eBook - ePub

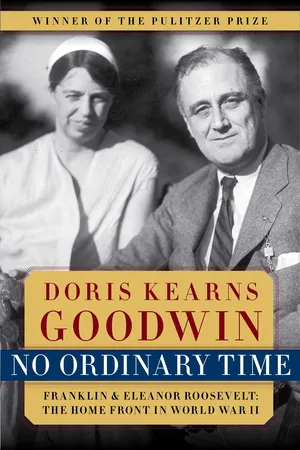

No Ordinary Time

Franklin & Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II

This is a test

- 768 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Doris Kearns Goodwin's Pulitzer Prize–winning classic about the relationship between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt, and how it shaped the nation while steering it through the Great Depression and the outset of World War II. With an extraordinary collection of details, Goodwin masterfully weaves together a striking number of story lines—Eleanor and Franklin's marriage and remarkable partnership, Eleanor's life as First Lady, and FDR's White House and its impact on America as well as on a world at war. Goodwin effectively melds these details and stories into an unforgettable and intimate portrait of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt and of the time during which a new, modern America was born.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access No Ordinary Time by Doris Kearns Goodwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

“THE DECISIVE HOUR HAS COME”

On nights filled with tension and concern, Franklin Roosevelt performed a ritual that helped him to fall asleep. He would close his eyes and imagine himself at Hyde Park as a boy, standing with his sled in the snow atop the steep hill that stretched from the south porch of his home to the wooded bluffs of the Hudson River far below. As he accelerated down the hill, he maneuvered each familiar curve with perfect skill until he reached the bottom, whereupon, pulling his sled behind him, he started slowly back up until he reached the top, where he would once more begin his descent. Again and again he replayed this remembered scene in his mind, obliterating his awareness of the shrunken legs inert beneath the sheets, undoing the knowledge that he would never climb a hill or even walk on his own power again. Thus liberating himself from his paralysis through an act of imaginative will, the president of the United States would fall asleep.

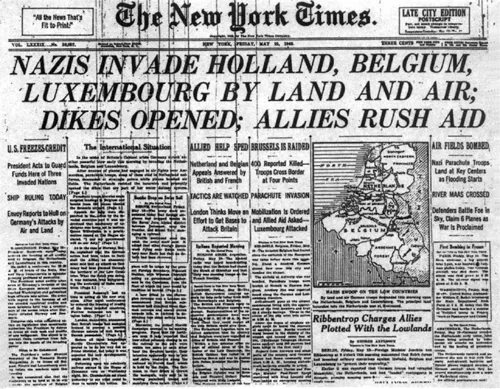

The evening of May 9, 1940, was one of these nights. At 11 p.m., as Roosevelt sat in his comfortable study on the second floor of the White House, the long-apprehended phone call had come. Resting against the high back of his favorite red leather chair, a precise reproduction of one Thomas Jefferson had designed for work, the president listened as his ambassador to Belgium, John Cudahy, told him that Hitler’s armies were simultaneously attacking Holland, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France. The period of relative calm—the “phony war” that had settled over Europe since the German attack on Poland in September of 1939—was over.

For days, rumors of a planned Nazi invasion had spread through the capitals of Western Europe. Now, listening to Ambassador Cudahy’s frantic report that German planes were in the air over the Low Countries and France, Roosevelt knew that the all-out war he feared had finally begun. In a single night, the tacit agreement that, for eight months, had kept the belligerents from attacking each other’s territory had been shattered.

As he summoned his military aide and appointments secretary, General Edwin “Pa” Watson, on this spring evening of the last year of his second term, Franklin Roosevelt looked younger than his fifty-eight years. Though his hair was threaded with gray, the skin on his handsome face was clear, and the blue eyes, beneath his pince-nez glasses, were those of a man at the peak of his vitality. His chest was so broad, his neck so thick, that when seated he appeared larger than he was. Only when he was moved from his chair would the eye be drawn to the withered legs, paralyzed by polio almost two decades earlier.

At 12:40 a.m., the president’s press secretary, Stephen Early, arrived to monitor incoming messages. Bombs had begun to fall on Brussels, Amsterdam, and Rotterdam, killing hundreds of civilians and destroying thousands of homes. In dozens of old European neighborhoods, fires illuminated the night sky. Stunned Belgians stood in their nightclothes in the streets of Brussels, watching bursts of anti-aircraft fire as military cars and motorcycles dashed through the streets. A thirteen-year-old schoolboy, Guy de Lieder-kirche, was Brussels’ first child to die. His body would later be carried to his school for a memorial service with his classmates. On every radio station throughout Belgium, broadcasts summoned all soldiers to join their units at once.

In Amsterdam the roads leading out of the city were crowded with people and automobiles as residents fled in fear of the bombing. Bombs were also falling at Dunkirk, Calais, and Metz in France, and at Chilham, near Canterbury, in England. The initial reports were confusing—border clashes had begun, parachute troops were being dropped to seize Dutch and Belgian airports, the government of Luxembourg had already fled to France, and there was some reason to believe the Germans were also landing troops by sea.

After speaking again to Ambassador Cudahy and scanning the incoming news reports, Roosevelt called his secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., and ordered him to freeze all assets held by Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg before the market opened in the morning, to keep any resources of the invaded countries from falling into German hands.

The official German explanation for the sweeping invasion of the neutral lowlands was given by Germany’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Germany, he claimed, had received “proof” that the Allies were engineering an imminent attack through the Low Countries into the German Ruhr district. In a belligerent tone, von Ribbentrop said the time had come for settling the final account with the French and British leaders. Just before midnight, Adolf Hitler, having boarded a special train to the front, had issued the fateful order to his troops: “The decisive hour has come for the fight today decides the fate of the German nation for the next 1000 years.”

There was little that could be done that night—phone calls to Paris and Brussels could rarely be completed, and the Hague wire was barely working—but, as one State Department official said, “in times of crisis the key men should be at hand and the public should know it.” Finally, at 2:40 a.m., Roosevelt decided to go to bed. After shifting his body to his armless wheel chair, he rolled through a door near his desk into his bedroom.

As usual when the president’s day came to an end, he called for his valet, Irvin McDuffie, to lift him into his bed. McDuffie, a Southern Negro, born the same year as his boss, had been a barber by trade when Roosevelt met him in Warm Springs, Georgia, in 1927. Roosevelt quickly developed a liking for the talkative man and offered him the job of valet. Now he and his wife lived in a room on the third floor of the White House. In recent months, McDuffie’s hard drinking had become a problem: on several occasions Eleanor had found him so drunk that “he couldn’t help Franklin to bed.” Fearing that her husband might be abandoned at a bad time, Eleanor urged him to fire McDuffie, but the president was unable to bring himself to let his old friend go, even though he shared Eleanor’s fear.

McDuffie was at his post in the early hours of May 10 when the president called for help. He lifted the president from his wheelchair onto the narrow bed, reminiscent of the kind used in a boy’s boarding school, straightened his legs to their full length, and then undressed him and put on his pajamas. Beside the bed was a white-painted table; on its top, a jumble of pencils, notepaper, a glass of water, a package of cigarettes, a couple of phones, a bottle of nose drops. On the floor beside the table stood a small basket—the Eleanor basket—in which the first lady regularly left memoranda, communications, and reports for the president to read—a sort of private post office between husband and wife. In the corner sat an old-fashioned rocking chair, and next to it a heavy wardrobe filled with the president’s clothes. On the marble mantelpiece above the fireplace was an assortment of family photos and a collection of miniature pigs. “Like every room in any Roosevelt house,” historian Arthur Schlesinger has written, “the presidential bedroom was hopelessly Victorian—old-fashioned and indiscriminate in its furnishings, cluttered in its decor, ugly and comfortable.”

Outside Roosevelt’s door, which he refused to lock at night as previous presidents had done, Secret Service men patrolled the corridor, alerting the guardroom to the slightest hint of movement. The refusal to lock his door was related to the president’s dread of fire, which surpassed his fear of assassination or of anything else. The fear seems to have been rooted in his childhood, when, as a small boy, he had seen his young aunt, Laura, race down the stairs, screaming, her body and clothes aflame from an accident with an alcohol lamp. Her life was ended at nineteen. The fear grew when he became a paraplegic, to the point where, for hours at a time, he would practice dropping from his bed or chair to the floor and then crawling to the door so that he could escape from a fire on his own. “We assured him he would never be alone,” his eldest son, Jimmy, recalled, “but he could not be sure, and furthermore found the idea depressing that he could not be left alone, as if he were an infant.”

Roosevelt’s nightly rituals tell us something about his deepest feelings—the desire for freedom, the quest for movement, and the significance, despite all his attempts to downplay it, of the paralysis in his life. In 1940, Roosevelt had been president of the United States for seven years, but he had been paralyzed from the waist down for nearly three times that long. Before he was stricken at thirty-nine, Roosevelt was a man who flourished on activity. He had served in the New York legislature for two years, been assistant secretary of the navy for seven years, and his party’s candidate for vice-president in 1920. He loved to swim and to sail, to play tennis and golf; to run in the woods and ride horseback in the fields. To his daughter, Anna, he was always “very active physically,” “a wonderful playmate who took long walks with you, sailed with you, could out-jump you and do a lot of things,” while Jimmy saw him quite simply as “the handsomest, strongest, most glamorous, vigorous physical father in the world.”

All that vigor and athleticism ended in August 1921 at Campobello, his family’s summer home in New Brunswick, Canada, when he returned home from swimming in the pond with his children and felt too tired even to remove his wet bathing suit. The morning after his swim, his temperature was 102 degrees and he had trouble moving his left leg. By afternoon, the power to move his right leg was also gone, and soon he was paralyzed from the waist down. The paralysis had set in so swiftly that no one understood at first that it was polio. But once the diagnosis was made, the battle was joined. For years he fought to walk on his own power, practicing for hours at a time, drenched with sweat, as he tried unsuccessfully to move one leg in front of the other without the aid of a pair of crutches or a helping hand. That consuming and futile effort had to be abandoned once he became governor of New York in 1929 and then president in 1933. He was permanently crippled.

Yet the paralysis that crippled his body expanded his mind and his sensibilities. After what Eleanor called his “trial by fire,” he seemed less arrogant, less smug, less superficial, more focused, more complex, more interesting. He returned from his ordeal with greater powers of concentration and greater self-knowledge. “There had been a plowing up of his nature,” Labor Secretary Frances Perkins observed. “The man emerged completely warmhearted, with new humility of spirit and a firmer understanding of profound philosophical concepts.”

He had always taken great pleasure in people. But now they became what one historian has called “his vital links with life.” Far more intensely than before, he reached out to know them, to understand them, to pick up their emotions, to put himself into their shoes. No longer belonging to his old world in the same way, he came to empathize with the poor and underprivileged, with people to whom fate had dealt a difficult hand. Once, after a lecture in Akron, Ohio, Eleanor was asked how her husband’s illness had affected him. “Anyone who has gone through great suffering,” she said, “is bound to have a greater sympathy and understanding of the problems of mankind.”

Through his presidency, the mere act of standing up with his heavy metal leg-braces locked into place was an ordeal. The journalist Eliot Janeway remembers being behind Roosevelt once when he was in his chair in the Oval Office. “He was smiling as he talked. His face and hand muscles were totally relaxed. But then, when he had to stand up, his jaws went absolutely rigid. The effort of getting what was left of his body up was so great his face changed dramatically. It was as if he braced his body for a bullet.”

Little wonder, then, that, in falling asleep at night, Roosevelt took comfort in the thought of physical freedom.

• • •

The morning sun of Washington’s belated spring was streaming through the president’s windows on May 10, 1940. Despite the tumult of the night before, which had kept him up until nearly 3 a.m., he awoke at his usual hour of eight o’clock. Pivoting to the edge of the bed, he pressed the button for his valet, who helped him into the bathroom. Then, as he had done every morning for the past seven years, he threw his old blue cape over his pajamas and started his day with breakfast in bed—orange juice, eggs, coffee, and buttered toast—and the morning papers: The New York Times and the Herald Tribune, the Baltimore Sun, the Washington Post and the Washington Herald.

Headlines recounted the grim events he had heard at 11 p.m. the evening before. From Paris, Ambassador William Bullitt confirmed that the Germans had launched violent attacks on a half-dozen French military bases. Bombs had also fallen on the main railway connections between Paris and the border in an attempt to stop troop movements.

Before finishing the morning papers, the president held a meeting with Steve Early and “Pa” Watson, to review his crowded schedule. He instructed them to convene an emergency meeting at ten-thirty with the chiefs of the army and the navy, the secretaries of state and Treasury, and the attorney general. In addition, Roosevelt was scheduled to meet the press in the morning and the Cabinet in the afternoon, as he had done every Friday morning and afternoon for seven years. Later that night, he was supposed to deliver a keynote address at the Pan American Scientific Congress. After asking Early to delay the press conference an hour and to have the State Department draft a new speech, Roosevelt called his valet to help him dress.

• • •

While Franklin Roosevelt was being dressed in his bedroom, Eleanor was in New York, having spent the past few days in the apartment she kept in Greenwich Village, in a small house owned by her friends Esther Lape and Elizabeth Read. The Village apartment on East 11th Street, five blocks north of Washington Square, provided Eleanor with a welcome escape from the demands of the White House, a secret refuge whenever her crowded calendar brought her to New York. For decades, the Village, with its winding streets, modest brick houses, bookshops, tearooms, little theaters, and cheap rents, had been home to political, artistic, and literary rebels, giving it a colorful Old World character.

The object of Eleanor’s visit to the city—her second in ten days—was a meeting that day at the Choate School in Connecticut, where she was scheduled to speak with teachers and students. Along the way, she had sandwiched in a banquet for the National League of Women Voters, a meeting for the fund for Polish relief, a visit to her mother-in-law, Sara Delano Roosevelt, a radio broadcast, lunch with her friend the young student activist Joe Lash, and dinner with Democratic leader Edward Flynn and his wife.

The week before, at the Astor Hotel, Eleanor had been honored by The Nation magazine for her work in behalf of civil rights and poverty. More than a thousand people had filled the tables and the balcony of the cavernous ballroom to watch her receive a bronze plaque for “distinguished service in the cause of American social progress.” Among the many speakers that night, Stuart Chase lauded the first lady’s concentrated focus on the problems at home. “I suppose she worries about Europe like the rest of us,” he began, “but she does not allow this worry to divert her attention from the homefront. She goes around America, looking at America, thinking about America . . . helping day and night with the problems of America.” For, he concluded, “the New Deal is supposed to be fighting a war, too, a war against depression.”

“What is an institution?” author John Gunther had asked when his turn to speak came. “An institution,” he asserted, is “something that had fixity, permanence, and importance . . . something that people like to depend on, something benevolent as a rule, something we like.” And by that definition, he concluded, the woman being honored that night was as great an institution as her husband, who was already being talked about for an unprecedented third term. Echoing Gunther’s sentiments, NAACP head Walter White turned to Mrs. Roosevelt and said: “My dear, I don’t care if the President runs for the third or fourth term as long as he lets you run the bases, keep the score and win the game.”

For her part, Eleanor was slightly embarrassed by all the fuss. “It never seems quite real to me to sit at a table and have people whom I have always looked upon with respect . . . explain why they are granting me an honor,” she wrote in her column describing the evening. “Somehow I always feel they ought to be talking about someone else.” Yet, as she stood to speak that night at the Astor ballroom, rising nearly six feet, her wavy brown hair slightly touched by gray, her wide mouth marred by large buck teeth, her brilliant blue eyes offset by an unfortunate chin, she dominated the room as no one before her had done. “I will do my best to do what is right,” she began, forcing her high voice to a lower range, “not with a sense of my own adequacy but with the feeling that the country must go on, that we must keep democracy and must make it mean a reality to more people . . . . We should constantly be reminded of what we owe in return for what we have.”

It was this tireless commitment to democracy’s unfinished agenda that led Americans in a Gallup poll taken that spring to rate Mrs. Roosevelt even higher than her husband, with 67 percent of those interviewed well disposed toward her activities. “Mrs. Roosevelt’s incessant goings and comings,” the survey suggested, “have been accepted as a rather welcome part of the national ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter 1: “The Decisive Hour Has Come”

- Chapter 2: “A Few Nice Boys with BB Guns”

- Chapter 3: “Back to the Hudson”

- Chapter 4: “Living Here Is Very Oppressive”

- Chapter 5: “No Ordinary Time”

- Chapter 6: “I Am a Juggler”

- Chapter 7: “I Can’t Do Anything About Her”

- Chapter 8: “Arsenal of Democracy”

- Chapter 9: “Business As Usual”

- Chapter 10: “A Great Hour to Live”

- Chapter 11: “A Completely Changed World”

- Chapter 12: “Two Little Boys Playing Soldier”

- Chapter 13: “What Can We Do to Help?”

- Chapter 14: “By God, If It Ain’t Old Frank!”

- Chapter 15: “We Are Striking Back”

- Chapter 16: “The Greatest Man I Have Ever Known”

- Chapter 17: “It Is Blood on Your Hands”

- Chapter 18: “It Was a Sight I Will Never Forget”

- Chapter 19: “I Want to Sleep and Sleep”

- Chapter 20: “Suspended in Space”

- Chapter 21: “The Old Master Still Had It”

- Chapter 22: “So Darned Busy”

- Chapter 23: “It Is Good to Be Home”

- Chapter 24: “Everybody Is Crying”

- Chapter 25: “A New Country Is Being Born”

- Afterword

- Photographs

- ‘The Bully Pulpit’ Teaser

- A Note on Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright