eBook - ePub

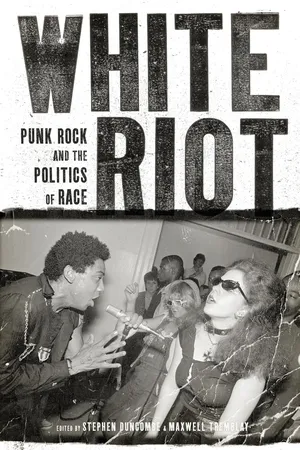

White Riot

Punk Rock and the Politics of Race

This is a test

- 371 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

White Riot

Punk Rock and the Politics of Race

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From the Clash to Los Crudos, skinheads to afro-punks, the punk rock movement has been obsessed by race. And yet the connections have never been traced in a comprehensive way.

White Riot is the definitive study of the subject, collecting first-person writing, lyrics, letters to zines, and analyses of punk history from across the globe. This book brings together writing from leading critics such as Greil Marcus and Dick Hebdige, personal reflections from punk pioneers such as Jimmy Pursey, Darryl Jenifer and Mimi Nguyen, and reports on punk scenes from Toronto to Jakarta.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access White Riot by Stephen Duncombe, Maxwell Tremblay, Stephen Duncombe,Maxwell Tremblay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Punk Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Punk MusicTHREE

WHITE MINORITY

We’re gonna be a white minority

We won’t listen to the majority

We’re gonna feel inferiority

We’re gonna be a white minority

White pride

You’re an American

I’m gonna hide

Anywhere I can

—“White Minority,” Black Flag

How to make sense of Black Flag’s “White Minority”? Is the 1980 hardcore song a racist call to arms that Whites are becoming a minority in Southern California, or is Black Flag parodying White fears? Is articulating whiteness though punk rock a racist gesture, or an honest acknowledgment of a racial identity in an increasingly ethnically heterogeneous society? Who is the “we,” the “you,” and the “I” of the song, and who is the audience supposed to identify with? Finally, are the answers to all these questions complicated by the fact that the lead singer and drummer for Black Flag at the time were both Latinos and the producer of the song was black? It’s hard to make sense of the racial politics of “White Minority” through the simple prism of White/Other or racist/antiracist … and that’s exactly what makes the song, and the context that produced it, so interesting.

In the mid 1970s to early 1980s, concurrent with the rise of punk rock, White supremacy in the United States and Britain was being contested politically, culturally, and demographically. Whites in these countries could no longer live the fantasy of universality, wherein White is the given and everything else is Other, particularly not in cities like Los Angeles, New York, and London. No longer assumed as universal, whiteness began to be articulated as a conscious subject position. But this position was unsettled and volatile, finding versions of itself expressed in both the rising tide of liberal political correctness as well as the conservative revolutions of Thatcher and Reagan. Distancing themselves from both these options, punks staked out a terrain of whiteness that attempted to defy simple categorizations like liberal or conservative, tolerant or bigoted.

In punk, whiteness became something to be discussed and demonstrated; its definition, however, remained elusive. This undecided and oppositional quality of punk whiteness led cultural and political critics, from both ends of the spectrum, to define punk’s racial politics in ways that made sense to them, but punk itself eluded such easy categorization. For the first wave of New York and London punks, symbols of starkly racist whiteness were mobilized for shock value; for the hardcore band Black Flag, whiteness was something to be ridiculed; for Minor Threat and the Fuck-Ups, whites were under attack; for bands like X, the White race had become merely one among many; and for Sham 69, race took a backseat to categories like youth and class. Punk whiteness at that moment and under these circumstances was inchoate and ambiguous: it was self-conscious, dejected, oppositional, and anxiety-ridden, with its political content still up for grabs. Yet it’s important to remember that race, even hazily defined, has salience: redefining whiteness didn’t release punks from the White race’s place and privilege.

Nevertheless it’s an opening. Forced to acknowledge their own racial history and specificity, it’s a moment of opportunity for White punks to forge an oppositional whiteness against dominant definitions. In this context, Black Flag’s lyrics, “We’re gonna be a white minority / We won’t listen to the majority,” take on new meaning.

STEVEN LEE BEEBER, “HOTSY-TOTSY NAZI SCHATZES: NAZI IMAGERY AND

THE FINAL SOLUTION TO THE FINAL SOLUTION”

In this selection Steven Beeber makes the provocative claim that punk, in its early New York iteration, was an extension of characteristically Jewish cultural tropes, and further, that without the historical experience of the Holocaust, punk rock as we know it simply would not be. The locus of both of these arguments lies, for Beeber, in the New York punks’ appropriation of Nazi imagery and, in particular, the swastika. Situated in the context of protopunk provocateurs like Lenny Bruce, New York punk comes out as a struggle over the meaning of Jewishness. This, interestingly, takes the question of “race” out of the traditional White/Other binary, constituting “a rebellion against the Jewish desire to be taken seriously by the predominant culture.” The singularity of this as a cultural moment cannot be overstated, since, as we will see, the use of the swastika in the British context turns out to be something interestingly different from “Jewish revenge.” However, this introduces a valuable new thread: a subtle turn from a sincere White appropriation of non-White cultures into an aesthetics of shock, in which appropriations of extreme whiteness are refigured as ironic signs of a countercultural ethnic identity that isn’t quite White.

Author’s Note: According to rumor, the following scene is true. While I can make no definitive statement as to its veracity, I heard it from at least two highly placed sources who prefer to remain nameless. Understandably.

In a bedroom somewhere in the East Village, Chris Stein and Debbie Harry are making love, a Nazi flag beneath them, its red backdrop in perfect counterpoint to her blonde hair.

Meanwhile, in another apartment nearby, Dead Boys lead singer Stiv Bators and his Jewish girlfriend Cynthia Ross are doing the same, her equally blonde hair splayed out against the black swastika in the middle, its bent arms radiating around her face in sieg heil–like salutes.

And not far from there, Stiv’s bandmate Cheetah Chrome is similarly engaged on his Nazi-flag bedspread with his half-Jewish girlfriend Gyda Gash, her dyed-blonde hair free from its vintage Feldkommandant’s cap that goes so well with her matching tattoos of a Jewish star and the word STIGMATA.

Is it surprising to find so many punk principals involved in the same pursuit? Everyone knows that the punks were attracted to the dark side, and that they liked to shock their audiences both onstage and off. But what to make of the fact that in each of these instances, one of the participants is Jewish—at least in part? Both Chris Stein and Cynthia Ross had Jewish parents, and Gyda “Braverman” Gash had a Jewish father and Catholic mother.

Moreover, what to make of that other punk couple, Sid ’n’ Nancy, he of the swastika T-shirts and she of the Jewish family in the Philly suburbs? Or of the five Jewish guys in the Dictators who played “Master Race Rock”? And don’t forget early punk champion and child of Holocaust survivors Genya Ravan, or Dictators’ press secretary and fellow child of a Holocaust survivor, Camilla Saly. Or Lou Reed and the iron crosses shaved into his hair, Jonathan Richman and his song about trains going through the Jewish suburbs of Scarsdale and New Rochelle, and Daniel Rey (Rabinowitz) and his band Shrapnel. Is there something sinister at work here? Something horrific? Something camp, perhaps? Say, concentration camp?

As we’ll see, it’s a mixture of all of these things. While the various punk responses to the Holocaust range from the mocking to the shocking to the world-rocking, as in the impulse to identify with the oppressors, each is in its own way an attempt to deal with this tragedy that affected the punks’ lives whether they like to admit it or not. No Holocaust, no punk. As many a Jewish parent had pointed out to his or her dismissive child, it didn’t matter whether you were religiously Jewish, culturally so, or completely apathetic about the link—it didn’t even matter whether you were Jewish at all: if you had one Jewish grandparent, that was enough to get you gassed in Nazi Germany. Christ, even one great-grandparent could do it sometimes. You could scream and cry all you wanted, but it made no difference. The field of red and the white circle surrounding the black swastika in the middle would get you. It would put the agony to your ecstasy. Its purifying fire would burn you to your very core.

Even if you weren’t worried about what might have happened to you in Nazi Germany, the Holocaust had an impact on you as a Jewish punk. As Andy Shernoff observed, it made you embarrassed that you were descended from a people who had allowed themselves to be so victimized. That’s why he and others were so proud when Israel beat the combined forces of four Arab nations in the Six-Day War, and why folks like Chris Stein collected Nazi memorabilia even after they made it as stars. It was not to glorify their oppressors but to show that, as Debbie Harry explained, “he had won, the Jews had won.”

Of course, the thrill of breaking taboos did play a part. When Chris Stein and his best friend, Glenn O’Brien—editor of Interview magazine and for a number of years in the late 1970s co-creator and host with Chris of the local cable access show TV Party—were on their way home from the airport, where Chris had just picked up a specially delivered ceremonial sword of Himmler’s, Chris suggested that they should stop at a synagogue to “see how everyone would react.” O’Brien says, “He seemed to think that it would be funny to stop at a synagogue. He had a weird gleam in his eye.” …

The combined elements of horror and satire that undermined the social order were as Jewish as they were New York as they were punk. …

In both MAD magazine and the comedy of Lenny Bruce—not to mention to a lesser degree in the spiels of contemporary Jewish “humorists” such as Mort Sahl and Shelly Berman—this loud, irritated funniness that satirized social proprieties and institutions was fed by a larger distrust of governments, legal systems, and even history. Bruce attacked everything from the Catholic Church to the liberal Democrats of the Kennedy administration to the “authorized” purveyors of the story of the Holocaust in an effort to make his audience look below the surface, because he felt that civilization was drowning in hypocrisy. Whether he was simply attempting to make light of the Shoa so as to ease its horror, or attacking those who had begun to use it to promote a political agenda (chiefly in Israel), Bruce employed humor to undermine the accepted norms, a Jewish response throughout millennia of living on the fringes of society that was exaggerated all the more in the period following the Holocaust.

As distance in time provided the psychological and political safety to address the Holocaust more directly, it, like any other historical event, was interpreted variously, sometimes for competing purposes. Intellectuals such as Hannah Arendt saw in it an example of the “banality of evil”—the ability of shallow bureaucratic humans to commit murder dispassionately whether they were Jewish or not. Zionists saw in it a rationale for the establishment and defense of Israel, a Jewish state that would put the safety and interests of Jews first. Bruce saw the Holocaust as merely another in a long line of crimes against humanity perpetrated by humans of every stripe. In one of his most controversial bits he makes an analogy between (1) the Holocaust, (2) the Allies’ fire-bombing of Dresden, and (3) America’s use of atomic bombs in Japan. As he says, affecting an exaggerated accent in the spirit of Dr. Strangelove: “My name is Adolf Eichmann. And the Jews came every day to what they thought would be fun in the showers. People say I should have been hung. Nein. Do you recognize the whore in the middle of you—that you would have done the same if you were there yourselves? … Do you people think yourselves better because you burned your enemies at long distance with missiles without ever seeing what you had done to them? Hiroshima auf wiedersehen.”

Clearly not everyone’s cup of methadone, but for a generation that was increasingly hearing—in after-school Hebrew classes, synagogue sermons, and movies such as The Pawnbroker (1965)—about the evils done to its people at the hands of others, it was a message that was felt, absorbed, and to a certain degree openly acknowledged. For if one is raised to see the Nazis as the enemy and the Jews as the good guys (not to mention the victims), when it comes time to rebel, who are you going to side with? Especially when it is the nature of your people to examine the position of the outsider, the maligned other rejected by the status quo, the enemy of the state? If you’re a Jew, and the Jewish and non-Jewish powers-that-be tell you the Nazis are bad, then aren’t you going to want to mess with that dynamic a bit? Like Lenny Bruce, aren’t you going to want to throw it in their faces for shock value at the very least? Aren’t you going to want to upset them as much as you can—just as a generation made up of your older siblings had done by adopting the rhetoric and slogans of the communists so despised by all (including Jewish parents who were often embarrassed by their own parents’ socialist pasts)? Furthermore, aren’t you going to want something even stronger, considering that most of those former radicals were already becoming fine, upstanding New Age Yuppies? Where had all the Yippies gone with their self-righteousness, their revolution, their hopes for a brighter future? There was no future. And you, their younger siblings, were tired of hearing about the fascist state of Amerika. You were ready to attack everything, while perhaps buying bulletproof vests for the cops. You were ready to adopt the look and attitudes of the fascists, no matter how complicated, simpleminded, or ill-guided your motivations might have been.

This trend emerged in the late 1960s, in England, the only place where a swastika might be as disturbing to non-Jewish parents as to Jewish ones. Here, with the Rolling Stones, the first widely circulated images of rock stars in Nazi uniform appear. Brian Jones and his German girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg, did it first, followed by Keith Richards, now the paramour of the lovely Anita, Keith Moon of the Who, and Ozzy Osbourne of Black Sabbath, to name just a few. All these bad boys of the British Invasion shared a historical background that had been turned upside down by the war. As any historian—or moviegoer (see John Boorman’s Hope and Glory, 1987)—knows, before the Second World War the sun never set on the British Empire, vast swaths of the globe colored in that most royal of colors, pink. When the Germans finished off the job they had begun in the First World War, however, draining the British of their capital reserves and the will to fight uprisings across their domain, the empire all but crumbled overnight. Suddenly, England was reduced to a single, ration-hungry, bombed-out, gray island that throughout the 1950s was ruled by gangster youths and hooligans, many of whom, being Jewish, were not even “real” Brits (more on this to come). In reply to an upper-crust gent’s indignant comment, “I fought the war for your sort,” one of the original Brit invaders, Ringo Starr, said, “I bet you wish you hadn’t won.”

It isn’t such a leap from here to Johnny Rotten’s screaming “Belsen Was a Gas,” while his loutish bassist Sid Vicious carved swastikas into his chest. With two hundred years of world domination destroyed by the Nazis it’s not surprising that the wild—and perhaps disappointed—children of those who “won the war but lost the peace” might rebel in the very way that would hurt their parents most—by identifying with the enemy and in many cases adopting the same enemy’s philosophy. …

Before we get into New York punk’s connection to Nazi themes, let’s look back just once more—this time at pre-punk America. The Rolling Stones, among the first to adopt Nazi regalia on a large scale, were here imitated by less well known yet ultimately equally influential bands such as the Stooges, adored by punk impresario Danny Fields, and later, the Blue Öyster Cult, so important to the burgeoning New York rock scene.

In the case of the Stooges, the impulses are closer to those that emerged in England—economic dissatisfaction at the closing of auto plants around their native Detroit. Like the Dead Boys of Ohio, another punk Rust Belt band, th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword James Spooner, director of Afro-Punk

- One White Riot?

- Two Rock ’n’ Roll Nigger

- Three White Minority

- Four White Power

- Five Punky Reggae Party

- Six We’re That Spic Band

- Seven Race Riot

- Eight I’m so Bored With the USA (And the UK too)

- Notes

- Permissions