher as well.6 Such tradesmen found their sympathies well rewarded when the non-electors practised ‘exclusive dealing’, which was common at election times.

The final point of interest to look out for in the local movement is the connection between Chartism and other movements. This can be particularly well shown in a local study where it is often possible to see the connections in terms of individuals. The ten hours movement, the anti-Poor Law movement and the early trade unions were sometimes sources from which local leaders drew their experiences.7 During and after the Chartist period they worked to found co-operative societies, working men’s clubs, educational and temperance societies, and branches of the Reform League. Nor should the connection with Nonconformist groups be overlooked. A number of local Chartist leaders were recruited from the ranks of Methodist lay preachers.8

The starting point for research into Chartism is the Northern Star. A complete file of this newspaper is preserved in the British Library, but few actual copies have survived elsewhere. The great majority of readers of the Star, as for all other Chartist journals, were working-class, and the houses in which they lived, and in which they might possibly have left newspapers, have long since been destroyed. In any case there is much less likelihood of newspapers being kept in small houses than large, and certainly very little chance of their being bound. The great mass therefore of newspapers, pamphlets, minute books and other records belonging to the Chartists have long since been destroyed. The Star has the very great merit, for our purposes, of always printing full reports of local activity when these were sent in. It had its own reporters in certain large towns, and many of the main national speakers and missionaries were in the habit of sending reports of their speeches and meetings.9 But, in the main, the amount of space devoted to any particular locality depended on the energy of the local secretary in sending in reports of its meetings. Thus, for example, more is heard of the Barnsley group than of many others because Frank Mirfield sent in regular reports of their meetings and of resolutions passed.10

In the Home Office papers most of the reports on Chartism are filed according to counties – although here again there is no consistency in the manner of reporting. It seems that the fullness or otherwise of the descriptions of the events depended very much on the initiative of local magistrates and of other local citizens who felt it necessary to inform the Home Office of what was happening. Amongst the accounts are included a number of pamphlets, placards etc. sent from different places and some of these are of very great interest and value. Odd copies of this sort of material also survives in libraries. It is unfortunate that only a relatively limited number of these are still in existence, as often they seem to have been published when a local group was in disagreement with national policy or when they were at loggerheads with the local press.

Local newspapers vary so much from place to place that it is impossible to generalize as to their value. Some appear to have been published all through the Chartist period without a single reference to it. Others devote many columns to it at peak periods. Some are so fiercely hostile and derisory that their reports, though of great interest, cannot be relied on as to their accuracy. The political sympathies of the newspaper are, of course, of the greatest importance and must be taken into account in assessing its reports, but here again the mid-century alignments are often confusing. A paper which stood for franchise reform and free trade might be very hostile to Chartism whilst a Tory paper like the Halifax Guardian, which had been well-disposed to the ten hours movement, could be more sympathetic, although, of course, fundamentally hostile to the aims of Chartism. Later in the nineteenth century, when Liberalism and free trade were triumphant, it became a popular custom for local newspapers to publish reminiscences of the bad old days. Many of the most interesting recollections of the Chartist period can be found amongst such reminiscences.11

During the periods of greatest activity representatives of most of the centres of Chartism found themselves in the dock – at the magistrates’ court, at quarter sessions or at the assizes. The records of these courts, and the published accounts of trials, should be scanned. Where reported, the magistrates’ comments are of interest, for they are sometimes surprisingly sympathetic and often contain some remark about the superior character of the Chartist prisoners.

_______________

1.This essay was first published in Amateur Historian, III, (1956), pp. 13–19. This is a shortened version.

2.For example, J. West, A History of the Chartist Movement (London, 1920).

3.In 1852 Julian Harney and Samuel Carter appeared on the hustings as Chartist candidates in, respectively, Bradford and Tavistock. Harney, to his dismay, failed to win the show of hands; Carter was elected but, lacking the required property qualification, was soon unseated. Two interesting examples of Chartists who became elected councillors are John Collins of Birmingham and George Holloway (1818–1904) of Kidderminster. Collins was returned as a councillor for Ladywood in 1847; but his attempts to restrain council expenditure proved short-lived when the following year he was incapacitated by a stroke. By turns a carpet weaver, a dyer, a publican and a grocer, Holloway served as secretary and treasurer of the Kidderminster Chartists. Known as ‘Honest George’, he was, with only a few short breaks, a Liberal councillor from 1853 until his death. A number of Chartist councillors were also elected to town councils in the West Riding. For Holloway, see L. Smith, Carpet Weavers and Carpet Masters (Kidderminster, 1986), pp. 248–51.

4.West (1811–87) and White (1812–68) were Irishmen, arriving in England in the 1820s. In 1842–44 West was employed by the NCA as a lecturer in Yorkshire and in 1848 he was imprisoned (with White). A real thorn in the side of the authorities, White frequently found himself in a prison cell: his story is told in Roberts, Radical Politicians and Poets in Early Victorian Britain, pp. 11–38.

5.See Roberts, ‘Feargus O’Connor in the House of Commons’, in Ashton, Fyson and Roberts, The Chartist Legacy, pp. 104–7; C. Binder, ‘The Nottingham electorate and the election of the Chartist, Feargus O’Connor, in 1847’, in Transactions of the Thoroton Society 107 (2003), 145–62.

6.For example, the publican of the Six Bells in Braintree, Essex, provided copies of the Star and local Chartists regularly met there. The Freeman’s Inn in Barnsley, run by Peter Hoey (1807–75), also served as a meeting place for Chartists; Hoey lost the use of a leg during his imprisonment in 1840–41. For Hoey, see C. Godfrey, Chartist Lives, pp. 509–11.

7.For example, R. J. Richardson of Salford was secretary of the South Lancashire Anti-Poor Law Association; William Aitken (1814–69) of Ashton-under-Lyne testified before the Royal Commission on Child Labour in 1833; and Christopher Doyle (1811–?) of Manchester was imprisoned, in 1837, for leading a strike of power-loom weavers. All three men spent time in prison in 1840. For Aitken, see R. G. Hall and S. Roberts, eds, William Aitken: The Writings of a Nineteenth-Century Working Man (Tameside, 1996).

8.For example, John Goslin (dates unknown) of Ipswich, W. V. Jackson (1803–?) of Manchester and Ben Rushton (1785–1853) of Halifax were former Methodist preachers. Jackson was one of the most popular Chartist preachers in Lancashire.

9.Harney, White and Thomas Martin Wheeler (1811–62) were paid correspondents for the Star in, respectively, Sheffield, Birmingham and London in the early 1840s.

10.Frank Mirfield (1801–69) embraced Chartism on returning to Barnsley after being transported, and later pardoned, for leading a weavers’ strike in 1829. He was again to lead a weavers’ strike in 1843–44 and regularly chaired Chartist meetings. See C. Godfrey, Chartist Lives, pp. 520–1.

11.See, for example, Arthur O’Neill in the Birmingham Daily Post in 1885 and W. H. Chadwick in the Bury Times in 1894.

8

‘THE DIGNITY OF CHARTISM’:

HALIFAX AS A CHARTIST CENTRE

(WITH E. P. THOMPSON)

‘Our borough of Halifax is now brightening into the polish of a large, smoke-canopied commercial town’, Miss Lister, owner of Shibdon Hall, noted ironically in her diary in March 1837.1 Head of an old and influential family, owning land, mines and property in the town and environs, her resentment against the March of Progress reminds us that Halifax was no mushroom-growth of the early nineteenth century. The upper Calder Valley, once the classic site of the domestic industry recorded by Daniel Defoe, was a stronghold of the small clothier well into the century. In Halifax there had been built the last of the West Riding ‘Piece Halls’, at which the stuff manufacturers still...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Editorial Note

- Introduction: Rethinking the Chartist Movement: Dorothy Thompson (1923–2011) by Stephen Roberts

- I. Interpreting Chartism

- II. A Local Study

- III. The Leaders of the People

- IV. Repercussions

- V. Looking Back

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Dignity of Chartism by Dorothy Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.