![]()

1

Politics as a Descriptive Science

I do not care if men be vicious so long as they are intelligent. […] Laws will do everything.1

Claude-Adrien Helvétius

[…] le tribunal suprême & qui juge en dernier ressort & sans apel de tout ce qui nous est proposé, est la Raison […]2

Pierre Bayle

The people […] are cattle, and what they need is a yoke and a goad and fodder.3

Voltaire

I

THE CENTRAL ISSUE of political philosophy is the question ‘Why should any man obey any other man or body of men?’ – or (what amounts to the same in the final analysis) ‘Why should any man or body of men ever interfere with other men?’

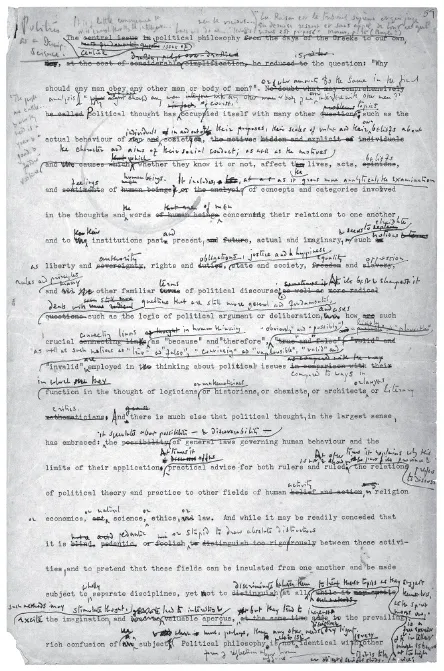

The first page of the main manuscript of PIRA

Political thought has, of course, occupied itself with many other topics: such as the actual behaviour of individuals in and out of society, their purposes, their scales of value and their own beliefs about the character and aims of their social conduct; as well as the motives and causes which, whether they know it or not, affect the lives, acts, beliefs and feelings of human beings. It includes, as it grows more analytical, the examination of the concepts and categories involved in the thoughts and the words of men concerning their relations to one another, and to their institutions past and present, actual and imaginary, and seeks to elucidate such notions as liberty and authority, rights and obligations, justice and happiness, State and society, equality and oppression, rules and principles, and many other familiar terms of political discourse. At its best and sharpest it deals with questions that are still more general and fundamental, such as the logic of political argument or deliberation, and asks how such crucial links in human thinking as ‘because’ and ‘therefore’, ‘obviously’ and ‘possibly’, as well as such notions as ‘true’ and ‘false’, ‘convincing’ and ‘implausible’, ‘valid’ and ‘invalid’, are employed in thinking about political issues, as compared to the ways in which they function in the thought of logicians, or mathematicians, or historians, or chemists, or architects or lawyers or literary critics.

There is much else that political thought, in the largest sense, has embraced. It speculates about the possibility – and discoverability – of general laws governing human behaviour, and the limits of their application. At times it offers practical advice for both rulers and ruled. At other times it explains why this is not, and should not be, part of its province, and prefers to discuss the relations of political theory and practice to other fields of human activity – religion, or economics, or natural science, or ethics, or law. And while it may be readily conceded that it is pedantic or stupid to draw absolute distinctions between these activities, and to pretend that these fields can be insulated from one another and be made subject to wholly separate disciplines, yet not to discriminate between them at all, to treat these topics as they suggest themselves, as the spirit moves one, is a free exercise of the intellect which is bought at too high a price. Such methods may stimulate thought, excite the imagination, and lead to interesting and valuable aperçus, but they tend to increase the prevailing rich confusion of a subject which more, perhaps, than any other needs discipline and dry light if it is to be an object of serious study.

Political philosophy is what it is and not identical with every other form of reflection about human affairs. Its frontiers may have grown indistinct, and it may be arid scholasticism to erect artificial barriers, but it does not follow from this that it has not a province of its own. As things stand at present, it seems to me a greater service to the cause of lucidity and truth to try to indicate what this province is, however provisionally, rather than to pretend either, as some have done, that it is a province of epistemology or semantics – that nothing useful can be said unless and until the ways in which words are used in political argument have been properly compared and contrasted with other ways of using words (valuable and indeed revolutionary as this analysis, in the hands of a man of genius, could be); or, as others tell us, that politics is part of a larger whole (the whole of human history or the material evolution of society or some timeless order), and can and must be studied only within that whole or not at all. And it is because so much has been urged in favour of these ambitious schemes that I propose more modestly to assume, at any rate by way of a tentative initial hypothesis, that at the heart of political philosophy proper is the problem of obedience, and that it is, if nothing else, convenient to view the traditional problems of the subject in terms of this problem.

To put the question in this way is to be reminded of the rich variety of the answers to it. Why should I obey this or that man or group of men, or written or spoken enactment? Because, says one school of thought, it is the word of God vouchsafed in a sacred text of supernatural origin; or communicated by direct revelation to myself; or to a person or persons – king or priest or prophet – whose unique qualifications in such matters I recognise. Because, say others, the command to obey is the order of the de facto ruler or his chosen agents, and the law is what he wills and because he wills it, whatever his motives or reasons. Because, say various metaphysical Greek and Christian and Hegelian thinkers, the world has been created, or exists uncreated, to fulfil a purpose; and it is only in terms of this purpose that everything in it is as it is, and where and when it is, and acts as it does and is acted on as it is; and from this it follows that a particular form of obedience to this rather than that authority, in specific circumstances and in special ways and respects, is required of a being such as I am, situated in my particular place and time: for only by obeying in this way will I be fulfilling my ‘function’ in the harmonious realisation of the overall purpose of the universe.

Similarly other metaphysicians and theologians speak of the universe as the gradual unfolding in time of a ‘timeless’ pattern; or of human experience as a reflection, less or more fragmentary or distorted, of a ‘timeless’ or ‘ultimate’ reality, itself a harmonious system, wholly concealed, according to some, from the gaze of finite beings such as men; partially or progressively revealed, according to others. The political arrangements – and in particular those of obedience – derive from the degree of perception of social facts that the depth of understanding of this reality affords. But again there are those who have said that I must obey as I do because life would be intolerable to me unless a minimum of my basic needs are fulfilled, and a particular form of obedience is either a wholly indispensable, or else the most convenient and reasonable, method of securing this necessary minimum.

There is the celebrated school which affirms, still in answer to the same question, that there exist laws universally binding on all men, whatever their condition, called natural law, in accordance with which I am obliged to obey, and, alternatively, to be obeyed by, certain persons, in certain situations and respects. If I infringe this law (which according to Grotius even God cannot abrogate, since it flows from the ‘rational’, that is, logically necessary, ‘nature of things’ like the laws of mathematics or physics) I frustrate my own deepest wants and those of others; cause chaos; and come to a bad end. It is a corollary of this view that these basic requirements – and the laws which make possible their satisfaction – necessarily spring from the purposes for which I was created by God or nature; hence the natural law is the law which regulates the harmonious functioning, each in its appointed fashion, of the components of the universe conceived as a purposive whole.

Closely related to and historically connected with this view is the doctrine that I possess certain rights, implanted in me by nature, or granted to me by God or by the sovereign, and that these cannot be exercised unless there is an appropriate code of laws enjoining obedience by some persons to others. This doctrine too may form part of a teleology – a view of the world and of society as composed of purposive entities in a ‘natural’ hierarchy – or it may be held independently, where ‘natural rights’ are conditioned by needs which spring from no discernible cosmic purpose, but are found universally as inescapable and ultimate parts of the natural world and the system of cause and effect, as Hobbes and Spinoza thought.

There is the equally famous doctrine that I am obliged to obey my king or my government because I have of my own free will promised, or because others have promised for me, that I shall obey and be obeyed according to certain rules, explicit or implicit; hence not to do so would be equivalent to going back on my undertaking, and that is against the moral law which exists independently of my undertakings. And there are many more answers with a long tradition of thought and action behind them. I obey because I am conditioned to obey as I am doing by social pressure, or by the physical environment, or by education, or by material causes, or by any combination or by all of these. I obey because it is right to do so, as I discern what is right by direct intuition, or moral sense. I obey because I am ordered to do so by the general will. I obey because to do so will lead to my personal happiness; or to the greatest happiness of the greatest number of other persons in my society; or in Europe; or in the world. I obey because in doing so I am fulfilling in my person the ‘demands’ of the world spirit, or the historical destiny of my Church or nation or class. I obey because I am spellbound by the magnetism of my leader. I obey because I ‘owe it’ to my family or my friends. I obey because I have always done so, out of habit, tradition – to which I am attached. I obey because I wish to do so; and stop obeying whenever I please. I obey for reasons which I feel but cannot express.

What all these celebrated historical doctrines, which are here set forth in an oversimplified form – almost in a Benthamite caricature – have in common is that they are answers to the same fundamental question, ‘Why should men obey as, in fact, they do?’ Some are also answers to the further question, ‘Why do men obey as they do?’, and some are not; but the answers to the former are not necessarily answers, or parts of the answers, to the latter question as well – their raison d’être is that they are answers to the first, the ‘normative’, question, ‘Why should a man obey?’ If the question had not presented itself in this way in the first instance, the answers, and the battles about them which are so great a part of the history of human thought and civilisation, would scarcely have taken the form they have. Hence its unique importance.

I have called the question normative, that is, a question requiring an answer of the form ‘ought’ or ‘should’, rather than descriptive, that is, answerable by ‘x is’ or ‘x does this or that’, but this distinction, now so deeply rooted as not to need elaboration, is scarcely noticeable before the middle of the eighteenth century. This fact is of crucial importance. For it rests on an assumption that is universal, tacit, scarcely questioned in all the centuries that preceded Kant, namely that all genuine questions must be questions about matters of fact, questions about what there is, or was, or will be, or could be, and about nothing else. For if they are not about the contents of the world, what can they be about? The perennial issues with which the great thinkers occupied themselves – How was the world created? What is it made of? What are the laws that govern it? Has it a purpose? What, if any, is the purpose of men in it? What is good, what is permanent? What is real and what is apparent? Is there a God? How does one know him? What is the best way of living? How can one tell that one has discovered the correct answers to any questions? What are the ways of knowing what are the criteria of truth and error in thought, or of right and wrong in action? – all such questions were, as often as not, regarded as resembling one another in that they were all enquiries about the nature of things in the world; and, furthermore, as being of the same kind, ultimately, as such quite obviously factual questions as: How far is Paris from London? How long ago did Caesar die? What is the composition of water? Where were you yesterday? What are the most effective means of becoming rich, or happy, or wise?

Some of these questions seemed easier to answer than others. Any well-informed person could tell you the distance between two towns, or indicate how to set about answering the question for yourself, or how to check the answers of others. It required more knowledge and more technical skill to analyse water; perhaps still more to discover how to make yourself or your community prosperous; and only the greatest sages, armed with an immense range of knowledge, and very exceptional moral and intellectual gifts, perhaps special faculties – ‘insight’, ‘depth’, ‘intuition’, ‘speculative genius’ and the like – were thought capable of acquiring even so much as a glimpse of the true answers to the great but dark problems about life and death, about the vocation of man, about the true purposes of human society, about truth and error in thought and the right and wrong goals of action – the great questions which had tormented thoughtful men in every generation. But no matter how unattainable the required range of knowledge, or rare the special faculties without which these crucial truths might remain for ever shrouded in darkness, the task was assumed to be fundamentally similar to that of any other factual enquiry, however humble. The questions themselves were more or less intelligible to anyone with an enquiring turn of mind; the answers might be enormously difficult to discover, but the necessary data existed somewhere – laid in the mind of God, or in the mysterious arcana of physical nature, or of some mysterious region to which only a small number of privileged persons – seers or sages – had access; or perhaps they might, after all, be discoverable by systematic and coordinated labour conducted in accordance with the principles of this or that discipline – say, mathematics or theology or metaphysics – or perhaps of some empirical science.

However wide the disagreements about the attainability of such knowledge, or about the correct methods of investigation, one common assumption underlay the entire discussion; namely that no matter how complex a riddle might be, if it was genuine, and not simply a form of mental or verbal confusion, the answer to it – the one true answer – lay in a region in principle attainable, if not to men, then to angels; if not to angels, then to God (or to whatever omniscient entities atheists, or deists or pantheists, might appeal). The assumption entailed that every genuine question was genuine precisely in the degree to which it was capable of a genuine answer; the answer, to be ‘objectively true’, must consist in facts – or patterns of things or persons or other entities – which are what they are independently of thoughts, doubts, questions about them. At worst, being but finite, fallible, imperfect creatures, we may be doomed to eternal ignorance on the most essential issues; but the answers must be knowable in principle, even though we shall never know them; the solutions exist, as it were, ‘out there’ in the unknown regions, though we may never be allowed to see them: otherwise what is our enquiry about? What limits our knowledge? Of what does it fall short?

The issue on which for centuries, indeed since the Greeks had first raised it, everything turned was how to be sure where true wisdom lay. And wisdom, however gained – whether by learning or revelation or innate genius for obtaining the truth – consisted above all in comprehending the nature of the world – the true facts – and of man’s place – and prospects – in it. The possessor of such knowledge was looked up to with hope and awe and placed high above the heads of conquerors or heroes, for he alone held the keys of the kingdom – could tell men how to live, what to do, and what would be their fate hereafter. Human and divine – Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle; the Stoics and Epicurean sages; Moses, the Buddha and Jesus, Muhammad, their apostles; and more lately Bacon or Descartes, Leibniz or Newton and their disciples – they knew the true facts.

It was like the search for the philosopher’s stone in spiritual as well as material matters. There was no agreement about where the expert was to be found. Some looked for him in the Church, others in the individual conscience; some in metaphysical intuition, others in the simple heart of the ‘natural’ man; some in the calculations of mathematicians, others in the laboratory or in worldly wisdom or the mystic’s vision. Somewhere the sage, the man who knew, was, at any rate in principle, capable of existing; if his views were true, those of his rivals were necessarily false – if only about what mattered most – and thus deserving of extermination by every possible means.

The great controversies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries between Catholics and Protestants, theists and sceptics, deists and atheists, intuitionists and empiricists – and within these camps themselves – for the most part derive from differences of view about where true knowledge was. Political wisdom was, above all, a matter of expertise, skill, the proper method of acquiring and applying the relevant information. The Jesuits taught, for example, that only the Roman Church could provide the true answer to the question whether it was right to obey a given government or sovereign, because it followed from the larger question of why man was created, by whom, and for what purpose, and what his duties were at any given point of his historical career; and that these questions – which were questions of theological fact – could be answered only by those who had expert knowledge of this province of human knowledge – in this case divinely appointed persons who, in virtue of their sacred office, were endowed with special knowledge inherited from their predecessors as well as unique powers of discriminating the truth in these matters.

Against this, various Protestant sects maintained that the proper solutions were not confined to the minds of a set of experts, linked by continuous historical tradition, but could be discovered in the heart of any Christian man attuned properly to hear the voice of God. Bossuet held that national traditions had a special part to play in the attainment of that state of mind in which men of various countries and ways of life had been vouchsafed by God a vision of the true facts of the case – each in the peculiar light with which their traditions irradiated the central single truth – and that the wills and actions of individual monarchs, in virtue of the peculiar functions with which they were endowed by God, were if anything surer indications of the divine will than the pronouncements of theological experts in the service of the Pope.1 Spinoza, on the other hand, supposed that only individual human beings had wills and purposes, whereas the universe as a whole, not being a person, could have none; nor had it been created to serve God’s purpose, for no personal creator, and so no divine tactic, knowable or inscrutable, existed. But men, being endowed with reason, could, if they patiently exercised it, and kept it unobscured by passions, presently perceive the connections which exist between everything that exists in the world; connections called ‘necessary’ because to be aware of them was not merely to be face to face with what there is, but also to grasp why everything was necessarily what it was, and where and as it was, in relation to everything else – not merely seemed to be, but really was. If you wished to know whom you should obey, and when, and under what circumstances and why, this could be discovered, like everything else, only by examining the facts in t...