![]()

1 STRANGERS IN THE CITY

Behind the grand domes and palaces of Genoa, I could see the mountains still. Apricale wasn’t far away, just there, behind that second hill, where that tree is bending slightly in the wind. I grew up there, in dark cobbled streets with hundreds of corners and crannies where we could hide and play, along with the cats. There must have been a million cats in the village. You looked up and it seemed as if God had opened his hands and dropped the houses onto the hilltop and that they had tumbled down and stopped at crazy angles. We had our fields, my dad and I, up above the village, looking down. Some mornings you could hardly breathe when you got up there, particularly on winter mornings, when the wind was cold and the sun froze you in its light. But when my dad died, things changed.

The ship is moving now. I can hardly see. There are so many of us on deck watching, weeping, blinking so that the image of those mountains stays printed on the inside of our eyelids and we can take it with us to where we’re going. Wherever that is. That man on the foredeck with the captain, the one in the frock coat and the top hat with a blue and white sash, he knows. He’s the one who found us, who told us that on the other side of the world was a country waiting for us. There was land there. There were empty farms with houses that we could live in – the keys were above the door, ready for us. It was so vast, this place, that we would have to board a train and travel a day and a night. But first they would give us a room in a hotel, and food. And they would welcome us.

I can hardly see my hills now. I can see Genoa, disappearing into the mist. Everyone is crying now, waving – but who to? Who knows how long it will be before we come back here, to Liguria. Perhaps we will come back with new families, and perhaps we will travel in the cabins, with the gentlemen. Perhaps?

IMMIGRANTS

In 1869, Buenos Aires had 223,000 inhabitants. A single generation later, in 1914, it was the largest city in the hemisphere after New York, with a population of just over 2 million. Most dramatically, nearly 48 per cent of the city’s inhabitants were foreign born. Buenos Aires had been transformed in these few years ‘from a riverside town to a modern metropolis’.1

The city had not only changed in size in those years; it had become profoundly cosmopolitan, diverse, home to a variety of languages and cultures. And at the same time, a yawning gulf had opened up between the old city centre and the wealthy suburbs, with their elegant, well-heeled residents, and the districts around the expanding port. Here was the melting pot in which the new city was being forged.

Who were these new arrivals, these builders of the new Buenos Aires? And why had they been encouraged to come?

By the mid-1860s, the conflict that had divided Argentina since it declared independence from Spain in 1816 had been resolved. The debate about the future of the newly independent republic centred on one question. Would the country develop through its trade with the rest of Latin America, diversifying its economy as it went; or would it throw in its lot with the foreign traders (particularly the British) and grow by exporting its meat and agricultural products, exchanging them for consumer goods and manufactures imported from Europe? Each alternative carried its own political programme and its own ideology. In one case, the logic pointed in the direction of Latin American cooperation and unity, a kind of continental nationalism. In the other, Argentina would continue to be dependent on European colonial powers, and prosper as a result of that relationship.2

The then President of Argentina, Bartolome Mitre, a member of the wealthy landowning aristocracy whose large estates produced the goods to be exported, threw open the doors of the Argentine economy and invited foreign, but especially British investors, to put their money into the expanding meat and cereal production of his country. They took up the opportunity enthusiastically and the country moved into a new chapter in its history. The market for Argentine mutton and lamb, and its wheat, grew dramatically.

Had the plan to connect with Latin America borne fruit, the centre of the country might have been established elsewhere, in the wealthy area of Corrientes, for example. But the focus on European trade carried with it one inevitable consequence: Buenos Aires would become the heart of an independent Argentina, its port the crossroads through which all commerce passed.

And there was another expression of the triumph of the European connection; a dominant idea that progress would only be possible with the adoption of European ideas, values and behaviours – in a word, European ‘civilization’. In the 1840s, two writers had given form to this view. Alberdi’s slogan ‘To civilize is to populate’ became a kind of watchword. And the literary representation of that idea came in the form of a book, part novel part sociological treatise, written by a vigorous advocate of the European connection: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.

Facundo (1845) recounted the life of one of the more notorious local chieftains on the vast Argentine prairies, the

pampas.3 He was represented as a kind of primitive, driven solely by instinct and expressing the realities of a violent

world without moral or social values. Oh, they were fine horsemen, these cowboys or

gauchos, who followed their horses and cattle back and forth across the Argentine

pampas. And they were free, in the way that wild animals are free. But theirs was a natural instinct that had to be tamed, if Argentina was to become the civilized nation Sarmiento and his circle imagined. Natural man must be replaced by civilized man. In another sense, Latin American man – so close to the world of instinct and so far from the social skills indispensable for the new Argentina – had to be re-educated, forcibly if necessary. And it was not only a matter of dealing with particular individuals and their characteristics, but of eliminating the way of life which, in Sarmiento’s view, inevitably produced and reproduced the Facundos of Argentine history.

In practice, this connected perfectly with the enclosure of the pampas, which until then were common lands grazed freely by the independent gauchos who moved with their herds. With their disappearance, the pampas could be fenced and divided into the great estates (or estancias) which would increasingly be devoted to producing the rich red beef for which Argentina would become justly renowned.4

The necessity for immigrant labour had already been anticipated in the 1852 Constitution, that set out a surprisingly liberal policy on immigration to the new Argentina:

The Federal Government will encourage European immigration, and it will not restrict, limit or burden with any taxes the entrance into Argentine territory of foreigners who come with the goal of working the land, improving the industries and teach the sciences and the arts.

But the fact that this was more than a question of expanding the labour market is signalled in the second part of this clause. For these were immigrants who would come ‘to improve and to teach’. In other words, they were already seen as the physical embodiment, the bearers of that European civilization which would transform and modernize Argentina in a single generation.

Mitre had already invited European investors to collaborate in national development in the 1850s. Now, in the late 1860s, the invitation was extended, actively, to Europe’s peasant farmers and workers. And the city that would receive them, the riverside town that was fast becoming a capital city and a major port – Buenos Aires – made ready to receive them.

It is unclear whether the governments of the day had thought through how the immigrant population would live, especially given the scale of the process. Perhaps they envisaged an effortless absorption. In any event, the self-confidence of Argentina’s wealthy classes was at its height as the immigrant ships arrived in numbers in the early 1870s. The reason? The outcome of the war with Paraguay, known as the War of the Triple Alliance.5

Paraguay in 1865 was an isolated but expanding economy under the absolute control of the dictator López. Landlocked as it was, in the upper reaches of the Paraná River, the compelling need for a direct outlet to the sea for its exports led to a confrontation with Brazil and Argentina, its far larger and more powerful neighbours (Uruguay was the third and much smaller partner in the alliance). Despite its well-prepared and larger military forces, Paraguay’s defeat was devastating. Some 60 per cent of its population (predominantly the men) died in the five years of the conflict! For Brazil and Argentina, the considerable spoils of war were the newly conquered lands, fertile but sparsely populated, of the Gran Chaco, where yerba mate – once Paraguay’s main export – grew in abundance.

Argentina was already an important agricultural country before the war; together with Brazil, it was the largest economy on the continent. The trade in wheat, dried meat and leather was growing apace, as it had done ever since the country had broken free of its Spanish colonial masters and their monopoly on trade in 1816. Ironically, war had been a highly profitable time for the landowners of the Argentine province of Corrientes, who supplied meat and cereals to all three armies. Argentina’s newly acquired 20,000 or so square hectares of land added to its potential wealth, and made it an even more attractive proposition for foreign investors. In fact, between 1860 and 1913, Argentina received 8.5 per cent of the world total of direct foreign investment. And it was Britain that emerged as the largest direct beneficiary of the war, having financed Brazilian armaments, provided war loans to Paraguay and expanded its trade with the Argentines.6

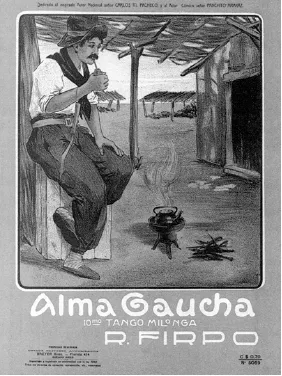

THE LAST GAUCHO: THE STORY OF MARTIN FIERRO

‘Martin Fierro’, the central character of a long epic poem written in two parts (1872 and 1879) by José Hernández,7 came to represent those generations of skilled horsemen and herders who for centuries occupied the great grasslands south and west of Buenos Aires called the pampas. They were independent and individualistic, their lives a series of nomadic journeys across the pampas, moving their animals in search of pasture, gathering in small communities in settlements rarely containing much more than some makeshift dwellings, a bar and a shop. The work was hard and unforgiving, the culture masculine and brutal. They would gather around camp fires and while they waited for meat to roast, share experiences through the songs and stories passed on from generation to generation, accompanied by the strange seven-string guitar called the vihuela. These stories were the myths of a restless population riding the common lands.

My greatest joy is living free

Like a bird in the open sky

I never stop to build a nest

There’s nowhere free of pain

But no-one here can follow me

When I take wing and fly.

And I want you all to understand

When I tell you my sorry tale

That I’ll only fight or kill a man

When there’s nowhere else to go

And that only the actions of others

Set me on this wretched path.

Over time there emerged regional chieftains or ‘caudillos’, with their own bands of horsemen mobilized in the battle for territories of control. Some caudillos became powerful and influential, though they rarely abandoned the characteristic dress and manner of the gaucho: the wide trousers tucked into leather boots, the short poncho and the leather hat.

By the time Martin Fierro came into being, the gaucho way of life, derided by Sarmiento as a brutalizing instinctual existence without morality, violent, arbitrary and short, was in its final moments. The pampas were no longer common lands; they were fenced and divided among the landowners whose animals would later find their way to the slaughterhouses of Buenos Aires and thence make their way to Europe or the United States. As this process of enclosure continued, the gauchos were driven to the margins of the prairie, and often were recruited, as Martin was, to pursue the war of exterminat...