![]()

ISLAM AND THE MILLENNIUM

THIS BOOK brings into dialogue two major fields of scholarship that are rarely studied together: sacred kingship and sainthood in Islam. In doing so, it offers an original perspective on both. In historical terms, the focus here is on the Mughal empire in sixteenth-century India and its antecedents and parallels in Timurid Central Asia and Safavid Iran.1 These interconnected milieus offer an ideal window to explore and rethink the relationship between Muslim kingship and sainthood. For it was here that Muslim rulers came to express their sovereignty and embody their sacrality in the manner of Sufi saints and holy saviors.

The Mughal dynasty of India (1526–1857) and the Safavid one of Iran (1501–1722) exemplified this mode of sacred kingship. The early and foundational monarchs of these two lineages modeled their courts on the pattern of Sufi orders and fashioned themselves as the promised messiah. In their classical phases, both the Mughals and the Safavids embraced a style of sovereignty that was “saintly” and “messianic.” Neither a coincidence nor a passing curiosity, this similarity resulted from a common pattern of monarchy based upon Sufi and millennial motifs. There developed in this period an ensemble of rituals and knowledges to make the body of the king sacred and to cast it in the mold of a prophesied savior, a figure who would set right the unbearable order of things and inaugurate a new era of peace and justice—the new millennium. Undergirded by messianic conceptions and rationalized by political astrology, this style of sovereignty attempted to bind courtiers and soldiers to the monarch as both spiritual guide and material lord.

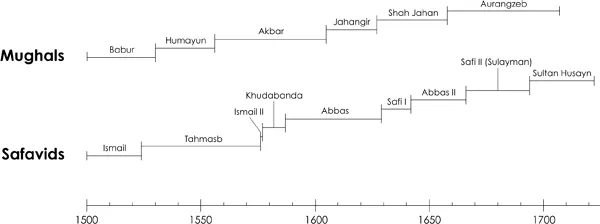

The most famous case of such an attempt is that of the powerful Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605). As the epitome of this mode of sacred kingship, he not only established a lasting empire in South Asia of unrivaled grandeur but also fashioned himself as the spiritual guide of all his subjects regardless of caste or creed. At the height of his reign, Akbar was accused of declaring the end of Islam and the beginning of his own sacred dispensation. There was some substance behind these accusations. Akbar had unveiled a devotional order in which his nobles and officers of all religious and ethnic stripes were encouraged to enroll as disciples. Although not given an official name, this institution of imperial discipleship (muridi) became known as the Divine Religion (Din-i Ilahi). It generated an immense controversy—a controversy, it can be said, of global proportions. Reports and rumors of how a great Muslim emperor had turned against Islam were followed with interest in Shii Iran, Sunni Transoxania, and Catholic Portugal and Spain. Akbar was accused of heresy, schism, and apostasy from Islam. He was charged with claiming to be a new prophet and even a divinity descended to earth. Despite the outcry and criticism, however, Akbar’s rule flourished in India, and his circle of devotees thrived. Discipleship became a Mughal imperial institution under Akbar and evolved after him. FIGURE 1.1 Mughal and Safavid rulers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Unsurprisingly, Akbar’s spiritual pursuits became the focus of numerous studies in modern times. All manner of explanations—political, psychological, and spiritual—were used to make sense of the Mughal emperor’s religious experiments. Although these studies differed in method and conclusion, they had one trait in common: they utilized a framework of analysis that was limited to Akbar’s India. Whether these studies treated this episode as an eccentricity of the emperor’s personality or saw it as a Muslim ruler’s radically liberal and precociously secular attempt at a tolerant religious policy, they generally agreed that it was a phenomenon particular to Akbar’s reign and dominion. In other words, the manner in which the emperor’s sacrality was enunciated and institutionalized was assumed to have neither history nor comparison.

This assumption becomes untenable, however, when we examine the forms and timing of the Mughal emperor’s sacred assertions. Akbar had claimed to be the world’s greatest sovereign and spiritual guide at the turn of the Islamic millennium. He had fashioned his imperial self, in effect, in the mold of the awaited messiah. In doing so, he had embraced a powerful and pervasive myth of sovereignty. It was widely expected that the millennial moment heralded a grand change in the religious and political affairs of the world. A holy savior would manifest himself, it was thought, to usher in a new earthly order and cycle of time—perhaps the last historical era before the end of the world. In his pursuit of sacred sovereignty, Akbar was neither the first nor the only one to pour his sovereign self into such a messianic mold. He had competed for the millennial prize with many others. Indeed, the emperor’s critics considered his spiritual pretensions to be far from original. On the contrary, they accused him of trying to mimic the messianic success of the founder of the Safavid empire in Iran, Shah Ismail (r. 1501–1524). When not yet in his teens, Shah Ismail had become the hereditary leader of the Safavid Sufi order in northwestern Iran. With the aid of armed and fanatically loyal Turkmen devotees, he had conquered and reunited Iran after more than a century of fragmentary politics. Shah Ismail’s soldier-disciples charged into battle, it was said, without armor, because they expected their saint-king’s presence to provide sufficient protection. The young shah was for them the promised messiah—the mahdi of Islamic traditions. That Akbar’s millennial project in India evoked comparisons with Shah Ismail’s militant messianism in Iran is indicative of a strong similarity between the two enduring Muslim empires of sixteenth-century Iran and India. It brings into focus the startling fact that both Islamic polities, in their formative phases, had seriously engaged with messianic and saintly forms of sovereignty. This similarity, importantly, was not a coincidence but the result of a shared history. The imperial projects of the Mughals and the Safavids in the first half of the sixteenth century had competed for the same set of material resources, patronage and kinship networks, and cultural symbols. Akbar’s Timurid father and grandfather, Humayun and Babur, had both sought refuge and military assistance from the Safavids at low points in their royal careers and had witnessed the workings of the Safavid court and Sufi organization up close. The Safavids, in turn, had adopted the highly stylized forms and fashions of the latter-era Timurid courts as they evolved from a Sufi order into an imperial dynasty. The two nascent sixteenth-century empires had drawn upon a shared cultural context and learned from the other’s modes and methods. It was no accident that in both these polities a similar style of monarchy developed, in which claims of political power became inseparable from claims of saintly status.

More generally, this conjuncture of kingship and sainthood was a product of recent historical development. It first took root in and spread from the geographical territories of Iran and Central Asia that had been ravaged by the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century. These invasions had severely disrupted established urban centers, political cultures, and religious associations across much of Muslim Asia. In their wake, a new sociopolitical order took shape, in which the growing networks of Sufi orders and Sufi shrines played a significant and constitutive role. There was hardly an aspect of public or private life in the eastern Islamic lands that remained untouched by these institutions of “mysticism” and networks of “devotion.” The lives of kings were no exception. Thus, in the post-Mongol centuries, the institution of kingship became locked in a mimetic embrace with the institution of sainthood.

Unsurprisingly, then, the greatest of Muslim sovereigns of the time began to enjoy the miraculous reputations of the greatest of saints. Some, like the famous conqueror Timur (or Tamerlane, d. 1405), from whom the Mughals traced their descent, may not have made such claims openly, but they were, nevertheless, venerated as spiritual guides by their followers and given miraculous genealogies by their descendants. Others, like the Safavid Shah Ismail, already belonged to acclaimed Sufi families. Indeed, Shah Ismail had been born a saint in the sense that he had inherited the devotion of his father’s large circle of disciples. It would be wrong to suggest, however, that these Muslim sovereigns assumed the trappings of saintly piety and renounced the world and its sinful ways. More accurately, they adopted the trappings of saintly power and embraced the world as heaven-sent saviors. The “messianic” and “saintly” nature of their sovereignty was adduced by astrological calculations and mystical lore, embodied in court rituals and dress, visualized in painting, enshrined in architecture, and institutionalized in cults of devotion and bodily submission to the monarch as both saint and king. Why then, one may ask, has modern scholarship had difficulty seeing the coherency and durability of this pattern of sacred kingship in Islam? The answer in simplest terms is that Sufism and Muslim kingship have been studied mostly in a bifurcated fashion, the former in religious studies and the latter in political history. The differences in approach and method between the two disciplines have led to Sufis and kings being conceived and portrayed in opposing spheres of culture, the one sacred and the other profane. It has also led to a model of religion and politics within Muslim societies that is too formal and textual, giving too much weight to doctrine and not enough to practice. Approaches adhering to this model are bound to dismiss a Muslim king’s spiritual assertions as besotted and idiosyncratic. Similarly, they are constrained to see a Sufi mystic’s claim to material power as unrelated to his saintly endeavors. Such constraints must be overcome, however, to make sense of a milieu in which mystics and monarchs were collaborators and competitors. Indeed, in early modern India and Iran, royal and saintly families intermarried and patronized one another. Sufi tutors educated princes, and scions of saints served as imperial generals. Queens were sent to the homes of mystics to give birth, and saintly shrines were constructed inside palace walls. Hereditary cults and dynastic lines became, in effect, physically intertwined and materially blurred as the courts and shrines in Iran and India came to adopt the same repertoire of sacrality and style of sovereignty.

Admittedly, from the pious and well-worn perspectives of Islamic law and political theory, the phenomenon of Muslim kings transmuting into saints and messiahs venerated by courtiers and worshipped by soldiers seems markedly heretical and transgressive, not to mention paradoxical. Conventional views of Islam would have Muslim sovereigns always looking to the ulama and using doctrinal notions of the caliphate to legitimize their rule. This book challenges such conventional wisdom by emphasizing, instead, the performative aspect of Muslim kingship. Rather than turn to abstract legal, philosophical, and ethical writings, it constructs the cultural logic of sacred kingship from the concrete acts of rulers, which were often performed publicly in a competition for popular admiration and awe.

While the texts and traditions of doctrinal Islam continued to be patronized in this milieu in a routine enough manner, they did not serve as the fount of charismatic inspiration. Inspiration came from a source that was surprisingly different and, on the face of it, paradoxical: “heretical” conceptions of sacred authority attracted a Muslim sovereign more than “orthodox” notions of Islam. A substantial part of this study is dedicated to resolving this paradox. It does so by giving ritual practice and performance an interpretive priority over religious doctrine and law. For what may appear as “heresy” from a doctrinal point of view was, in many cases, a ritual engagement with popular forms of saintliness and embodied forms of sacrality that were broadly and intuitively accepted by much of the populace as morally valid and spiritually potent. To make way for this perspective, however, we must set aside many conventional assumptions and timeless truths about Islam. Instead, we must examine from first principles the social processes that transmuted kings into saints and saints into kings. To appreciate how such phenomena could occur in “Islam,” we must first grasp the significance of the “millennium.”

ISLAM AND THE MILLENNIUM

In most studies of Muslim milieus, group identities of sect, doctrine, and devotional loyalty are assumed to be more fixed and hegemonic than they historically were. For example, the Mughals of India are treated as Sunni Muslims, as are their Central Asian Timurid ancestors.2 When the Safavids are compared with the Mughals, the former are assumed to be Shii Muslims.3 If an element of commonality is assumed between these two dynasties, it is ascribed to the “mystical” practices of Sufism. This intellectualist view of Islam neatly divided into Sunnism and Shiism, with Sufis...