![]()

BIRDS

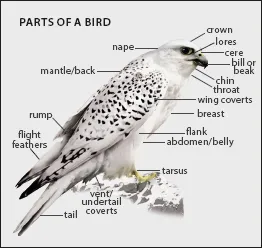

FEATHERS ARE THE DISTINGUISHING FEATURE OF BIRDS. Birds are also characterized by having a bony beak with no teeth, forelimbs modified into wings, a skeleton with hollow bones, and a four-chambered heart. They are warm-blooded (ectothermic) and have a high metabolic rate. They lay eggs (oviparous). Birds walk, hop, and run on two legs, and almost all species can fly.

Only a few bird species winter in the Arctic. These include gyrfalcons, ravens, snowy owls, rock and willow ptarmigans, redpolls, and a few gull and alcid species. These species have a number of physiological and behavioral adaptations for coping with the extreme winter climate.

Snowy owls, gyrfalcons, and ptarmigans are feathered right down to their legs and feet. Ptarmigans have learned to make snow burrows, where they can ride out the weather and hide from predators. Redpolls also shelter under the snow, often living in lemming runways, where they can find seeds to eat. Ravens scavenge food around human habitation and feed on carrion and the fresh kills of polar bears and other large predators. Marine birds such as ivory gulls, dovekies, thick-billed murres, and black guillemots move to polynyas and other open areas in the sea ice, where food is readily available throughout the winter.

The rest of the arctic bird species are migrants. Each spring, millions of birds come to the tundra, taiga, and bird cliffs where they fledge a new generation before heading south again in fall. The movements of the migratory species are of great import to the people of the Far North who have specific words to mark the birds’ comings and goings. For example, in northern Alaska, April is known as kilgich tatkiat (hawks coming) and tingmirat tatkiat (geese coming), and the month of September is called tingivik (time when birds fly away).

Arctic migrants are adapted to the short period of time they have to establish territories, lay their eggs, and raise their brood. Adults typically arrive at their nesting grounds before all the snow has melted. Most have anticipated the lack of food available in early spring by fattening up at staging points on their northward migration. A migrant’s timely arrival on the breeding grounds ensures that its chicks will be born at the peak abundance of food and its young will be strong enough for the southward migration.

The migration of birds has been a point of study since the time of the ancient Greek philosophers Aristotle and Herodotus. Yet even today the secrets of migration and birds’ amazing navigational skills aren’t fully understood.

Migrating birds can cover thousands of miles in their annual travels, often traveling the same course decade after decade with little deviation. It appears evident that their migration patterns are controlled at least partially by genetic makeup. This explains why first-year birds are able to make their initial migration on their own, find their winter home without ever having seen it before, and return the following spring to the same place where they were born.

Clearly, many birds have innate navigational tools they use to orient themselves on migration. These tools are thought to incorporate responses to geographic landmarks such as seacoasts, rivers, and mountains, and to prevailing winds, barometric pressure, the earth’s magnetic field, the position of the sun, and, in the case of nocturnal migrants, the patterns of stars.

The Inuktitut word for “bird” is tingmiaq; the same word means “airplane.”

Anseriformes: Waterfowl

The order Anseriformes comprises about 150 living species of birds, all of which are web-footed and highly adapted for an aquatic lifestyle.

FAMILY ANATIDAE

GEESE, SWANS, AND DUCKS

Anatidae is a large family of birds, with 14 species of geese, 4 species of swans, and 31 species of ducks occurring in the Arctic alone. These mid-sized to large birds are distinguished by long necks, narrow pointed wings, short legs, feet with webbing between the 3 front toes, and feathers that shed water easily due to oils stored in the preen glands. Geese, swans, and ducks occupy aquatic habitats such as lakes, ponds, streams, rivers, marshes, bays, estuaries, and seacoasts. They feed on a variety of foods, including plant matter, insects, aquatic invertebrates, mollusks, crustaceans, and fish.

SUBFAMILY ANSERINAE

GEESE

Geese are relatively large birds that are colored in browns, grays, blacks, and whites. They are mostly terrestrial in their feeding habits and have strong bills adapted for grazing on grasses and other plant matter.

Most geese breed first at 2–3 years of age and typically form lifelong, monogamous pair bonds, separating only on the death of a mate. However, about 6 percent of the breeding population will “divorce,” this usually following several seasons of unsuccessful nesting. Most geese return to the area of their birth to mate and nest. The male (the gander) stands guard while the female (the goose) constructs the nest, piling up a mound of twigs, bark, and grasses, and lining the nest with soft feathers. The female alone incubates the clutch of 5–6 off-white, buff, or pale olive eggs for 28–30 days. Chicks are down-covered at birth and can feed and swim a few hours after they hatch.

Both sexes remain with the brood until the young (the goslings) fledge at about 2 months of age. The maturing period of the young overlaps with the adult’s 6-week molting period (molting is the term given to the period of flightlessness when the adults shed their outer wing feathers and regrow new ones). During this time, adults and young gather on ponds or lakes, which provide a safe resting place and security from predators. Once the chicks can fly, the family migrates as a group and often remains together until the following spring. A flock of geese flying in a V formation is called a wedge or skein. A flock of geese on the ground is called a gaggle.

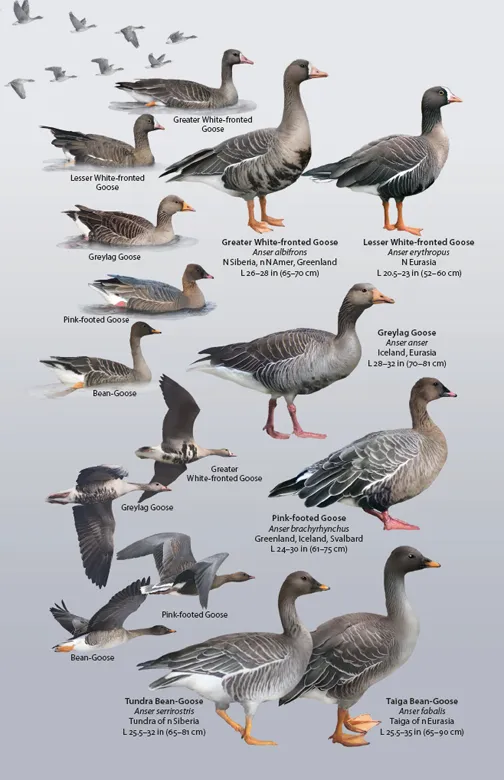

GENUS ANSER: This genus contains the gray geese, which all have grayish brown plumage, with a white undertail and white rump. The legs and bill are pink or orange.

Greylag Goose

Anser anser

ALSO: Graugans, Oie cendrée, Grågås, Серый гусь. CN refers to plumage color and habit of being one of the last species to migrate, “lagging” behind other geese. SN means “goose goose.” Ancestor of the domesticated goose. Austrian ethologist Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989) used the Greylag in his study into the behavioral phenomenon of imprinting.

RANGE: Nests (Apr–Jun) in Iceland and across Eurasia, around reed beds, floodplains, marshes, estuaries, and lakes. Icelandic breeders winter in Scotland and Ireland; Eurasian birds winter south to nw Africa and s Asia. Birds escaped from captivity have established feral populations in N Amer.

ID: L 28–32 in (70–81 cm). Grayish brown overall. Rump and back feathers edged pale gray. White line along upper flanks. Undertail coverts white. Black splotches on belly. Dull pink bill and legs. VOICE: Loud cackling or honk.

HABITS: Forages in waterside meadows and dry fields. Grazes on grass; occasionally feeds in the water on aquatic vegetation. Down-lined nest made of plant material is built on dry reeds or floating mats of sticks and aquatic plants.

Taiga Bean-Goose

Anser fabalis

ALSO: Saatgans, Oie des moissons, Ánsar campestre, Sædgås, Гуменник. SN means “bean goose,” referring to the species’ habit of grazing in bean-field stubble.

RANGE: Nests (May–Jun) from Norway and Ural Mtns east to Lake Baikal, Russia, around forest bogs, marshes, and ponds. Winters in farmlands and river valleys in w Europe, Iran, China, Japan; uncommon winter migrant to the UK.

ID: L 25.5–35 in (65–90 cm). Grayish brown. Rump and vent white. Tail gray with a white tip. Wing coverts dark brown, edged with white. Bill black at base and tip, with a yellow orange band across the middle. Orange legs and feet. Longer-necked and longer-billed than Anser serrirostris. VOICE: A groaning ung-ank.

HABITS: Feeds on green plant matter, berries, and grain crops. Nests in the open or in bushes.

Tundra Bean-Goose

Anser serrirostris

ALSO: Östliche Saatgans, Oie de la toundra, Tundrasædgås, Восточный тундровый гусь. SN means “saw-billed goose.”

RANGE: Nests (May–Jun) on the tundra of n Siberia. Winters in river valleys and around lakes in w Europe, China, and Japan. Uncommon migrant to the UK.

ID: L 25.5–32 in (65–81 cm). Dark gray, with contrasting pale breast. Pale-edged, dark brown tertials. Rump and vent white. Tail gray with a white tip. Bill black at base and tip, with a yellow orange band across the middle. Orange legs and feet. Smaller and shorter-necked than A. fabalis, with a shorter, deeper-based bill.

HABITS: Like those of Anser fabilis.

Pink-footed Goose

Anser brachyrhy...