![]()

1

TOGETHER AND APART

Encapsulation and the Automobile

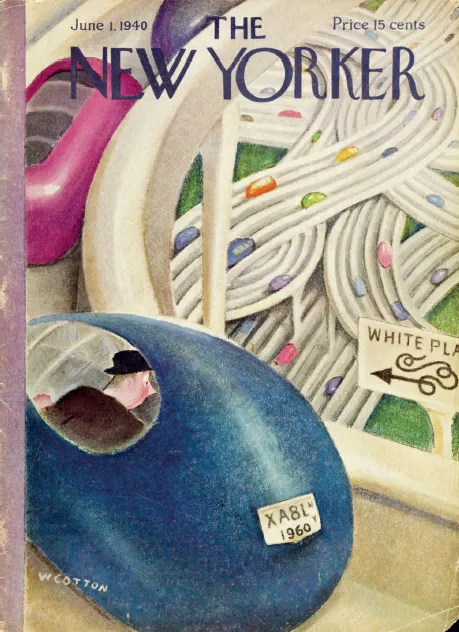

Our car has taken us back to 1960. More precisely, we are in what 1940 imagined 1960 would be like: clueless drivers riding in capsules along monumental spaghetti junctions. The New Yorker cover satirizes the wildly popular General Motors Futurama pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair (fig. 2). The exhibition, mounted by designer Norman Bel Geddes, was meant as a preview of the American city in twenty years—a place where the car reigned supreme (unsurprisingly, given the sponsor). Thanks to a carry-go-round conveyor, visitors flew above dioramas of superhighways, greenbelts, and streamlined glass towers, and were eventually ejected into a life-size intersection.1

When he traveled to California in the mid-1950s, South African writer Dan Jacobson was also catapulted to the heart of Bel Geddes’s vision—only Futurama was now present tense. To his unaccustomed eyes, the massive highways jam-packed with high-speed traffic resembled a glimpse into the world of tomorrow. How could such a diverse country exist as one and yet be divided up into countless bubbles on wheels? E pluribus unum? Jacobson also witnessed the suburban boom that relied on such a technology, its pattern evoking a parallel feeling of disjuncture and indifference. “It is the flat dispersion, equality, and separation of the suburb,” he wrote, “that most approximates to my idea of the shape of American society.”2 Cars were the glaring symbol of this fractured vision. Their number had doubled from 25 million in 1945 to 52 million in 1955; in terms of registration per year, the figure quintupled from 1946 to 1965.3 Already in 1960, four out of five households owned at least one car, and by 1970 the nation boasted over 108 million personal vehicles, leaving only 17 percent of U.S. families without one in the driveway.4 Not even the fuel crisis managed to stop this rise. The total number of car owners rose to over 87 percent of the population in 1980, and half of American families owned more than one.5

Figure 2. William Cotton. Untitled cover illustration. New Yorker, 1 June 1940. (© Condé Nast)

The car became so widespread that it is hard to imagine America could ever have existed without it. One feels tempted to look for a reference to the Cadillac between “the course of human events” and “the pursuit of happiness.” Many commentators have explained the country’s headlong conversion to private transportation by suggesting that Uncle Sam and Tin Lizzie were made for each other from the start. It was a “a love affair,” social critic John Keats wrote in 1958.6 From then on, scholars were apt to evoke similar scenarios, either inflated into a marriage or downplayed as infatuation; but it was romance nonetheless, perhaps even “religion,” as Lewis Mumford proposed.7 All such arguments implied an irrational attraction, but in doing so they disregarded the social processes leading to the adoption of the car. They mistook America’s cultural specificities for sentiment or genetic predisposition.

Marxist readings of the automobile as “the Leading-Object” or “the ur commodity” are not particularly useful in identifying what informed consumer behavior.8 The insistence on objectness fails to address its transformative power over the landscape. In fact, the car acts on space as a space itself; it caters to desires that lie well beyond simply being moved about. To be inside a car is to experience a completely changed perception of the outer environment. The automobile is like portable real estate: the condition of the carless subject in America is closer to homelessness than mere deprivation of an essential good. Not owning a car implies exposure and lack of opportunity.

As a space, the car was the first in a long line of interiors devised as escape pods. One still sees this mindset at work in ads picturing automobiles in rugged settings, hurtling up mountain roads, down sprawling meadows, and across deserts. At first, it might look as if the car allowed its driver a way out of civilization rather than a tie to its web of commitments. However, the imagery only displaces the escapist dream that is inscribed in its interior, one of whose functions is to remove drivers from the human proximity of public transit.9 Just as Leonardo measured the whole world against the proportion of his Vitruvian man, the mid-century motor Renaissance placed the encapsulated driver at its center. Within this autocentric vision, mass availability of the automobile was understood as a democratic arrangement extending beyond gender, race, or social background, and the democratization of the car ultimately sanctioned the democratization of suburbia.10 However, this assumption once again dehistoricizes the car. It overlooks that it is the autocentric design of space that makes the car a necessary precondition for freedom in a car-dominated society. The automobile thus becomes an instrument of democracy only if dependency on private transportation is assumed as inevitable.

If one bothers to flip the record, the B-side of this smash hit reveals the impressive decline of the city and public transportation, both struggling to accommodate all those who were written out of the car’s success story.11 In fact, the car was conceptualized as an interior because of the power of exclusion and escape that spatial segregation could grant. Only by looking at how the understanding of the automobile evolved over the years can one unravel the rise of the postwar suburban interior and its initial detachment from the exterior.

The Evolution of the Closed Car

Looking for the cause that first triggered the spread of the automobile, historians have often pointed to Ford’s Model T, one of the first cases of industrial mass consumption, with fifteen million sold between 1908 and 1927. But if one considers the revolution of the car to be its provision of a moving personal space, the event that broke new ground was the introduction of the closed body in the 1920s. The closed car was the first private vehicle that, unlike the horse-and-buggy, enclosed both passengers and pilot in the same protected cabin.

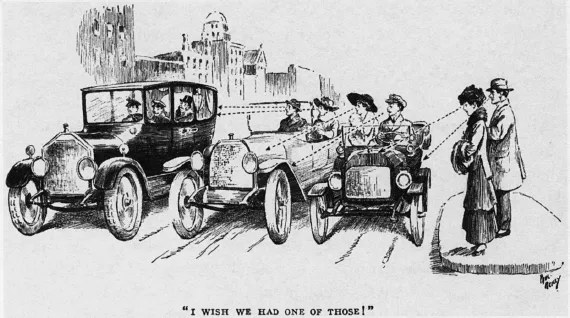

Figure 3. Paul Reilly. “I Wish We Had One of Those!” Life, 1916.

Before the early 1920s, the most common models were open vehicles such as the touring car and the roadster, which were suitably adapted to a landscape not yet redesigned for efficient motorized travel, at a time when poor road conditions threatened to damage glass or metal parts.12 The Model T itself was a roofless carriage with a few convertible components. Only the well-to-do could afford the luxury of a closed car. A 1916 Life cartoon depicted pedestrians hankering after a touring car while its riders dreamed of a closed sedan, which at the time accounted for only 2 percent of the automobile market (fig. 3). By 1919, that figure had only risen to 10 percent.13

In the days of the open car, driving was seen as a sociable pastime, a chance for urbanites and yeomen to bond, thanks to the vehicle’s penetrability. “Automobiling is democratic,” sociologist Charles Horton Cooley commented in 1923, “because it brings all sorts of people face to face, and mostly under fellowship conditions … to give and receive courtesy and help.”14 Ralph Epstein, one of the first historians of the automobile, wrote that the car furthered “the readier observation and comparison of different places and practices; it greatly encourages social interaction.”15

The Laurel and Hardy film Two Tars depicted the downsides of open-car sociability in its portrayal of a country road gridlock in which two sailors and their dates get stuck with their tourer.16 Road rage ensues with the first unintentional collisions. It isn’t long before drivers start mangling the cars’ chassis and deliberately bumping into one another. In fact, the fight escalates because drivers are not yet shielded by an interior that contains their temper. The pantomime ends with a train sweeping away all the vehicles as they mistakenly drive into a rail tunnel. The car was still grappling with the landscape to carve out a space of its own.

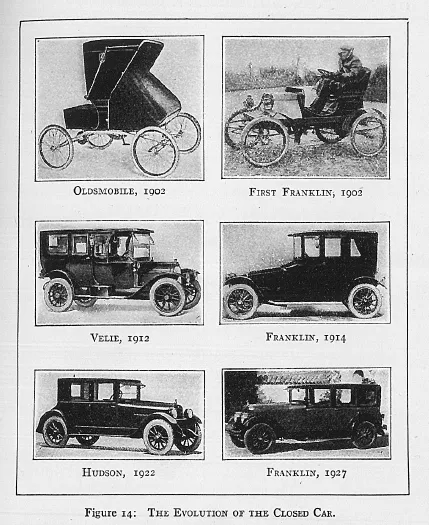

All this changed in 1922, when Hudson marketed the closed Essex at a price that was still far from the average pocket but not that distant from that of their touring car. Other manufacturers followed suit. By 1927, four out of five drivers traveled in a closed car.17 Gone were the days of convivial or belligerent get-togethers in the country, of drivers meeting face to face. In this sealed space, driving was evolving into a more privatized activity. Illustrations of the time presented the switch to the closed body in evolutionary terms, implying automotive technology had organically grown away from the primitive and vulnerable to the solid and sheltering. In these visual narratives, the interior stood out as the space of luxury and progress (fig. 4).

The closed body led to a major improvement in traveling conditions. One of the many benefits was that drivers were now sheltered from bad weather, as advertisers frequently reminded them (figs. 5–6). Driving grew into a utilitarian activity no longer carried out in dicey circumstances. The evolution also shifted the perception of the machine from a collection of body elements to a consistent unit enclosed by an outer shell: a space to inhabit, with sofa-like seats and cozy upholstery.18 Drawing on gendered binaries, most ads addressed the female audience for whom the homelike environment seemed better suited. Male consumers showed some resistance, attached as they were to the ideal of the open tourer as the proper “man’s car,” as a California motorist put it.19 But the spread of the intimacy bestowed on the hearth since Victorian times out of the confines of the house led to the first clashes with the public realm. Sexual encounters in the closed car rose together with the profits of carmakers, leading the Pasadena police chief to chastise the novelty as “the greatest menace now facing the morals of Pasadena youth.” “The coupe and sedan,” he proclaimed, “have replaced the old-time red-light district.”20

Figure 4. The Evolution of the Closed Car. From Ralph C. Epstein, The Automobile Industry: Its Economic and Commercial Development, 1928.

The feminization of the car’s interior also conveyed the impression that the closed body delivered protection to those who needed it most. “Why worry about the safety of your little ones on the highways or crossing city streets on the way to school?,” a 1923 ad asked concerned “mothers or big sisters”; “the low price and small upkeep of a Chevrolet is cheap insurance against such risks.”21 “Self preservation is the first law of Nature,” Budd All-Steel reminded prospective buyers; “Today, with 19,000,000 cars crowding the highways … America is turning to the All-Steel Body.”22 The Ford Company described the car ...