- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

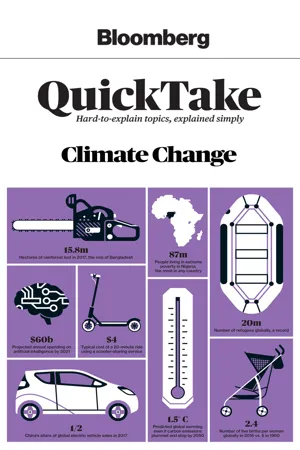

Bloomberg QuickTake: Climate Change

About this book

Hot subjects in business, politics (and much more) untangled with easy-to-understand prose and smart graphics, from the world's leading financial media company. This volume of Bloomberg QuickTake has a special section that focuses on how climate change is influencing where we live, how we invest, and even what clothes we buy. Other sections include Finance & Capital Markets; Trade; Global Governance; Urbanization; Inclusion; and Technology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Buzzwords

Environmental challenges come with their own catchwords. Here’s assistance decoding them.

By Alessandro Giovanni Borghese

Take, make, use, dispose. For centuries, this has been the standard approach to production and consumption. This model is increasingly being challenged by people who say it’s inefficient and costly and can harm the environment and deplete natural resources. The European Union and the governments of China, Japan and the U.K. are among those advocating that we ditch this linear system in favor of a model of take, make, use, reuse and reuse again and again. The term “circular economy” has been in circulation among economists for decades. It has recently come to connote an approach to the reuse of produced goods and materials that’s more ambitious than recycling. Companies around the world are starting to embrace the concept. For example, Singapore-based tire maker Omni United designed a model that can be repurposed to make soles for Timberland shoes. Some analysts are skeptical about the feasibility of the model on a large scale, citing high startup expenses as a primary concern. A 2015 study estimated that the cost of shifting to a circular economy for five European countries would be 3 percent of gross domestic product per year until 2030.

By Eric Roston

How much climate change hurts future generations depends on what’s done to limit the change and what’s done to protect against its impact. Those two categories are known as mitigation and adaptation, and there’s a robust argument among governments, businesses and environmentalists over how to balance the effort put into each. Mitigation — limiting the change — gets most of the attention, but adaptation — cushioning its impact — is moving from a theoretical strategy to a practical need as temperatures rise. Some communities are already trying to relocate away from rising waters. Storm-surge barriers and floodgates geared to climate change have gone up in Rotterdam and Venice. New York installed gates after parts of the city were inundated by the surge driven by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and Houston, flooded by Hurricane Harvey’s torrential rains in 2017, is considering new defenses. While those are huge projects, even steps as small as providing air conditioners for the poor can help make hotter cities more livable. A subset of adaptation is resilience, the ability to adjust to and recover from whatever nature throws at us. Focusing on resilience may also be a way to avoid controversy in countries where global warming is a partisan issue.

By Allegra Catelli and Ellen Milligan

To keep you looking good, the fashion industry consumes a lot of resources and creates a lot of mess. An estimated 17 percent of industrial water pollution comes from the dyeing and treating of textiles. The water required to grow the cotton in a single T-shirt could sustain a person for three years. With clothing output roughly doubling in the past 15 years, carbon emissions from textile production exceed those of maritime shipping and international flights combined. But apparel makers are starting to commit to more efficient water use, better recycling systems and the development of more sustainable fibers. Some companies that have made such pledges, including Hennes & Mauritz AB and Burberry Group Plc, have faced criticism for burning unsold clothes worth millions of dollars. Burning avoids the cost of recycling or discounting such stock, and keeps merchandise rare, protecting its premium. There’s a long way to go before green is the new black.

Climate Change

By Eric Roston

Is there still a debate over climate change? Yes and no. As a scientific matter, the issues of whether it’s happening and who’s to blame are long settled. But there’s no end to debates about what to do about it. Arguments about the need for and costs of action are playing out against a nonstop, live-on-TV drama of the massive storms, record wildfires and deadly heat waves already fueled by global warming.

What’s new in the climate debate?

There’s been a revolution in renewable energy. The price of wind and solar has plunged in a way their most ardent backers wouldn’t have dared dream 20 years ago. Bloomberg NEF projects that by 2050, renewables will produce two-thirds of global electricity, the same share that fossil fuels produce today. The world’s biggest polluter, China, is ahead of schedule for its emissions to peak by 2030, thanks to a combination of slower economic growth and a drive for cleaner air.

There’s been a revolution in renewable energy. The price of wind and solar has plunged in a way their most ardent backers wouldn’t have dared dream 20 years ago. Bloomberg NEF projects that by 2050, renewables will produce two-thirds of global electricity, the same share that fossil fuels produce today. The world’s biggest polluter, China, is ahead of schedule for its emissions to peak by 2030, thanks to a combination of slower economic growth and a drive for cleaner air.

GRAPHIC SOURCES: UN, WORLD BANK

Where does the Paris accord stand?

Even though President Donald Trump intends to pull the world’s biggest economy out of the 2015 pact, which is meant to limit global warming, the U.S. is still participating in discussions on implementing the pledges made by almost 200 countries. Coalitions of cities, states, businesses and universities in groups such as We Are Still In and America’s Pledge have organized to keep progress going in the U.S. even if the country leaves the pact. (America’s Pledge was co-founded by Michael Bloomberg, the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News.) The U.S. is seen as on track for its climate goals for 2020 but falling short of its longer-term pledges, as are the European Union and Japan, according to Climate Action Tracker, a research project.

Even though President Donald Trump intends to pull the world’s biggest economy out of the 2015 pact, which is meant to limit global warming, the U.S. is still participating in discussions on implementing the pledges made by almost 200 countries. Coalitions of cities, states, businesses and universities in groups such as We Are Still In and America’s Pledge have organized to keep progress going in the U.S. even if the country leaves the pact. (America’s Pledge was co-founded by Michael Bloomberg, the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News.) The U.S. is seen as on track for its climate goals for 2020 but falling short of its longer-term pledges, as are the European Union and Japan, according to Climate Action Tracker, a research project.

What’s Trump’s argument?

Money. Trump said the Paris pact would hurt American workers and amounted to a “massive redistribution” of wealth to other countries. Meeting the Paris goals would conflict with his efforts to revive U.S. coal production. He’s also moved to water down fuel-efficiency standards and proposed rolling back regulations meant to force utilities to reduce emissions. Trump aides insist that U.S. economic growth is a more urgent priority than climate change.

Money. Trump said the Paris pact would hurt American workers and amounted to a “massive redistribution” of wealth to other countries. Meeting the Paris goals would conflict with his efforts to revive U.S. coal production. He’s also moved to water down fuel-efficiency standards and proposed rolling back regulations meant to force utilities to reduce emissions. Trump aides insist that U.S. economic growth is a more urgent priority than climate change.

Who’s agreeing with him?

Influential groups of voters in countries where a shift away from dirty fuels has raised energy prices. In Australia, Malcolm Turnbull was pushed out as prime minister in August after conservatives in his party rebelled over his plan to write the country’s Paris targets into law. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2015 bowed to pressure to allow pipelines carrying carbon-heavy oil from tar sands to be expanded. Now his plan for a national carbon price to drive down emissions is under attack and is expected to be a focus for his opponents in 2019 elections.

Influential groups of voters in countries where a shift away from dirty fuels has raised energy prices. In Australia, Malcolm Turnbull was pushed out as prime minister in August after conservatives in his party rebelled over his plan to write the country’s Paris targets into law. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2015 bowed to pressure to allow pipelines carrying carbon-heavy oil from tar sands to be expanded. Now his plan for a national carbon price to drive down emissions is under attack and is expected to be a focus for his opponents in 2019 elections.

How much would real action cost?

It’s hard to know, and there’s a wide range of forecasts. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that meeting Paris targets would require $2.4 trillion in annual investments in low-carbon energy sources through 2035. That’s almost seven times more than BNEF says was invested in 2017. Developed nations promised to boost climate-related aid to poorer countries to $100 billion a year by 2020. But only $3.5 billion has been committed so far.

It’s hard to know, and there’s a wide range of forecasts. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that meeting Paris targets would require $2.4 trillion in annual investments in low-carbon energy sources through 2035. That’s almost seven times more than BNEF says was invested in 2017. Developed nations promised to boost climate-related aid to poorer countries to $100 billion a year by 2020. But only $3.5 billion has been committed so far.

What are the stakes?

The IPCC’s scientists calculate that even if the Paris pledges are met, we’d miss the accord’s target of holding warming to 2C (3.6F) above 1850 levels. If current emissions levels aren’t reduced, warming could gallop past 3C, with potentially catastrophic effect: Studies have projected changes ranging from more kidney stones, smaller goats and less sex in the shorter run to swamped cities and widespread extinctions of species in the decades ahead. The UN panel calls for vast changes, fast. By its figures, holding warming to 1.5C, a more aggressive goal targeted in Paris, would require cutting emissions by roughly half from 2010 levels by 2030. And even that would mean we’re in for as much warming as we’ve already lived through since 1990.

The IPCC’s scientists calculate that even if the Paris pledges are met, we’d miss the accord’s target of holding warming to 2C (3.6F) above 1850 levels. If current emissions levels aren’t reduced, warming could gallop past 3C, with potentially catastrophic effect: Studies have projected changes ranging from more kidney stones, smaller goats and less sex in the shorter run to swamped cities and widespread extinctions of species in the decades ahead. The UN panel calls for vast changes, fast. By its figures, holding warming to 1.5C, a more aggressive goal targeted in Paris, would require cutting emissions by roughly half from 2010 levels by 2030. And even that would mean we’re in for as much warming as we’ve already lived through since 1990.

Carbon Pricing

By Mathew Carr

It’s an idea that’s been around for more than two decades: To slow climate change, make polluters pay for the damage they cause. More than 60 nations, states and cities have adopted what’s known as carbon pricing, an approach held up by environmentalists, global institutions and even many oil companies as an elegant, free-market approach to global warming — one that creates incentives to find the best solutions and avoids burdensome regulation. In practice, though, carbon pricing has proved politically difficult, reflecting pushback from the public as well as business groups.

How does carbon pricing work?

Governments either levy a tax on each metric ton of carbon dioxide emitted or start a market to trade permits to pollute. In both cases, companies in certain industries are targeted — say, utilities that produce electricity — which means that carbon pricing will only cover a portion of a country’s total emissions. With a market, a limit is set on the total volume of emissions allowed, then permits are either allocated or purchased by polluters. The credits can then be bought and sold, a system known as cap-and-trade.

Governments either levy a tax on each metric ton of carbon dioxide emitted or start a market to trade permits to pollute. In both cases, companies in certain industries are targeted — say, utilities that produce electricity — which means that carbon pricing will only cover a portion of a country’s total emissions. With a market, a limit is set on the total volume of emissions allowed, then permits are either allocated or purchased by polluters. The credits can then be bought and sold, a system known as cap-and-trade.

GRAPHIC: PRICES ON APRIL 1, 2018. TAX AND ETS REVENUE ESTIMATES BASED ON GOVERNMENT BUDGETS AND ANNUAL PERMITS DISTRIBUTED. TAX IN MEXICO AND NORWAY VARIES WITH FUEL TYPE, IN DENMARK WITH TYPE OF GAS EMITTED; SOURCES: WORLD BANK, ECOFYS

Is carbon pricing effective?

Environmentalists say most policy makers have been unwilling to set prices high enough to force changes in behavior, or to make enough companies pay them. That said, the levies have encouraged more switching to cleaner natural gas, and their cost has begun to creep into electricity prices around the world. The U.K.’s carbon tax is credited with helping the country rapidly phase out coal.

Environmentalists say most policy makers have been unwilling to set prices high enough to force changes in behavior, or to make enough companies pay them. That said, the levies have encouraged more switching to cleaner natural gas, and their cost has begun to creep into electricity prices around the world. The U.K.’s carbon tax is credited with helping the country rapidly phase out coal.

How widespread is it?

About 40 countries and jurisdictions have developed or plan to start carbon markets, including China, the European Union and a handful of U.S. states. About half that number have a carbon tax, from roughly $1 a ton in Mexico to $139 in Sweden. Many countries — such as the U.K. and most Scandinavian nations — use permit trading alongside targeted taxes on dirty fuels such as coal. Still, carbon pricing only covers about 20 percent of global emissions. California’s program is one of the few that includes transport fuels.

About 40 countries and jurisdictions have developed or plan to start carbon markets, including China, the European Union and a handful of U.S. states. About half that number have a carbon tax, from roughly $1 a ton in Mexico to $139 in Sweden. Many countries — such as the U.K. and most Scandinavian nations — use permit trading alongside targeted taxes on dirty fuels such as coal. Still, carbon pricing only covers about 20 percent of global emissions. California’s program is one of the few that includes transport fuels.

How high does the price need to be?

A price of about $40 a ton, among other climate policies, is needed to achieve targets in the 2015 United Nations Paris accord to stem climate change, according to a 2017 report from a commission of economists and scientists. The price would need to rise to more than $100 a ton by the middle of the century to keep up with the Paris pledges and encourage expensive technologies such as carbon capture and storage. About half of the almost 200 nations that signed the agreement expect to use some form of carbon pricing to reach their goals.

A price of about $40 a ton, among other climate policies, is needed to achieve targets in the 2015 United Nations Paris accord to stem climate change, according to a 2017 report from a commission of economists and scientists. The price would need to rise to more than $100 a ton by the middle of the century to keep up with the Paris pledges and encourage expensive technologies such as carbon capture and storage. About half of the almost 200 nations that signed the agreement expect to use some form of carbon pricing to reach their goals.

Who’s opposed to carbon pricing?

Political leaders h...

Political leaders h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Editor's Letter

- Calendar Guide to 2019

- FINANCE & CAPITAL MARKETS

- TRADE

- GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

- CLIMATE

- URBANIZATION

- INCLUSION

- TECHNOLOGY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bloomberg QuickTake: Climate Change by Bloomberg News in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.