![]()

Chapter 1

FEMINISM AND CONCEPTUAL PRACTICE

The day before I went to Paris this guy came in and asked me to tell him about the show, saying he was a journalist for the Evening Standard. I told him about it but said that there was no need [to review it] because Richard Cork was going to review it. What he’d done was to see Cork’s copy in his tray on his desk, saw the word “nappies”, and got straight around to the ICA. And that’s how the shit hit the fan … and I think it was the first time that questions were asked in the House of Commons about art.1

INTRODUCTION

Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document occupies one of the defining moments of feminist art in London during the 1970s. She is the first artist mentioned in discussions on the women’s movement and the visual arts in this city during that decade.2 Part of the reason for her centrality is the amount of attention that the public, and especially the press, paid to her first large-scale exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1976. The debate that ensued brought unprecedented attention to her work, as well as to the larger world of contemporary art, the role of governmental funding, and its relationship to the viewing public.

Given its notoriety and importance, Kelly’s work in the ICA exhibition Post-Partum Document is a logical starting point for an investigation into the London art world and the impact of feminism in this period. In particular, Post-Partum Document helps to identify the central debates and key concerns of 1970s feminist artists, such as the representation of the female body, the use of everyday materials, conceptual and documentary strategies, as well as an interest in feminist politics and psychoanalytic theory.

This book attempts to situate Kelly’s work in the feminist debate around the body and to establish a wider context for Kelly’s practice. Catherine Elwes remarks that it is important to “think about the wider implications of what Kelly represented and how she fitted into the general pattern of what was going on and what people were saying and feeling and thinking about the body. And how she was part of the division.”3 Elwes refers to the dichotomy between women who used their bodies in their practice and those who did not. Elwes, whose use of her own body will be discussed in a later chapter, reminds us that Kelly’s resistance to depicting her body represents a decision taken by some feminists to use textual theory over visual form.4 Other women artists such as Elwes, Carolee Schneemann (in some works) and Cosey Fanni Tutti adopted the opposite strategy.

Post-Partum Document embodies traces of the body—both of the mother and the child—in its material. It does not, however, explicitly depict the body of either the artist or her child. Again, one can consider this strategy in relation to Judy Clark’s work of the same period, which also incorporated traces from the body, in this case that of the artist and her lover. Both Kelly and Clark used the serial form, reflecting the influence of both avant-garde film production and conceptual strategies. Finally, Kelly’s and Clark’s works will be considered alongside the work of Carolee Schneemann, whose provocative work during her stay in London made overt use of the nude female body. It is not my intention to provide a comprehensive re-reading of Kelly’s work, but rather to examine it in the context of other practitioners in London during this period.

THE ART OF EVERYDAY LIVING:

DOMESTIC MATERIALS AND TRACES OF THE BODY

An important hurdle that feminist artists in London faced was the lack of spaces that were willing to host exhibitions of their work. The opportunity for a feminist artist5 to show in the ICA, or any major art gallery, was not typical.6 Kelly’s exhibition came about through her affiliation with the ICA’s Director of Exhibitions, Barry Barker, who she met through her partner Ray Barrie.7 Barker was a member of the Artists Union.8 Kelly remained active in the Union longer than Barker, but the latter kept abreast of the progress of her work. When he was made Director of Exhibitions9 at the ICA he offered her a show, which was part of his curatorial policy of showing younger British artists in an international context. Kelly became one of a prestigious list of exhibitors that included Marcel Broodthaers, Lawrence Weiner, Dan Graham, Daniel Buren, Richard Hamilton and Dieter Roth, all members of an international avant-garde that Barker associated with, and was responsible for bringing to England at the time.

The ICA exhibition consisted of three parts of Post-Partum Document, a series-based work that documents Kelly’s son’s development from infancy into language.10 This included the sections titled “Documentations I–III” and a copy of Kelly’s introductory notes. Located in a simple grey binder these notes11 offer the viewer assistance in reading the piece and understanding the various diagrams. The notes, like the larger work, are divided into sections, and hence only four parts existed at the time of her show at the ICA. (Kelly would in subsequent years create three additional Documentations, numbers IV–VI.) Each section comprises a series of units, hung in Perspex boxes in the gallery. In total there would be 135 individual units in Post-Partum Document by the end of its gestation.

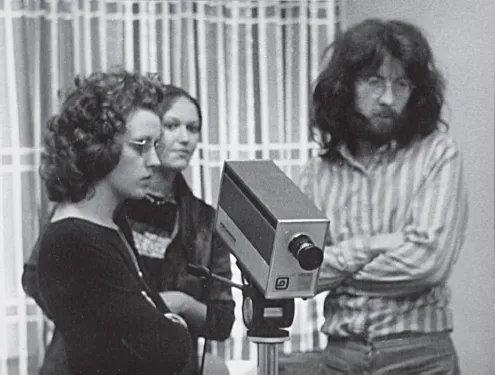

Figure 1.1

Mary Kelly (center) teaching at the London College of Furniture. Courtesy Mary Kelly Archive.

While Post-Partum Document is not about the physical manifestation of the mother’s form, parts of it clearly represent internal economies between mother and son, such as feeding, digestion and defecation. Writers such as Winnicott have remarked on the mother/baby unit; that is, during the breastfeeding months the traces of the baby’s faeces are traces of the mother’s milk, which is in turn a result of her diet. During the time of Kelly’s preparation of “Documentation I” Kelly12 was no longer breastfeeding, but the stains cannot be seen as simply an autonomous trace of the baby. They are also traces of the care provided by the mother, in this case, the artist.

Figure 1.2

(left) Kelly washing nappy liner, 1973; (right) Stained nappyliner drying, 1973. Courtesy Mary Kelly Archive.

“Documentation I: Analyzed fecal stains and feeding charts” is a section of Post-Partum Document that encompasses two elements important for this chapter: first, it is an example of Kelly’s decision not to depict her own body; and second, it caused a furore when exhibited at the ICA. The section opens with a chart (as each section does) that documents the body weight of the child over the course of twelve months. The look is quasi-scientific or medical.13 The scientific appearance of the graph, however, was not what the public14 objected to when the work was exhibited. Instead it was the twenty-eight other units in this series.

The nappy section (as it has come to be known) of the first documentation contains one unit for every day of the baby’s infancy in his sixth month, during February 1974. These were made from liners, which were washed by the artist, and left to dry, with stains intact. Kelly, who had recorded the child’s food intake for three months, would decide to use the period of February because it illustrated the most drastic change. During this interval the artist, like most new mothers in England in the 1970s, diligently noted every morsel that the baby ate and drank and these feeding charts provide the basis for the text that is typed on the dried liners. In the lower half of each liner is the daily intake, including feeding times and type of food. A total at the bottom of each liner provides a breakdown of the amount of solids and liquids that the child has consumed.

Figure 1.3

(left) diagram of infant metabolism 1974; (right) Post-Partum Document: “Documentation I: Analyzed fecal stains and feeding charts”, 1974. Courtesy Mary Kelly Archive.

Additional text is located at the bottom of each nappy. In the left corner the date is repeated in abbreviated form. The lower-right corner contains a numeral, either 01, 02, 03, 04. These numbers correspond to the artist’s classification of the child’s faeces as constipated, normal, not homogenous, diarrhoeal.15

While the notion of classifying faeces may have seemed absurd to a contemporary and largely male art audience, for a new mother at that time this would have been familiar territory. Classic child-rearing books, such as the popular Dr Spock’s Baby and Child Care, which Kelly owned and has a copy of in her archive, used faeces as an indicator of the child’s normality and health. In Benjamin Spock’s book science met popular culture as he proposed a hands-on approach to caring for the child. It was a huge success, with almost every mother owning a copy of his bestselling book.16 While at a primary level the mother’s insecurities about her child’s health can be alleviated with this book, Spock’s position was progressive. He opened up a generation of empowered parenting, by giving parents choices and encouraging them to use their own instincts in raising children.17

For Spock, and for the mother, the stains on the nappy liners are the visual and undisputable traces of the mother’s care of the child. In Kelly’s “Documentation I” she transforms the faeces stains into art. As the month of February progresses, and the child’s intake increases, the stains increase in size. This correlates with the growth of the child. Kelly has mentioned that in creating Post-Partum Document she was illustrating the lopsided division of labor within the family structure, where typically it is the woman who is responsible for the care and upbringing of the child. Here she illustrates that labor by documenting the daily duties of the mother, without actually presenting an image of her body. The schedule of feedings, combined with the fecal results, is an index, and hence non-figurative depiction, of this effort.

Figure 1.4

Original handwritten feeding charts, 1974. Courtesy Mary Kelly Archive.

Kelly spoke to Douglas Crimp about her reluctance to depict her own body in the work:

Kelly: In the mid 1970s, a number of women used their own bodies or images to raise questions about gender, but it was not that effective, in part because this was what women in art were expected to do. Men were artists; women were performers. … I wanted to question those essential places. … For instance I decided to use the vests in the Introduction because I couldn’t really “figure” the woman in a way that would get across what was going on, the level of fantasy that was involved, in an iconic way. I needed something that was more indexical, more like a trace.18

It was through Kelly’s close friendship with Laura Mulvey and the understanding that they developed, through the study of psychoanalysis, of voyeurism and fetishism,19 that the strategy of replacing her body with a trace in order to effect a critical distance emerged.20

DEPICTING EMOTIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES

“Documentation III” may also be considered here with regard to Kelly’s strategy toward the body. This section contains one introductory diagram followed by ten units of sugar paper mounted on white card, and the concluding Experimentum Mentis. Each of the ten “visual” units represents a chart, which is roughly divided into three sections. Reading the work from left to right, the ...