- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Media images shape and are shaped by society. They reflect the ways in which the social order changes and stays the same. The contributors to Gender and the Media: Women's Places consider a variety of media to explore the impact of what is there, as well as what is missing. Their focus is on women. Networks of the cyberbullying of women of color are rendered graphically and the agency claimed by women in Western Sahara refugee camps is shown in photos. How college women and men respond to the masculinity reflected in hip-hop lyrics and videos, and what it feels like to be a woman in a comic book store are conveyed in excerpts from interviews. Contributors detail how publications discuss rape in India and trafficking in Moldova and ponder the absence of the topic of anorexia in U.S. cinema. Social change is reflected in how trade publications discuss the increasing number of women in the funeral industry. The relation of the local to the global and female invisibility is considered in an analysis of Portuguese punk fanzines. An examination of advice books for American tween girls documents not only the subject matter, but also the racial, ethnic and religious homogeneity and heteronormativity assumed in the text and illustrations. Finally, a comparison of the critical response to identical music recorded by female and male artists provides the opportunity to see the role gender plays in criticism of aesthetic materials.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

AGENCY AFFIRMING PLACES

CHAPTER 1

WAR, CULTURE, AND AGENCY AMONG SAHRAWI WOMEN REFUGEES: A PHOTO-ESSAY

ABSTRACT

In Hassani culture, women play the most important role in the family. Hassani women hold high positions of power and authority not only within their family, but also in their community and nation. Hassani women have played an essential role in building community in the refugee camps in Southwest Algeria to which they fled during the Western Sahara War in 1976.

Keywords: Hassani culture; Western Sahara; Arab women; visual anthropology; refugee; agency

PHOTO-ESSAY

Western Sahara is a disputed territory in the Maghreb region of North Africa, which has been partially controlled since 1975 by both Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). Since 1973, the Popular Front of Liberation of Saguiat el Hamra and Rio de Oro (POLISARIO) – which officially represents the Sahrawi population and government, located in refugee camps in Tinduf Algeria – has engaged in an armed struggle to free that territory: first from Spain which protected and administered it from the time of the Franco-Spanish convention (1884–1976), then from Morocco and Mauritania, to which Spain transferred its administrative powers by the Madrid Accords of 1975 (Lippert, 1992) (Fig. 1).

In this photo-essay I argue the importance of analyzing Arab women within their local context, rather than through colonialist tropes – contrasting them to modern liberated western women. This oversimplified portrayal is often based on common stereotypes, which Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (2013) describe as “fixtures in the stylistic landscape” (p. 250). This essentialist narrative was employed initially by imperialist photographers to portray Arab women as either uncovered sensual and seductive belly dancers, or covered anonymous, submissive, and oppressed. These stereotypes continue to be perpetuated by various other mediums, photography included.

I argue for the recognition of the rich diversity of Arab women, with a focus on the experiences of Sahrawi women, as their sartorial move is not made in a vacuum or in global western context – it is a native style reflecting a native identity. As Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (2013) note, “When we talk about style, we are talking about a process that connects combinations of elements of behavior with social meaning” (p. 264). Sahrawi women and men living in refugee camps in the harsh desert of Southwest Algeria have, for 40 years, resisted the Moroccan colony through their dress, food, poetry, and maintenance of their Hassani culture. With their traditional dress, Sahrawi women are performing their identity, one which is “licensed for their bodies and their ethnicity” (p. 265).

Fig. 1. Western Sahara. Source: Wikimedia.org.

This photo-essay portraying Sahrawi women is a result of ethnographic research using photography as a research method. These images are the product of observation that was organized during my stay in various Western Sahara camps in December 2016, documenting the life of the Hassani matriarchal community. My approach draws upon my active participation – living in Sahrawi refugee camps – and depends on a realist interpretation of still (which I present here) and moving images.

Developments in gender theory have had an important impact on ethnographic methodology since the 1990s. Researchers and theorists began to explore how the gendered self is never fully defined in any absolute way and how the gender identity of an individual comes in to being in relation to the negotiations that it undertakes with other individuals. Sarah Pink (2001) argues that “if visual images and technologies are part of the research project, they will play a role in how both researcher and informant identities are constructed and interpreted” (p. 21). Photography served me as a way to initiate my research in the camps – a “can-opener” as it is called by Collier and Collier (1986) – to establish rapport with my informants. For security reasons mobility inside the camps and between them was very limited and only allowed within the company of an authorized person. As a female Arab researcher with a camera I was perceived as a reporter and a photojournalist that put me in an ideal position to observe Hassani culture in the camp. The camera played an important role allowing me more mobility and access. I was invited to different events in the camp: protests, political gatherings, training and workshops, family celebrations, school events, and every activity happening in the camp, which gave me access to the larger community rather than just to the people I lived with (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2. Bojador is one of the five wilayas (districts) of the refugee camps.

Fig. 3. Smara is one of the five wilayas (districts) of the refugee camps.

Before I describe modern-day Saharawi women in the refugee camp of Jarash, I would like to summarize the history of the conflict, as well as how Hassani culture has resisted the Moroccan occupation. In particular, I will discuss women’s multifaceted role in the community prior to and after the Sahrawi conflict.

The Western Sahara conflict labelled “Africa’s last colony” (Jense, 2005) and the “forgotten conflict of the 21st century” is understudied, especially considering the political transformations and revolutionary activity that took place in the rest of the Middle East and North African regions. The Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria have garnered the most scholarly attention over the last several years. Historically, academic scholarship on this region has largely focused on its history, starting from Spanish colonization and critiquing the failure of the United Nations to create a successful referendum. Scholars have also been interested in examining the culture, gender, and identity of the Sahrawi people living in refugee camps.

Sahrawi are Hassani indigenous nomadic people of mixed Arab–Berber descent. In Bedouin tradition women and men are considered equal. Traditionally, women manage and maintain the community, given the nature of men’s role in herding camels and goats outside of their settlement. When the Western Sahara War started, most men, aside from elders and children, joined the battlefront and women took up the responsibility for making, repairing, and moving the tents and participating in major tribal decisions. The importance of Sahrawi women in the camps grew exponentially during this war. San Martín (2010) thoroughly explains the roles of women within the refugee camps during this time: she describes this female-dominated structure within the refugee camps as a society where all Sahrawis are “working together as equals,” consequently multiplying their chances of achieving a just and independent state.

In 1974, the POLISARIO front created the National Union of Sahrawi Women (NUSW) as the people’s organization of all women of the SADR. Today NUSW (2018), claims to have 10,000 members, primarily active not only in the refugee camps but also in the occupied territories and the diaspora. Under NUSW, women are responsible for the camp’s administration and functioning. They are involved in education and training, health, food distribution, justice, and socio-political issues. They hold positions of power and authority as leaders in the struggle for independence from Moroccan occupation and as representatives of the democratic process. As these women are in the highest positions in Hassani society, they influence local and national policies.

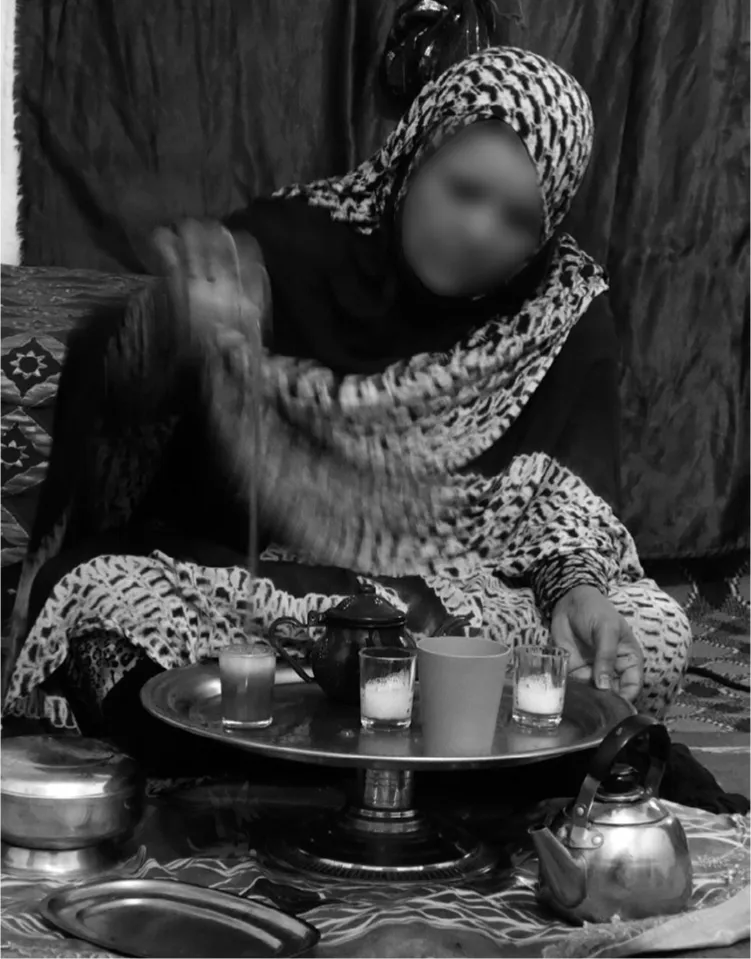

This photo-essay, portraying Western Sahara women, challenges the myth of helpless and vulnerable Arab-Muslim women, especially during situations of conflict and displacement (Figs. 4–18).

The case of Western Sahara women counters the common misconception of Arab-Muslim women as oppressed and powerless. I believe the political situation of the nation has been a significant opportunity for Hassani woman’s development and the strengthening of her role in the society.

When studying gender issues in the Arab world it is important to include comprehensive and historically contextualized analysis for each country. Countries in the Arab world are complex and culturally very diverse, manifested in multiple dimensions: ethnic, tribal, religious, and linguistic.

Continuing to dilute the identities of Arab-Muslim women, especially through out-of-context comparisons to western expectation, is not only damaging to this culture, but also fails to credit the impact these women have in their community and nation as well as on peace negotiations and conflict resolution, specifically when it comes to Western Sahara women (Fig. 19).

Fig. 4. Training organized by nusw. Online workshops presented by scholars and gender specialists from spain university.

Fig. 5. The sense of community is very strong in the camps. This woman refugee goes out every now and then to offer candies to kids, a role she chose to fulfil in order to stay connected to the rest of her community.

Fig. 6. Food, drinking water, building materials, and clothing are brought by international aid agencies to camp (unhcr). Local committees of women organize and manage distribution of these goods.

Fig. 7. With the help of the children of the family i lived with we went to collect cleaning products from the woman who is in charge.

Fig. 8. Refugees are waiting with their empty propane tanks for refill. Propane is used for cooking and heating water.

Fig. 9. Weddings are one of the most important celebrations for sahrawis refugees. It is one of the few entertainments at the camp. The bride is leading a large gathering of women at the beginning of her wedding ceremony as the band (male) plays music.

Fig. 10. The bridal family (the bride’s brother with the white scarf and his friend opposite) is serving camel milk to guests – a sign of luxury and wealth.

Fig. 11. Tea is a traditional drink for hassanis. Tea is prepared daily, starting from breakfast. The ritual is to serve three times in a row, every time a tea is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Women’s Places: An Introduction to Gender and the Media

- Part I Agency Affirming Places

- Part II Overtly Hostile or Agency-Denying Places

- Part III Covertly Negating Places

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Gender and the Media by Marcia Texler Segal,Vasilikie (Vicky) Demos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.