- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hitchcock

About this book

Iconic, groundbreaking interviews of Alfred Hitchcock by film critic François Truffaut—providing insight into the cinematic method, the history of film, and one of the greatest directors of all time.

In Hitchcock, film critic François Truffaut presents fifty hours of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock about the whole of his vast directorial career, from his silent movies in Great Britain to his color films in Hollywood. The result is a portrait of one of the greatest directors the world has ever known, an all-round specialist who masterminded everything, from the screenplay and the photography to the editing and the soundtrack. Hitchcock discusses the inspiration behind his films and the art of creating fear and suspense, as well as giving strikingly honest assessments of his achievements and failures, his doubts and hopes. This peek into the brain of one of cinema’s greats is a must-read for all film aficionados.

In Hitchcock, film critic François Truffaut presents fifty hours of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock about the whole of his vast directorial career, from his silent movies in Great Britain to his color films in Hollywood. The result is a portrait of one of the greatest directors the world has ever known, an all-round specialist who masterminded everything, from the screenplay and the photography to the editing and the soundtrack. Hitchcock discusses the inspiration behind his films and the art of creating fear and suspense, as well as giving strikingly honest assessments of his achievements and failures, his doubts and hopes. This peek into the brain of one of cinema’s greats is a must-read for all film aficionados.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video

CHILDHOOD ■ BEHIND PRISON BARS ■ “CAME THE DAWN” ■ MICHAEL BALCON ■ “WOMAN TO WOMAN” ■ “NUMBER THIRTEEN” ■ INTRODUCING THE FUTURE MRS. HITCHCOCK ■ A MELODRAMATIC SHOOTING: “THE PLEASURE GARDEN” ■ “THE MOUNTAIN EAGLE”

1

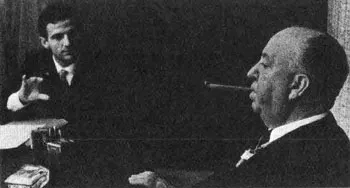

FRANÇOIS TRUFFAUT. Mr. Hitchcock, you were born in London on August 13, 1899. The only thing I know about your childhood is the incident at the police station. Is that a true story?

ALFRED HITCHCOCK. Yes, it is. I must have been about four or five years old. My father sent me to the police station with a note. The chief of police read it and locked me in a cell for five or ten minutes, saying, “This is what we do to naughty boys.”

F.T. Why were you being punished?

A.H. I haven’t the faintest idea. As a matter of fact, my father used to call me his “little lamb without a spot.” I truly cannot imagine what it was I did.

F.T. I’ve heard that your father was very strict.

A.H. Let’s just say he was a rather nervous man. What else can I tell you? Well, my family loved the theater. As I think back upon it, we must have been a rather eccentric little group. At any rate, I was what is known as a well-behaved child. At family gatherings I would sit quietly in a corner, saying nothing. I looked and observed a good deal. I’ve always been that way and still am. I was anything but expansive. I was a loner—can’t remember ever having had a playmate. I played by myself, inventing my own games.

I was put into school very young. At St. Ignatius College, a Jesuit school in London. Ours was a Catholic family and in England, you see, this in itself is an eccentricity. It was probably during this period with the Jesuits that a strong sense of fear developed—moral fear—the fear of being involved in anything evil. I always tried to avoid it. Why? Perhaps out of physical fear. I was terrified of physical punishment. In those days they used a cane made of very hard rubber. I believe the Jesuits still use it. It wasn’t done casually, you know; it was rather like the execution of a sentence. They would tell you to step in to see the father when classes were over. He would then solemnly inscribe your name in the register, together with the indication of the punishment to be inflicted, and you spent the whole day waiting for the sentence to be carried out.

F.T. I’ve read that you were rather average as a student and that your only strong point was geography.

A.H. I was usually among the four or five at the top of the class. Never first; second only once or twice, and generally fourth or fifth. They claimed I was rather absent-minded.

F.T. Wasn’t it your ambition, at the time, to become an engineer?

A.H. Well, little boys are always asked what they want to be when they grow up, and it must be said to my credit that I never wanted to be a policeman. When I said I’d like to become an engineer, my parents took me seriously and they sent me to a specialized school, the School of Engineering and Navigation, where I studied mechanics, electricity, acoustics, and navigation.

F.T. Then you had scientific leanings?

A.H. Perhaps. I did acquire some practical knowledge of engineering, the theory of the laws of force and motion, electricity—theoretical and applied. Then I had to make a living, so I went to work with the Henley Telegraph Company. At the same time I was taking courses at the University of London, studying art.

At Henley’s I specialized in electric cables. I became a technical estimator when I was about nineteen.

F.T. Were you interested in motion pictures at the time?

A.H. Yes, I had been for several years. I was very keen on pictures and the stage and very often went to first nights by myself. From the age of sixteen on I read film journals. Not fan or fun magazines, but always professional and trade papers. And since I was studying art at the University of London, Henley’s transferred me to the advertising department, where I was given a chance to draw.

F.T. What kind of drawings?

A.H. Designs for advertisements of electric cables. And this work was a first step toward cinema. It helped me to get into the field.

F.T. Can you remember specifically some of the films that appealed to you at the time?

A.H. Though I went to the theater very often, I preferred the movies and was more attracted to American films than to the British. I saw the pictures of Chaplin, Griffith, all the Paramount Famous Players pictures, Buster Keaton, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, as well as the German films of Decla-Bioscop, the company that preceded UFA. Murnau worked for them.

F.T. Can you single out a picture that made a special impression?

A.H. One of Decla-Bioscop’s most famous pictures was Der müde Tod.

F.T. Wasn’t that directed by Fritz Lang? The British title, I believe, was Destiny.

A.H. I guess so. The leading man, I recall, was Bernhard Goetzke.

F.T. Did you like Murnau’s films?

A.H. Yes, but they came later. In ’23 or ’24.

F.T. What films were being shown in 1920?

A.H. Well, I remember a Monsieur Prince. In England it was called Whiffles.

F.T. You’ve often been quoted as having said: “Like all directors, I was influenced by Griffith.”

A.H. I especially remember Intolerance and The Birth of a Nation.

F.T. How did you happen to go from Henley’s to a film company?

A.H. I read in a trade paper that an American company, Paramount’s Famous Players-Lasky, was opening a branch in Islington, London. They were going to build studios there, and they announced a production schedule. Among others, a picture taken from such and such a book. I don’t remember the title. While still working at Henley’s, I read that book through and then made several drawings that might eventually serve to illustrate the titles.

F.T. By “titles” you mean the captions that covered the dialogue in silent pictures?

A.H. That’s right. At the time, those titles were illustrated. On each card you had the narrative title, the dialogue, and a small drawing. The most famous of these narrative titles was “Came the dawn.” You also had “The next morning . . .” For instance, if the line read: “George was leading a very fast life by this time,” I would draw a candle, with a flame at each end, just below the sentence. Very naïve.

F.T. So you took this initiative and then submitted your work to Famous Players?

A.H. Exactly. I showed them my drawings and they put me on at once. Later on I became head of the title department. I went to work for the editorial department of the studio. The head of the department had two American writers under him, and when a picture was finished, the head of the editorial department would write the titles or would rewrite those of the original script. Because in those days it was possible to completely alter the meaning of a script through the use of narrative titles and spoken titles.

F.T. How so?

A.H. Well, since the actor pretended to speak and the dialogue appeared on the screen right afterward, they could put whatever words they liked in his mouth. Many a bad picture was saved in this way. For instance, if a drama had been poorly filmed and was ridiculous, they would insert comedy titles all the way through and the picture was a great hit. Because, you see, it became a satire. One could really do anything—take the end of a picture and put it at the beginning—anything at all!

F.T. And this gave you a chance to see the inside of film-making?

A.H. Yes. At this time I met several American writers and I learned how to write scripts. And sometimes when an extra scene was needed—but not an acting scene—they would let me shoot it. However, the pictures made by Famous Players in England were unsuccessful in America. So the studio became a rental studio for British producers.

Meanwhile, I had read a novel in a magazine, and just as an exercise, I wrote a script based on this story. I knew that an American company had the exclusive world rights to the property, but I did it anyway, since it was merely for practice.

When the British companies took over the Islington studios, I approached them for work and I landed a job as an assistant director.

F.T. With Michael Balcon?

A.H. No, not yet. Before that I worked on a picture called Always Tell Your Wife, which featured Seymour Hicks, a very well-known London actor. One day he quarreled with the director and said to me, “Let’s you and me finish this thing by ourselves.” So I helped him and we completed the picture.

Meanwhile, the company formed by Michael Balcon became a tenant at the studios, and I became an assistant director for this new venture. It was the company that Balcon had set up with Victor Saville and John Freedman. They bought the rights to a play. It was called Woman to Woman. Then they said, “Now we need a script,” and I said, “I would like to write it.” “You? What have you done?”

I said, “I can show you something.” And I showed them the adaptation I’d written as an exercise. They were very impressed and I got the job. That was in 1922.

Betty Compson and Clive Brook in Woman to Woman.

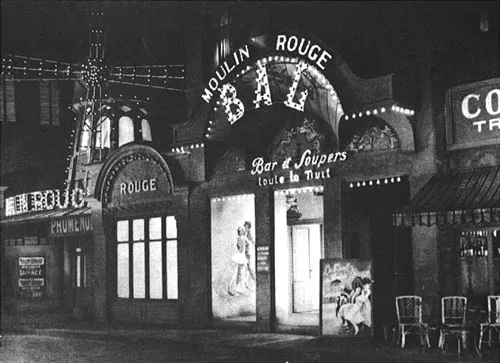

Set created by Hitchcock for Woman to Woman.

Number Thirteen, (1922).

F.T. I see. You were then twenty-three. But didn’t you direct a little picture called Number Thirteen before that time?

A.H. A two-reeler. It was never completed.

F.T. Wasn’t it a documentary?

A.H. No. There was a woman working at the studio who had worked with Chaplin. In those days anyone who had worked with Chaplin was top drawer: She had written...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Acknowledgment

- Preface to the Revised Edition

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- The Films of Alfred Hitchcock

- Selected Bibliography

- Index of Film Titles

- Index of Names

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hitchcock by Francois Truffaut in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.