This is a test

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

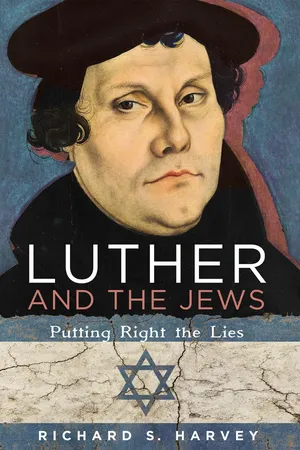

Luther and the Jews: Putting Right the Lies is a timely and important contribution to the debate about the legacy of the Protestant Reformation. It brings together two topics that sit uncomfortably: the life, ministry, and impact of Martin Luther, and the history of Jewish-Christian relations to which he made a profoundly negative contribution. As a Messianic Jew, Richard Harvey considers Luther and his legacy today, and explains how Messianic Jews have a vital role to play in the much-needed reconciliation not only between Protestants and Catholics, but also between Christians and Jews, in order for Luther's vision of the renewal and restoration of the church to be realized.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Luther and the Jews by Harvey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

History of Christianitychapter 1

Who was Martin Luther?

Early Life

Late in the evening of 10 November 1483 the first of nine children was born to Hans and Margarethe Luder3 of Eisleben in the county of Mansfeld, in the central region of Germany. The following day he was baptized in the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, and given the name of the saint of that day, Martin (of Tours).

Hans and Margarethe were hard-working farming people, but Hans did not inherit the family farm in Möhra, and moved eighty miles away from friends and family to Eisleben, where he become a miner in the hope of earning a better living in the local copper mine. Hard work and tight control of the family finances made him a successful and well-to-do merchant. Margarethe also worked hard to bring up the large family, and Martin grew up knowing his parents also had high expectations of him. A university education, a successful career in law, and the responsibilities of marriage and family life (like his parents) were the expectations placed on him from an early age. His habits of working hard and respecting family life remained with him, as a result of his strict, disciplined but loving upbringing.

Map of Luther’s Germany—key towns and regions

His schooling in Mansfeld and nearby Eisenach, from ages seven to sixteen, prepared him for university studies at Erfurt, where he lived in a hostel run under the strict principles of a monastery. This included communal prayer four times a day, chores, breakfast, private studies, etc. Martin was an able student, and graduated with excellence in the combination of studies of the Middle Ages, grammar, logic, and rhetoric (trivium), which prepared students for careers in law, medicine, or theology in four years, the shortest possible time.

By 1501 he had moved schools three times, and in later life felt that his teachers had been unduly harsh towards him, but in 1502 he was able to pass his baccalaureate exams in the several liberal arts of grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Three years of further study in philosophy, logic, mathematics, and music followed. In 1505, at the age of twenty-two, he graduated second in his class of seventeen, and was ready to study the profession marked out for him by his father as the most promising for his future: law.

But despite his parents’ wishes and expectations, his life would take a very different course. In 1504, just before his twenty-first birthday, he had suffered an accident with a friend’s sword and sustained a serious injury. The possibility of death and coming before God’s judgment terrified him. He later called this experience his anfechtung (trial, temptation, tribulation, or affliction), so severely was he moved by it. He felt he would die and be cast into hell as punishment for his sins. This paralyzing fear of death, judgment, and hell would traumatize him throughout his life, but particularly plagued the young Martin. An outbreak of the plague in 1505 caused the deaths of some of his fellow students, and he had moments where he could do nothing, so terrified was he of what might happen.

Then on the night of 2 July 1505, he was caught in a sudden thunderstorm on his way back to Erfurt from a visit to his parents in Mansfeld, on the road near Stottenheim. A bolt of lightning struck right beside him. His legs could feel the electric current vibrate around him. Terrified he was about to die, he vowed “Save me, St. Anna, and I will become a monk.” Profoundly shaken by this Stottenheim road experience, fifteen days later he joined the Augustinian hermits of Erfurt, committing himself to a life of prayer, service and study.

So angry was his father at hearing this news, that a conflict between them began that would continue for another twenty years, when Luther was eventually, and as an outcome of his revolutionary teaching about the monastic life, to take a wife. But these thoughts were far from Luther’s mind now. He devoted himself to a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience, seeking the inner peace he so longed for. However, the life of intense religious practices only made things worse. He was aware of his sinfulness. The regular practice of confessing his sins only made him feel more guilty and less forgiven. His awe of God was not met with a sense of God’s love and acceptance, and once ordained as a priest and taking his first Mass, he was speechless because of his fear at being in the presence of God, and tried to run away from the service. Only a telling-off from his teacher made him continue.

Luther’s understanding of God as the Almighty filled him with fear. He was anxious and miserable as he thought of having to stand before the Judge of the world and give an account of his life. So he pushed himself to study the Bible more thoroughly. Up to this time, study of the Scriptures had been primarily to justify the teaching of the church, and to illustrate the philosophical arguments of the Scholastics, men like Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus, who had tried to bring the teachings of the church in line with the teachings of the Greek philosophers, Plato and Aristotle. But Luther came to the Word of God looking for answers to his own personal dilemmas.

He studied the Bible in depth, learning the original languages of Greek and Hebrew, and gaining a reputation for his outstanding knowledge. Eventually, his monumental achievement of translating the Bible into the language of the common people would demonstrate his mastery of the library of books that make up the Old and New Testaments. It would become the foundation for all he would later write and teach, and his basis for argument as he challenged the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. He later wrote “The Scriptures are a vast forest, but there is not one tree in it that I have not shaken with my hand.”4

With the invention of printing, copies of the Bible were now more available, and the young monk may have obtained his own copy. His studies in theology in Erfurt, then Wittenberg in 1508, and some time in Rome, led to him joining the theology faculty at Wittenberg and graduating as a Doctor (teacher) of Theology in 1513. He began teaching the Bible in the same year, concentrating on lectures on Genesis and Psalms. His lectures were well-prepared, and although he was not the greatest Hebrew scholar, he made copious notes on the grammar and questions of translation, and gave his students detailed notes on the theology of each section. In 1515 he moved on to Romans, and was drawn to the thought of the apostle Paul, especially his understanding of law, grace, and salvation.

Luther realized that the key problem he faced—how he could appear before the judgment of an angry God—was answered by the doctrine of justification by faith alone, and not his own works of righteousness or attempts to justify himself. The text “the just shall live by faith” transformed his life and removed his deep-seated sense of guilt, fear, and judgment. He wrote:

I greatly longed to understand Paul’s Epistle to the Romans and nothing stood in the way but that one expression, “the justice of God,” because I took it to mean that justice whereby God is just and deals justly in punishing the unjust. My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Therefore I did not love a just and angry God, but rather hated and murmured against him. Yet I clung to the dear Paul and had a great yearning to know what he meant.

Night and day I pondered until I saw the connection between the justice of God and the statement that “the just shall live by his faith.” Then I grasped that the justice of God is that righteousness by which through grace and sheer mercy God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. The whole of Scripture took on a new meaning, and whereas before the “justice of God” had filled me with hate, now it became to me inexpressibly sweet in greater love. This passage of Paul became to me a gate to heaven. . . .

If you have a true faith that Christ is your Savior, then at once you have a gracious God, for faith leads you in and opens up God’s heart and will, that you should see pure grace and overflowing love. This it is to behold God in faith that you should look upon his fatherly, friendly heart, in which there is no anger nor ungraciousness. He who sees God as angry does not see him rightly but looks only on a curtain, as if a dark cloud had been drawn across his face.5

Teaching and Preaching

Luther’s responsibilities now included preaching regularly at the church in Wittenberg, close to the castle that housed the Augustinian monastery where he lived. He became the district vicar for ten monasteries, which brought much administrative responsibility and was time consuming, but gave him detailed understanding of caring for both personal, spiritual, and pastoral needs. Many confessed to problems of sin and guilt that alienated them from God and one another. The answer for them was the sacrament of penance, which involved showing repentance (contrition), confessing their sin to a priest, and seeking absolution. On confession of their sin the priest would prescribe a series of acts of contrition to satisfy the requirements of God’s justice and judgment, but often these acts were not completed, and the sinner was left lacking “satisfaction.” If they d...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Can Anything Good Come Out of Wittenberg?

- Chapter 1: Who was Martin Luther?

- Chapter 2: Who Are the Jewish people?

- Chapter 3: Luther’s Lies about the Jews

- Chapter 4: What Did Luther Say about the Jews?

- Chapter 5: Reconciliation

- Chapter 6: What if . . . ?

- Chapter 7: Conclusion

- Further Reading and Resources

- Appendix: Lament over the Wittenberg Judensau

- Bibliography