![]()

CHAPTER 1

CONSUMPTION

PETER BEHRENS AT THE AEG AND THE LUXURY OF TECHNOLOGY

It is tempting to view Peter Behrens’s 1907–14 tenure at the Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG) as the paradigmatic example of modern architecture’s involvement with industry. The logo-emblazoned turbine factory, completed in 1909, is often described as the high point of his activities, which ranged from redesigning the AEG logo and advertising materials to the design of objects and buildings. For potential consumers of modern design, however, Behrens’s work at the AEG should be considered in the context of the sumptuous showrooms he designed in Berlin for the firm in 1910 and 1911 (fig. 1.1).

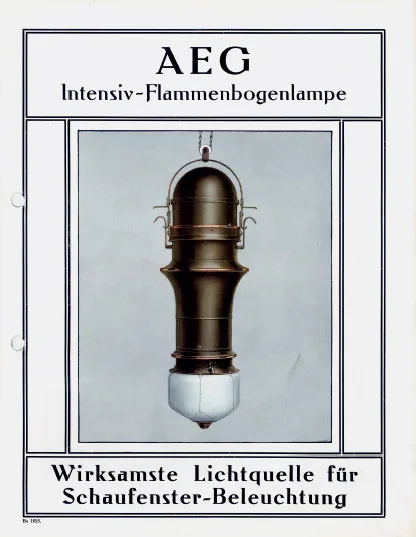

The AEG’s hiring of Behrens could not have been foretold given the trajectory of his career to that point. Originally trained as a painter, he had additionally worked as an illustrator and bookbinder in Munich. It was then that he received his first major opportunity to design on a larger scale. In 1899, the Grand Duke of Hesse invited him to join the newly founded Darmstadt Artists’ Colony, where experiments in the period’s prevailing Jugendstil were carried out by its artist members. Given the chance to design his own house and all of its contents, he was able to develop his prodigious, wide-ranging talents. He went on to direct the School of Arts and Crafts in Düsseldorf, from 1903 to 1907, and then moved to Berlin to begin work for the AEG, whose founder and general manager was Emil Rathenau. He was not hired as a direct employee, but instead served as an artistic consultant. In the same year, 1907, he helped to form the German Werkbund, a group of designers, industrialists, and politicians dedicated to improving the quality of German manufactured goods. The AEG afforded a crucial early chance to test the many ideals of Werkbund members regarding the merging of art and design with modern industrial practices, one of which was the recommendation that companies employ artists to improve their goods (figs. 1.2, 1.3, 1.4).

Behrens’s role in the promotion of modernism, however, runs deeper than the design of important factories or well-known teakettles: to be examined here are his contributions to the creation of Kauflust, or “desire to purchase,” for modern products of industry as singularly manifested in AEG shops.1 And also key is the situating of technology, especially electricity, as luxury, in relation to these products and stores.

The ground-level facade of Behrens’s first store, opened in the fall of 1910 at number 4 Königgrätzer Strasse, was sheathed almost entirely in glass. An immense floor-to-ceiling pane formed the display window, flanked to the right by a pair of glazed entrance doors with an enormous, three-paneled clerestory light above. Set in from the building’s flat plaster surface, this ensemble of windows was held by a severely beveled “frame”—an enormous, hammered sheet-copper border, edged with beading (see fig. 1.1, esp. the right side).2 Allowed to oxidize to a powdery green, this burnished frame would have contrasted with the highly polished AEG wares on display. Half-height marble panels placed at the back of the window acted as a screen, creating an interstitial display space between the street and the store’s main space, enticing pedestrians into the partly visible interior beyond it. Simultaneously, the marble panels created a serene realm for the customers within by shielding them from the commotion of the busy thoroughfare outside. Full-length silk curtains hung from the ceiling behind the window, emphasizing the great height of the space and forming a proscenium, which heightened the drama of the products on display.3 Across the top of the window, modern, sans-serif gold lettering identified the company by its full name and the subset of electrical products “for household and workshop” on “display” (Ausstellung für Haushalt und Werkstatt).4 To the right of the window, the entrance door featured the famous hexagonal logo with the company’s initials, which were also painted on the three panes of its oversized light.5 The logo on the door is the only eye-level indicator of the store’s identity; all other text, placed high up on the glass panes, directed the viewer’s attention to the entirety of the store’s facade. This assemblage of text, floor-to-ceiling drapes, and plate glass especially emphasized the soaring height of the space, and yet, along with the frame, confined and encapsulated it, directing attention toward the gleaming goods on display.

Inside, smart leather club chairs set in mirror-glass niches were interspersed between shiny metal and glass vitrines and side tables (fig. 1.5). The upper white walls, topped by exaggerated dentils over the niches, added an element of reserved classicism to the opulent modernism of the interior. On the ceiling, bare bulbs simply set in shiny metal sockets emphasized the store’s intent—an interior designed to sell modern products, but also to celebrate industry and technology.

For the second store, which opened in the spring of 1911 at 117 Potsdamer Strasse, Behrens again employed a combination of traditional and sumptuous modern materials (fig. 1.6). A vocabulary of even more stripped-down forms and a greater emphasis on flat surfaces distinguished this store. Framed by monolithic, lightly veined, white marble slabs on three sides, the storefront was a simple portal beckoning in the affluent consumer. Chiseled on the marble like a Roman epitaph, the company name and a list of its most important products was inscribed in clear, elegant typography. Each of these marble slabs was surmounted by a faintly projecting cornice of green marble resting on a richly veined plinth of the same material. The door and the window frames were painted green, resulting in a unified, tasteful ensemble.6 Deeply set in the store’s marble proscenium was a tall, narrow entrance door crowned by a beveled clerestory window and a large plate glass display window. At the very bottom of the window, on low white plinths and shelving, Behrens placed an array of small, shiny AEG products; they twinkled like jewels, dwarfed by the majesty of this white marble proscenium. This green-and-white scheme with its rectilinear use of flat marble also stylistically connected this store with commissions Behrens executed just prior to it, namely, the early Christian–style AEG pavilion for the German Shipbuilding Exhibition in Berlin (1908), the early Florentine Renaissance–style pavilion designed for the Northwest German Art Exhibition in Oldenburg (1905), and a crematorium in Hagen (1905–8). The latter two buildings both show the influence of San Miniato in Florence, and they both feature a round, beveled clerestory window, in addition to similarities in materials and color. Working in a pared-down, modern idiom, Behrens nevertheless connected his buildings, and the products he designed for the AEG, to the representative grandeur and elegance of previous stylistic periods.

Figure 1.1. Peter Behrens, AEG store, 4 Königgrätzer Strasse, Berlin, 1910.

Figure 1.2. Behrens, AEG teakettles, 1909.

Figure 1.3 Behrens, AEG fan, 1914.

Figure 1.4 Behrens, AEG arc lamp, 1908. Advertisement, 1912.

Inside the store, Behrens deployed architectural elements and rich materials to evoke a luxurious world into which AEG goods were to be placed. Immediately upon entering, visitors encountered a rich, generously sized brown leather sofa set into a niche of geometrically paneled cabinetry in dark wood (fig. 1.7). A built-in, horizontal vitrine extended the length of the salesroom; installed at eye level, its parade of objects would have immediately caught the attention of potential buyers entering the store. Above the vitrine, punctuated only by a large AEG wall clock, dark green, patterned wallpaper ran to the ceiling.7 As in Behrens’s first store, classical elements are utilized in conjunction with restrained modernism. Here the dentils are more diminutive, ringing the square coffers, each of which features a single light bulb set into a bare metal holder. In both stores, then, recognizable, tasteful classical forms and materials (coffers, dentils, plinths, marble) were carefully combined with the materials and elements of industry (glass, metal, light bulbs, electricity).

Thus the visual vocabulary of these two select, high-visibility shops—with their ample plate glass, and spare, repetitive elements—represented key visual and material aspects of modernism. But they went further than merely visually and materially representing modernism’s ideals. Indeed, as early as 1911, observers commented on the stores’ overall sachlich, or spare, qualities and on their eliciting a sense of consumer desire. In selling modern technology, the AEG enlisted visual design and modern architecture in the endeavor of commodification. The carefully conceived stores were among the places where the company did so, representing an early and select method by which industry displayed and sold modernism to the public.

Figure 1.5. Behrens, AEG store, main showroom, 4 Königgrätzer Strasse, Berlin, 1910.

Figure 1.6. Behrens, AEG store, 117 Potsdamer Strasse, Berlin, 1911.

Exhibited in Behrens’s modern stores, AEG products were staged to spur consumption by invoking a luxurious—and for most, elusive—world enhanced by modern technology and electricity (see fig. 1.5). For many modernists, and for companies that subscribed to modernism, creating consumer desire became a crucial goal of widening the audience for its machine mass-produced objects. The company could have elected to produce its objects more cheaply. Instead, the AEG did not market its electrical goods as advanced technology or rationalized, functional products. Rather, the firm displayed and sold its goods as alluring, even lavish, domestic objects. This has larger implications for a new understanding of the way that modern objects and architecture were conceptualized and sold in the period. In the words of Peter Jessen, a prominent German Werkbund member writing in 1912, Behrens’s entire body of work at the AEG represented “a single spirit of true modernity.”8 Behrens’s oeuvre has long been viewed in this unifying capacity. Examining the stores and the goods on display brings some much-needed complexity back into the picture, for they functioned as a crucial intermediary between the elite world of modern design with its theory, practitioners, materials, and alignment with industry and actual consumers. A key characteristic of the AEG’s consumers is that they came very largely from affluent circles. As forerunners to the broader public that modernism aspired to transform, these buyers had to be convinced to consume modern products. Evoking a sumptuous world, the stores showcased the products and conjured the luxurious modern environments for which they were intended. They were aimed at the affluent consumers that the AEG sought to woo, and window-shoppers at large.

Figure 1.7. Behrens, AEG store, main showroom, 117 Potsdamer Strasse, Berlin, 1911.

THE CIRCUIT OF LUXURY: ELECTRICITY AND ITS CONSUMERS

At the end of the nineteenth century, electricity itself was a privileged, urban phenomenon, which had long been linked to luxury in the public eye because it had been used to illuminate important, preeminent shopping and public streets of cities. The cleaning of the street’s arc lamps on Unter den Linden in Berlin, the great public boulevard, was a public spectacle.9 In Germany, from its earliest availability, electricity had been generally confined to public ...